Pop-Up Mobility Paths & Open Streets due to COVID-19 Crisis

20 minutes Author: Shared-Use Mobility Center Date Launched/Enacted: May 13, 2020 Date Published: May 13, 2020

Brief Summary

- Since March 2020, public transit and transportation network company (TNC) ridership dropped dramatically worldwide due to COVID-19. On the other hand, the pandemic has increased the willingness to explore open streets and mobility paths.

- Cities worldwide have been able to leverage existing resources to designate temporary or widened bike lanes, divert traffic in certain areas, reallocate road space to cyclists and pedestrians, and implement traffic calming measures. In many instances, these “pop-up” alterations are made using signage and tape.

- Though the lasting effects of COVID-19 remain uncertain, some transportation experts anticipate that the pandemic might result in increased use of active transportation modes. These pop-up paths can help agencies monitor and plan for changing mobility needs.

Introduction

The crisis caused by the novel COVID-19 virus in the spring of 2020 has been wreaking havoc on traditional transportation patterns. Beginning in March, public transit ridership and TNC use dropped precipitously in cities around the globe, and there has been speculation as to whether some e-scooter companies will be able to survive the pandemic’s financial fallout.

However, one potentially-optimistic outcome of the crisis has been an increased willingness on the part of cities to explore open streets and mobility paths to tackle the outbreak and the challenges it has raised for residents.

For example, Bogota, Colombia was one of first to garner national attention for launching temporary bike lanes to help prevent the spread of COVID-19. On March 17th, Bogota opened 22km (13miles) of bike lanes overnight by repurposing car lanes, with plans to open 76km (47miles) in total throughout the crisis. These temporary lanes were able to be reconfigured quickly and without significant city investment.

Other cities are pursuing similar efforts. Berlin, Germany, for instance, has worked to expand existing bike lanes to make more space for the uptick in travelers using these active modes. Oakland, CA, meanwhile, has launched a “Slow Streets” program to slow vehicle speeds and ensure roads can be more safely shared with bikers and pedestrians, and Philadelphia, PA closed down vehicle access to a section of its Martin Luther King Jr. Drive altogether.

In part, these and other cities have been prioritizing mobility paths during the pandemic because many have turned to active modes like bikes and scooters to avoid crowded public transit, where the risks of transmitting the virus are perceived as higher due to closer proximity to other users. For example, the Office of New York City Mayor, Bill de Blasio, actively encouraged residents to “consider commuting to work via alternative modes of transportation, like biking or walking, if possible.” Additionally, because vehicle traffic has decreased so significantly as a result of more people working from home and limiting their recreational movements, there is less congestion on streets, making the temporary reallocation of car lanes to bike lanes less contentious. Cities have also recognized an increased need for public space during the crisis, because so many people have turned to biking and walking to get exercise while other options are closed.

