Charged for Growth: Electric Mobility Planning in San Jose, CA, 2020

20 minutes Author: Shared-Use Mobility Center Date Launched/Enacted: Feb 20, 2020 Date Published: February 27, 2020

This case study on San Jose is part of a collaboration between SUMC and the Hewlett Foundation that aims to explore a broad array of electric and shared mobility pilot projects across the U.S. and to build greater understanding of these innovative projects across various disciplines.

Brief Summary

- In 2018, the State of California set a goal of becoming carbon neutral by 2045. To achieve this goal, Governor Jerry Brown set aside $2.5 billion to install 250,000 electric vehicle charges by 2025 and get 5 million zero-emission vehicles registered by 2030.

- San Jose has looked to lead with integrating electric vehicles (EVs) into its transportation network. As of January 2020, San Jose had 50 public charging stations. Through the City’s Clean Air Vehicle Program, people can park EVs for free at all on-street parking meters and drive EVs in carpool lanes. The City is also facilitating the installation of EV charging stations at residential buildings.

- The City of San Jose is using its 2018 climate action plan, Climate Smart San José, and subsequent planning efforts to bolster the use of EVs.

Introduction

This case study first looks at the need for reducing transportation-related GHG emissions and then how the efforts of California have been implemented by San Jose at a local scale. San Jose’s efforts to increase local EV infrastructure and ownership were chosen to be featured in a case study because San Jose serves as an example for a comprehensive city-level approach. Additionally, SUMC worked with the City to develop its plan for installing EV-charging infrastructure, providing SUMC with first-hand details on the City’s initiatives. Insights were largely drawn from city-released publications, as well as interviews with representatives of the San Jose Department of Transportation.

The Need for Shared and Electric Strategies

In order to limit the potentially catastrophic impacts of climate change, the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) notes in its Special Report on Global Warming that carbon emissions must be reduced by 45% from 2010 levels by 2030.[i] Worldwide, the transportation sector is the fastest growing contributor to climate change, and it is now the single-largest source of emissions in the US.[ii] The majority of such emissions come from light-duty, gas-powered vehicle travel.

Given that the US is the third largest automobile market and the second largest producer of greenhouse gas emissions, there is a pressing need to shift the way American drivers think about their travel if the world is to meet global-emission reduction goals. In its most recent Assessment Report, IPCC reiterate the four primary mechanisms to mitigate greenhouse gas emissions in ground transportation:

Behavior changes:

- Reducing travel activity in motorized vehicles, increasing transit-oriented development, and densification

- Increasing mode share in efficient forms of travel, like public transportation and high-occupancy vehicles

Technology changes:

- Improving the energy efficiency of vehicles

- Switching vehicle fuels to low-carbon and renewable sources.[iii]

To have the greatest impact, electrification must accompany efforts to reduce passenger miles traveled and a paradigm shift to a more resource efficient transportation system that moves more people with fewer motorized trips.

What are Electric Vehicles?

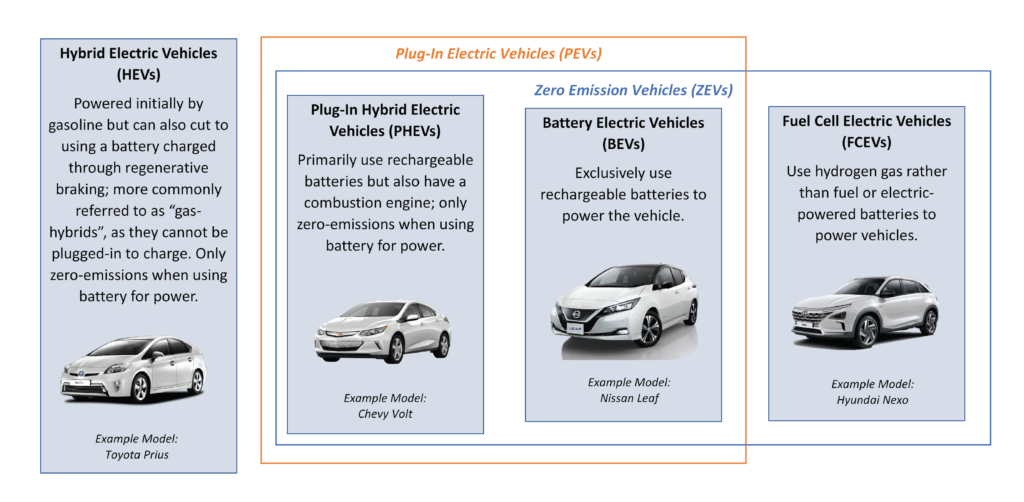

The category includes battery electric vehicles (BEVs) that exclusively use rechargeable batteries for power, plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) that primarily use rechargeable batteries but also have a combustion engine, and hybrid electric vehicles (HEVs) that are powered initially by gasoline but can also cut to using a battery charged through regenerative braking. BEVs and PHEVs are often referred to as plug-in electric vehicles (PEVs), whereas HEVs are more commonly referred to as “gas-hybrids”, as they cannot be plugged-in to charge.

Many efforts to shift drivers away from fuel-powered engines also include discussion of fuel cell electric vehicles (FCEVs), which use hydrogen gas rather than fuel or electric-powered batteries to power vehicles. Like BEVs, FCEVs do not have any tailpipe emissions. As a result, resources often refer to BEVs and FCEVs together as zero-emission vehicles (ZEVs).

According to the US Environmental Protection Agency, a typical gas-powered passenger vehicle emits about 4.6 metric tons of carbon dioxide per year, and that every gallon of gasoline burned creates about 8,887 grams of CO2.[iv] When operating using just the electric battery, EVs do not release tailpipe emissions, making their widespread adoption in place of fuel-burning engines a key component in achieving emission reduction goals.

California’s State-Level Leadership

Although the U.S. does offer incentives in the form of tax credits for purchases of EVs, it has not formally established any nationwide goals regarding EV adoption or infrastructure. In addition, the U.S. has chosen to withdraw from the Paris Climate Accords, a 2015 non-binding unified commitment to create national policies and plans to establish GHG emissions targets. Despite the absence of federal leadership, states and cities around the country have taken it upon themselves to develop more localized plans to reduce transportation-related emissions and accelerate EV adoption. Specifically, California has been a leader in state-level initiatives to combat climate change, particularly regarding transportation emissions.

Largely regarded as the birthplace of the American car culture, California was home to some of the worst urban air pollution in the country and began regulating auto-emissions as early as the 1950s. To accommodate the state’s aggressive action to fight pollution, the Clean Air Act of 1970 included an amendment requiring the US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to allow California to set stricter air quality standards. In 1990, the California Air Resources Board (CARB) instituted a Zero Emission Vehicle (ZEV) mandate requiring major automakers to either produce ZEVs, or compensate other automakers, in proportion with the number of vehicles sold in the state–the nation’s largest automobile market and the world’s eighth largest economy. The regulation was adopted by other states (Connecticut, Maine, Maryland, Oregon, New Jersey, New York, Rhode Island, and Vermont) and is credited with creating the modern electric vehicle industry, spurring widespread investments in battery technology, increasing the number of ZEVs and promoting efficiencies in gas vehicles.

In 2006, California instituted the first and still only carbon cap and trade program. Assembly Bill 32 gave CARB authority to regulate emissions and set a GHG reduction target of 1990 levels by the year 2020. Since the landmark bill, the state has passed a variety of appropriations and mandates to holistically tackle auto emissions. For example, in 2008, the California State Legislature passed Senate Bill 375, which requires the state’s 18 metropolitan planning organizations, covering 80% of the state’s population, to draft Sustainable Community Strategies that make plans for reducing GHGs through housing and transportation plans. In 2012, the State Senate passed Bill 535 requiring a certain amount of cap and trade revenue to provide funding for clean transportation projects in disadvantaged communities (DACs) identified by the California Environmental Protection Agency (CalEPA) as being overburdened by pollution and historic underinvestment.