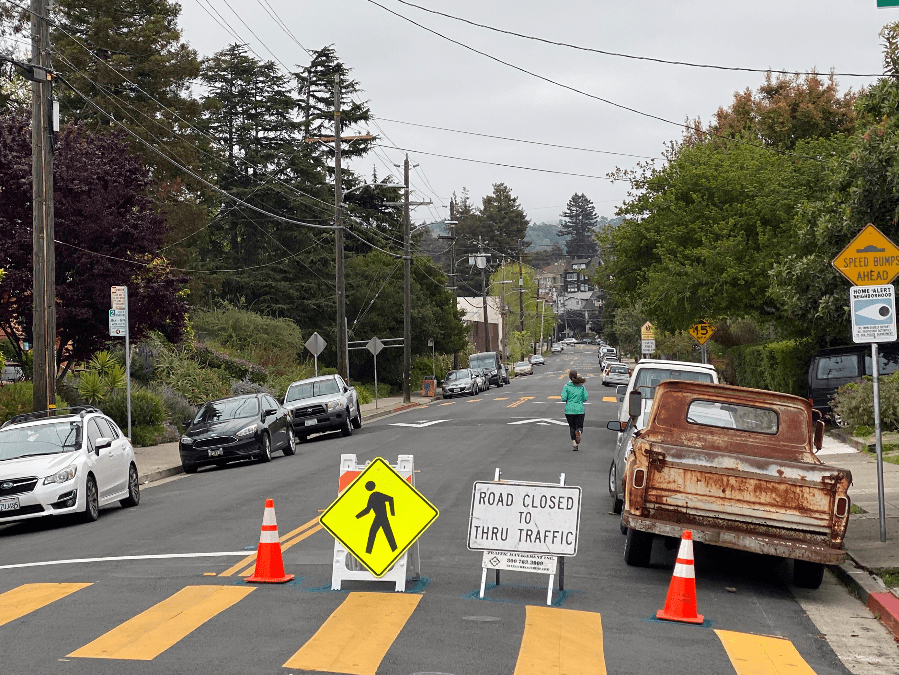

Because cities can use fairly cheap supplies like traffic cones, “Closed to Thru Traffic” signs and tape to denote these temporary mobility paths, they can be deployed quickly and without the large budget that accompanies major capital improvement projects like new bike lanes. However, much speculation abounds regarding what these efforts could mean for greater public support towards micromobility paths and pedestrian zones long-term.

Tools Leveraged

One of the reasons there has been a proliferation of mobility paths like expanded bike lanes and car-free zones during the COVID-19 crisis is because such paths can be established leveraging tools already at cities’ and transit agencies’ disposal.

In Berlin, for instance, the city used tape and mobile signs to denote its widened bike lanes. These tools can also be removed easily and the bike lanes returned to their previous size when travel patterns return to normal following the pandemic. Similarly, San Francisco, CA’s Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA) is using signs and cones to close select roads, divert traffic, and slow vehicles.

City cyclists have long advocated for the use of such inexpensive tools to facilitate safer biking where major investments like protected bike lanes are not feasible. This type of tactical urbanism has historically involved spray-painting potholes, placing cones to demarcate improvised protected lanes, and other DIY-traffic reducing actions. Cities can leverage the long-earned expertise of cycling and safe streets advocates for further similar endeavors.

City employee lays down tape for temporary bike lane, Berlin. Source: Annegret Hilse/Reuters

Community Engagement

In some instances, the push for temporarily reallocating space reserved for cars to cyclists and pedestrians came from residents themselves. In Philadelphia, PA, for instance, the order to close over 4 miles of Martin Luther King Jr. Drive to vehicles was largely due to a petition from non-profit Bicycle Coalition of Greater Philadelphia. Similarly, over 130 cities in Germany have seen petitions for more pop-up bike lanes, supported by environmental NGO Deutsche Umwelthilfe eV.

In other cases, cities themselves have taken the lead on deploying more mobility paths during the crisis. Oakland, CA’s Slow Streets program, for example, which aims to “make neighborhood streets safer to walk and bicycle during the COVID-19 shelter-in-place order” includes an interactive map for residents to suggest which streets should be included in the program, as well as a survey to gain greater feedback on preferences for existing and proposed changes. In Bogota, the city’s ambitious plan to deploy over 45 miles of temporary bike lanes coincided with a community awareness initiative to encourage use of active transportation modes and city-wide lockdown drills.

Map of proposed temporary bike lanes and existing system, Bogota. Source: Smart Cities.

Street Selection and Planning

For initiatives that close a corridor to vehicle traffic and open it to pedestrian and bicycle traffic, the street or streets selected are typically chosen because they are well-suited to help alleviate crowding, facilitate exercise and/or enable trips to meet essential needs. In Denver, CO, for example, the city asserted that it will prioritize deploying car-free zones in “densely populated neighborhoods and those without immediate park or trail access”. In a similar vein, the first 5 miles of expanded pedestrian space established in Minneapolis, MN as a result of COVID-19 were prioritized for areas where there were “higher concentrations of pedestrians accessing essential services and narrow sidewalks that do not easily support social distancing”.