However, California’s most significant step in combating climate change – and subsequently, in advancing EV adoption – came in 2018 when Governor Brown signed an executive order setting a goal of a state-wide carbon neutral economy by 2045. The state aims to reduce both greenhouse gas emissions by 40% below 1990 levels and petroleum use by 50% by 2030. To achieve this, Governor Brown allocated $2.5 billion to get five million zero-emission vehicles registered in the state by 2030 and to install 250,000 EV chargers by 2025.[v]

Pursuant to this executive order, the California Public Utility Commission (CPUC) established the Low Carbon Fuel Standard, which is a program that allocates credits and deficits to providers of transportation fuels, and some electric and natural gas providers in the state are able to sell their credits to provide rebates to customers with EVs. The CPUC is also working collaboratively with CEC, CARB, and CAISO on a vehicle-grid integration (VGI) initiative, which aims to better align EV charging with the needs of the electric grid.[v]

California will also receive significant funding as a result of the settlement with Volkswagen Group for their diesel-emissions cheating scandal. As part of this settlement, Volkswagen was required to pay $800 million to California and $1.2 billion across the rest of the US over ten years, and states can use their allocations for public EV infrastructure (up to 15% of allocated funds) and access.

These initiatives – and specifically, these funds – are critical to moving the needle on EV adoption rates. As a result of these concerted efforts, California has the largest share of EV market in the country, with 7.84% of new light-duty vehicles sold in the state being EVs in 2018.[vii] San Jose has benefited from many of these programs at the city-level.

A City-Level Approach: San Jose

In addition to California’s ambitious emission-reduction policies and initiatives, many cities across the state are pursuing even more localized plans to address transportation-related climate change. With one of the highest rates of EV adoption in the country, San Jose offers an example of a comprehensive city-level approach to mitigating transportation emissions.

San Jose’s Current Status

As of January 2020, San Jose boasts over 50 public charging stations, most of which are accessible at public parking garages in the downtown area. In addition, the City’s Clean Air Vehicle Program permits parking for free at all City on-street parking meters, and it encourages EV ownership by permitting use of carpool lanes for drivers with Clean Air Vehicle decals.[viii] San Jose has also successfully streamlined the process to better facilitate installation of EV charging systems in residential buildings.

In 2017, 12% of San Jose’s new vehicle sales were electric vehicles, which was well above the California-wide rate of 7.84% in 2018,[ix] and significantly above the US-wide rate of 2.1%.[x] Nevertheless, in order to meet the City’s emission reduction goals, such progress is not sufficient. San Jose calculates that as of October 2018, EVs comprised just 3% of all registered vehicles in the City, and that number drops to just 0.6% if considering only fully-electric vehicles. To achieve GHG emission levels aligned with Paris Climate Accords, San Jose will need over three times as many EVs registered on its roads by 2025, and nearly 13 times as many by 2040.[xi] San Jose’s multi-pronged efforts to increase EV adoption in both public and private spaces aim to tackle this challenge.

Overview of City Efforts to Increase EV & Shared Mobility

Timeline of Select San Jose Plans that Address Transportation Emissions

San Jose EV & Shared Mobility Efforts

In October 2007, San Jose adopted its Green Vision plan, a 15-year sustainability plan. Green Vision featured 10 goals for the city, all oriented around economic growth and GHG emission reductions.

A decade later, however, the City determined that it needed a more focused plan to better guide its direction. In 2018, San Jose replaced Green Vision with Climate Smart San José (Climate Smart), the City’s Paris Accord-aligned climate action plan. The plan is oriented around nine detailed strategies, including transitioning to a renewable energy future, creating clean, personalized mobility choices, and developing integrated, accessible public transit infrastructure. Specifically, Climate Smart set a transportation emission reduction target of 90% by 2050 and a goal of 63,099 electric vehicles registered in the City by 2025.

Much like the Paris Climate Accords themselves, Climate Smart is a long-term plan, with a focus on mitigating emissions over the coming decades. However, San Jose also recognized the need to take immediate steps to increase EV adoption in the short-term, as well as to plan for the long-term. As a result, the City developed its “San Jose Electric Mobility Roadmap: 2020-2022” (Roadmap), which is a short-term strategic plan aimed specifically at helping the city achieve the broader goals delineated in Climate Smart San Jose. This Roadmap was adopted by the City Council in January 2020.

Going forward, the City will also begin developing its comprehensive Emerging Mobility Action Plan in early 2020, which will be a five-year plan that will lay out the strategies to be employed to achieve the city’s sustainable transportation goals relating to electrification, automation and shared mobility.

Climate Smart San Jose

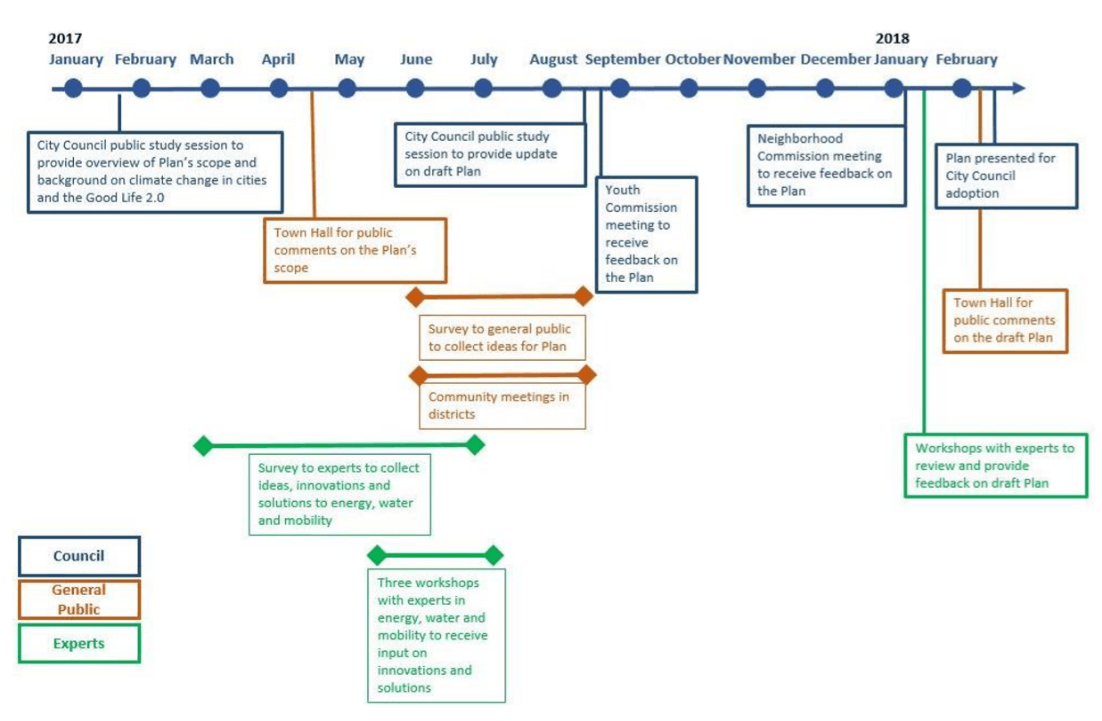

Climate Smart was adopted City Council in February 2018, and it serves as one of the country’s first city-level plans featuring targets aligned with the Paris Climate Accords. Momentum for Climate Smart largely began with a memo released by the City’s Mayor in 2016 which called for a new plan to refocus the existing Green Vision plan into a workplan to address three priority areas: energy, mobility & water. The city also allocated funds from its general 2016-2017 operating budget in order to develop a Request for Proposal and hire consultants to develop this new plan. The city contracted with consultants PricewaterhouseCoopers for $250,000 in December 2016 (with an additional $325,000 the following year), and it was able to leverage a $1.25 million award from the Pacific Gas & Electric Company for sustainability programs toward the cost of the development of Climate Smart.

The final plan was developed by the San Jose Environmental Services Department with input from national and local non-profits like the League of Women Voters of San Jose/Santa Clara and the Natural Resources Defense Council, the plan set mid-century targets for air pollution, water and energy conservation efforts in nine areas. Experts were also consulted through surveys and workshops throughout the development process.

For transportation, Climate Smart outlined two approaches, echoing the four mechanisms of mitigation identified by the IPCC:

- Behavior: Reducing the need to drive alone by expanding other mobility options, including building more housing near transit nodes, improving bike and pedestrian facilities, and expanding public transit, shared bikes and scooter services.

- Technology: Accelerating the adoption of electric vehicles for trips that require a car, SUV or truck. Climate Smart set a transportation emission reduction target of 90% by 2050 and 63,000 registered electric vehicles by 2025.

As a result of the aggressive goals and comprehensive strategic approach outlined in Climate Smart, the city received implementation support from the American Cities Climate Challenge.

Timeline of Development of Climate Smart San Jose

San Jose Electric Mobility Roadmap

While Climate Smart established San Jose’s long-term goals, the city recognized that achieving these goals also required articulating interim steps. The result was the Electric Mobility Roadmap (Roadmap), passed by the San Jose City Council in 2020. The Roadmap serves as an implementation guide through the year 2022, with the aim of helping the city achieve the broader goals delineated in Climate Smart. The Roadmap focused city actions around PEVs and Electric Vehicle Supply Equipment (EVSE), the industry term for electric charging stations and charging appliances.

In order to address Climate Smart’s transportation- and mobility-related goals, the Roadmap addresses three areas of impact: EV charging infrastructure, EV fleets, and personal and shared mobility services. For each area, it highlights the city’s ongoing efforts and proposes strategies for the city to further such efforts.

EV Charging Infrastructure: In order to assess how San Jose can best accelerate EV adoption rates through EV charging infrastructure, the Roadmap assessed the current distribution of EVs and EVSE in the city, and it determined where additional chargers would be best suited in order to expand access to EVs to residents across a wider income spectrum. One of the city’s ongoing initiatives highlighted by the Roadmap in this area is the city’s work with PG&E for 162 EV charger “ports” at five locations around the city, including the City Hall and local zoo. PG&E will cover the costs incurred in providing power to the charger clusters. One of the strategies the Roadmap recommends is for the city to review its Electric Vehicle Reach Code to assess if revisions are warranted, particularly by incorporating requirements to include property owners who make major renovations to their buildings.

EV Fleets: According to the Roadmap, targeting fleet vehicles could serve as a particularly effective strategy to reach established electric vehicle growth targets. The Roadmap recommends that the San Jose replace all non-police sedans that are more than ten years old to electric vehicles. Doing so would significantly reduce greenhouse gas emissions, as these vehicles account for more vehicle miles per year than the average passenger vehicle. Furthermore, such an initiative would demonstrate city-level leadership. The Roadmap also proposes that San Jose assess how the City’s expanding electric fleet could pose risks as well as create opportunities to boost the City’s resilience.

Registering Personal and Shared Mobility Devices: In regards to personal EV ownership, the Climate Smart plan established a goal of 63,099 electric vehicles in the City by 2025. Because one of the largest barriers to greater EV adoption rates is the cost to purchase them, the Roadmap suggests that the City help to establish a group buy or lease program. According to the Roadmap, such a program “would be particularly beneficial to lower-income families who own a car out of necessity, but bear a heavy financial burden to do so.” To increase offerings of shared mobility devices, the Roadmap highlights that the city is already expanding access to its e-scooter and bikeshare programs, and it suggests that San Jose encourage local carshare company, Zipcar, to incorporate EVs into its fleet.

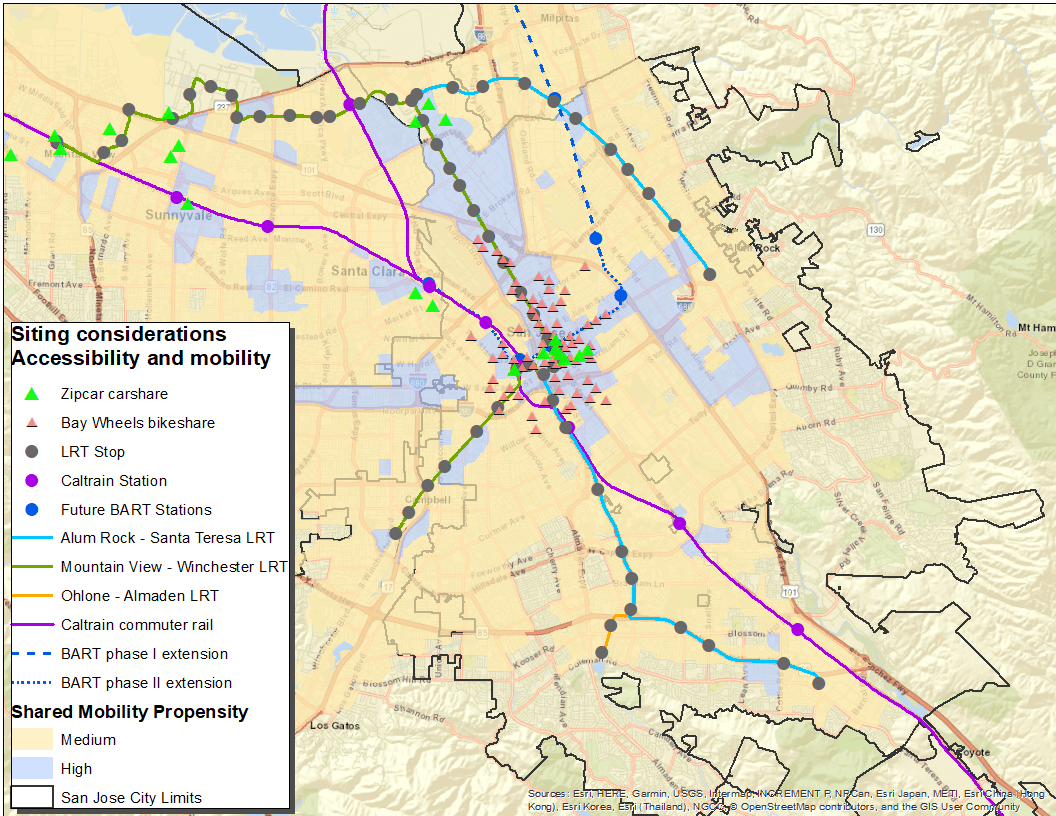

EVSE Implementation Planning

Pursuant to its effort to determine priority areas for new EVSE to expand access to EVs, San Jose worked with SUMC to develop a GIS mapping tool. This tool served to illustrate potential areas for EV infrastructure that would facilitate faster buildout. In any initiative to implement additional EVSE, planners must bear in mind the ‘chicken and egg’ dilemma: that existing demand for EVs is in part a function of existing conditions, and that potential demand can be stifled when strictly examining market conditions. Across the country, EV ownership is often higher among wealthy communities, in part because the market prioritizes placing new EVSE in such communities where use will likely be greater.

Credit: SUMC

However, in order to ensure increased access to EVs, new EVSE need to be considered in locations that may have been avoided by the private market due to cost or ease of implementation and will likely require greater public investment. As such, the GIS mapping tool was encouraged to emphasizes an intersectional approach to EVSE site locations that leverages partnerships and reaches the maximum number of people. Urban areas with large numbers of renters and unassigned parking were to be prioritized over suburban and heavily residential settings, particularly for fast-charging.

The resulting “gap” analysis showed that nearly 425,000 employees working at one of 45,000 employers in tracts with an identified charging gap. Additionally, the largest employers in the city and the region are in the public sector. The City of San Jose, Santa Clara County, San Jose United Schools, and San Jose State University have properties throughout the county including public parks (289), clinics (60), hospitals (22), city and town halls (2), community centers (42), court houses (12) libraries (38) and schools (700). On-site parking at these locations represent potentially streamlined opportunities for workplace-oriented charging and could be targeted for specific outreach. For EVSE catering to employees, AC Level 2 is most appropriate, while those with higher parking turnover could be suitable for DC Fast Charging. The Roadmap proposes establishing a regional, dedicated fund to pay for electrical upgrades and new chargers to keep pace with anticipated use in the coming years.

In addition to fostering increased vehicle ownership through accessible charging, the spatial analysis takes into account Climate Smart’s first goal of supporting active and high-occupancy transportation. SUMC maintains a tool that uses transit quality, pedestrian connectivity, household demographics and existing shared mobility to examine where the market could support additional shared mobility service with limited public-support. Between the range of publicly owned parking at public destinations, as well as the 2,678 on-street meters operated by San Jose, there is ample room to build out charging dedicated to services like electric-carshare. Shared mobility is most effective when viewed as part of the same service network as public transit.

Credit: SUMC

Conclusion and Takeaways from Other Cities and States

San Jose’s various efforts highlighted in this case study serve as an example for others aiming to reduce transportation-related emissions and create a more sustainable mobility system. The city has been able to leverage California’s ambitious state-level initiatives, while also charting its own course through both short- and long-term plans. Climate Smart set the city on a path to reduce transportation emissions over the coming years, while the Roadmap served as a more detailed workplan to help guide the City’s progress. Following the adoption of the Roadmap by San Jose City Council in January 2020, the city continues to look ahead. The Emerging Mobility Action Plan will be a five-year plan beginning in 2022, and because the Roadmap was not informed by an extensive community engagement effort, this next plan will heavily engage the community in its development process.

However, San Jose is not alone in its comprehensive approach to reducing transportation emissions. Other states and cities across the country are pursuing this goal as well. For example, in 2017, the governors of eight western states signed a Memorandum of Understanding to create an Intermountain West EV Corridor that will make it possible to drive an EV across major transportation corridors. The participating states plan to coordinate regarding EV charging station locations, creating voluntary minimum standards, and leveraging economies of scale.[xii] Similarly, eight states in the Midwest established the region’s first ZEV highway, while 11 states on the East Coast are exploring the adoption of EV corridors and transportation carbon markets.

Individual states have also been pursuing opportunities to incentivize EV adoption. Colorado, for instance, has a statewide EV plan to create a network of EV fast-chargers throughout the state. Delaware and New York both offer rebates to customers purchasing EVs, and New York’s Governor Cuomo has committed the state to increasing available public EV charging infrastructure fivefold between 2018 and 2021.[xiii] An executive order in North Carolina required the establishment of statewide ZEV plan with a goal of having 80,000 ZEVs on the road by 2025.

At the city level, Atlanta, GA passed legislation in November 2017 that requires 20% of parking spaces in new commercial and multifamily parking structures to accommodate EV charging, which includes equipping the spaces with conduits and sufficient electrical capacity to support EV charging infrastructure.[xiv] This is similar to the revised building code in Vermont which also requires EV-ready spaces for most new commercial and residential projects.

In addition to incentivizing the private the sector to build EV charging infrastructure, several cities are also undertaking the task of building the infrastructure themselves. New York City, NY, for example, has partnered with Commonwealth Edison to install 120 curbside Level 2 EV chargers across all five boroughs over the next four years.[xv] In the Midwest, Columbus, OH was able to leverage federal funds from the U.S. Department of Transportation’s first-ever Smart City Challenge to support its EV adoption goals. The resulting “Smart Columbus” initiative aims to increase EV market share to 1.8 percent by 2020 (from a baseline of 0.37 percent in 2015) and to deploy over 900 public EV charging ports.

Closer to San Jose, Los Angeles, CA has released a comprehensive plan for the City aimed at addressing climate change, with clear sustainable transportation goals and strategies for achieving them. In this “LA’s Green New Deal” report released by Mayor Garcetti in 2019, the city establishes the goal of having ZEV make up 100% of vehicles on the road by 2050, with all of public buses using EVs by 2030.[xvi] This plan was developed by building on the Sustainable City Plan introduced in 2015, which led to innovative programs like the BlueLA, the first EV carsharing program in the U.S. primarily intended to serve disadvantaged communities.

Internationally, many countries have committed to phasing out ICE vehicles, either through ceasing imports and purchases or banning use altogether. The list of countries with plans to prohibit new ICE vehicles from their roads by 2030 includes: Austria, Denmark, Costa Rica, Germany, India, Ireland, Israel, the Netherlands, Norway and Scotland. To achieve this goal, countries have established various incentive programs to help accelerate EV adoption rates nationally. Norway, for example, permits customers purchasing an EV to pay a reduced (or eliminated) import tax relative to fuel-powered vehicles, as well as a reduced annual road tax and value-added tax. Currently, the U.S. offers tax credits ranging up to $7,500 for the purchase or lease of qualifying new EVs, although such credits are phased out for each manufacturer after they have sold 200,000 qualified vehicles.

What all these examples illustrate is that there is a growing body of information and resources available to cities and states seeking to develop sustainable, equitable transportation systems that leverage emerging electric technology and related policies. San Jose’s efforts offer one city-level example of a comprehensive approach addressing both short- and long-term needs to reach ambitious transportation emission reduction goals.

Acknowledgements

This case study on San Jose is part of a collaboration between SUMC and the Hewlett Foundation that aims to explore a broad array of electric and shared mobility pilot projects across the U.S. and to build greater understanding of these innovative projects across various disciplines.

The series of case studies released through this collaboration serves to capture emerging best practices among mobility and charging operators and local governments and to highlight the successes and challenges faced through the projects’ lifecycle. A particular emphasis is placed on opportunities to scale the featured projects and bring them into the mainstream. The case studies largely rely on performance data, publicly available reports, and stakeholder interviews.

A special thank you to Laura Stuchinsky, Sustainability Officer–Transportation Department at City of San Jose for taking the time for an interview.

This case study was written by the Shared-Use Mobility Center.

References

[i] Interntional Panel on Climate Change. Summary for Policymakers of IPCC Special Report on Global Warming of 1.5°C approved by governments, October 8, 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/2018/10/08/summary-for-policymakers-of-ipcc-special-report-on-global-warming-of-1-5c-approved-by-governments/

[iii] Partnership on Sustainable, Low Carbon Transport (SLoCaT). ”Transport and Climate Change Global Status Report”, 2018. http://slocat.net/sites/default/files/slocat_transport-and-climate-change-2018-web.pdf, pp1.

[iii] Sims, Ralph & Schaeffer, Roberto. “Fifth Assessment Report, Chapter 8“, IPCC, 2018. https://www.ipcc.ch/site/assets/uploads/2018/02/ipcc_wg3_ar5_chapter8.pdf

[iv] United States Environmental Protection Agency. ”Fast Facts on Transportation Greenhouse Gas Emissions.” June 2018. https://www.epa.gov/greenvehicles/fast-facts-transportation-greenhouse-gas-emissions

[v] San Jose Electric Mobility Roadmap, 2020. https://sanjose.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=7965077&GUID=6055F811-99D3-4052-BF9E-6B999ABFF7D0

[vi] California Public Utilities Commission. Vehicle-Grid Integration Communications Protocol Working Group, 2020. https://www.cpuc.ca.gov/vgi/

[vii] National Association of Governors. “Transportation Electrification: States Rev Up”, September 15, 2019. https://www.nga.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/09/2019-09-15-NGA-White-Paper-Transportation-Electrification-States-Rev-Up.pdf

[viii] City of San Jose. ”Electric Vehicles,” San Jose Clean Energy, 2019. https://www.sanjosecleanenergy.org/ev

[ix] San Jose Electric Mobility Roadmap, 2020. https://sanjose.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=7965077&GUID=6055F811-99D3-4052-BF9E-6B999ABFF7D0

[x] Hertzke, Patrick, Müller, Nicolai, Schaufuss, Patrick, Schenk, Stephanie & Wu, Ting. “Expanding electric-vehicle adoption despite early growing pains,” McKinsey & Company, August 2019. https://www.mckinsey.com/industries/automotive-and-assembly/our-insights/expanding-electric-vehicle-adoption-despite-early-growing-pains

[xi] San Jose Electric Mobility Roadmap, 2020. https://sanjose.legistar.com/View.ashx?M=F&ID=7965077&GUID=6055F811-99D3-4052-BF9E-6B999ABFF7D0

[xii] National Association of State Energy Officials. “REV West”. https://www.naseo.org/issues/transportation/rev-west

[xiii] New York State Governor. “Governor Cuomo Announces $250 million Initiative to Expand Electric Vehicle Infrastructure Across New York State”, May 31, 2018. https://www.governor.ny.gov/news/governor-cuomo-announces-250-million-initiative-expand-electric-vehicle-infrastructure-across

[xiv] City of Atlanta, GA. ”Press Release: City of Atlanta Passes ’EV Ready’ Ordinance into Law”, November 21, 2017. https://www.atlantaga.gov/Home/Components/News/News/10258/1338?backlist=/

[xv] New York City Department of Transportation. Projects & Initiatives: Curbside Level 2 Electric Vehicle Charging, 2018. https://nycdotprojects.info/project/839/overview

[xvi] Los Angeles Mayor Garcetti. L.A.’s Green New Deal: Sustainable City Plan, 2019. http://plan.lamayor.org/sites/default/files/pLAn_2019_final.pdf