Map of street closures, Minneapolis. Source: Minneapolis Public Works.

In San Francisco, CA, the city has launched Phase 1 of its Slow Streets program, with 12 corridors selected for participation. These streets were chosen to supplement reduced bus service caused by the pandemic, and the majority run parallel to major streets and transit routes in the area. The SFMTA asserts that the speed of the roll-out will depend on staff resources, with a goal of deploying about 2-3 corridors per week, at approximately 8 blocks at a time. Additional streets will also be selected that “prioritize walking and biking for essential trips”, and the city has launched a community survey to gain feedback on proposed corridors thus far. Burlington, VT’s Shared Streets for Social Distancing program has designated some corridors as “shared streets”, where vehicles should be driven slowly and drivers should be extra cautious, and other corridors as “local traffic only” streets, meaning the street should only be used for driving to destinations on that street. Some of the factors that contributed to corridor selection in Burlington included sidewalk availability, traffic volumes and neighborhood density and activity.

Initiatives to expand micrombility paths without prohibiting vehicle through traffic altogether also aim to increase mobility by facilitating more bike and scooter users. For example, Berlin’s effort to expand its bike lanes began in the neighborhood of Kreuzberg, where vehicle traffic was down significantly, and biking was already a commonly-used mode. In March, the city experimented by widening two busy bike lanes, and after determining that car traffic was not negatively impacted, it decided to expand the initiative to other lanes in the same neighborhood and to two other bike-friendly neighborhoods in April.

Widened bike lane in Berlin. Source: Philip Oltermann/The Guardian

Funding

While most cities have been able to reallocate space traditionally dedicated to vehicles to active transportation modes with resources already available – such as traffic codes, signage, and tape – some agencies are taking steps to provide financial resources to support this aim.

At the federal level, the New Zealand Transport Agency invited cities to bid for funding from its Innovating Streets for People fund to widen sidewalks and deploy temporary cycleways, and it lifted the budget cap on this fund. Similarly, the United Kingdom’s Department for Transport has announced that pop-up bike lanes with cycle and bus-only corridors will begin being established in the coming weeks by leveraging a £250 million emergency active travel fund, part of the £5 billion in funding for cycling and buses announced in February.

At the local level, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board passed a resolution in early May that authorized up to $250,000 to establish and maintain parkway closures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Long-Term Impacts

Although much remains uncertain about the long-term effects of the COVID crisis, many transportation experts anticipate that the pandemic could result in a sustained uptick in the use of active transportation modes like biking, e-scootering and walking.

Around the globe, cities experienced an increase in people turning to these modes during the pandemic, as they tried to avoid crowded public transit, navigate disruptions to their regular service, and keep healthy. Importantly, early data suggests that these trends may extend past the pandemic: modelling from London’s transit authority recently suggested the city could see a “tenfold increase in distances cycled, and up to five times the amount of walking compared with pre-coronavirus levels” following the crisis.

As a result, some cities are considering how to plan for this increased demand for mobility paths and walkable routes. Milan, for example, announced in April its Strade Aperte plan, which will result in a total of 35km (22 miles) of temporary bike lanes, widened pavements, and low speed limits to be deployed over the summer 2020. Paris, too, plans to invest heavily in expanding its existing bike lane systems after the city begins to open. In the US, long after stay-at-home orders are lifted, some cities may choose to experiment with keeping their street closures or pop-up bike lanes in place, at least on designated days or during select times. Barcelona’s “Super Block” program – which groups several adjacent blocks together, and through which traffic by vehicle is restricted or prohibited – could serve as an even more ambitious model for cities exploring long-term avenues to re-prioritize individual travelers over vehicles.

In general, active transportation advocates are hopeful that the pandemic – as disruptive and difficult as it has been – will at least spur support for more infrastructure that facilitates walking and micromoblity modes. From the cities’ perspective, experience with these sorts of pop-up lanes and shared street initiatives could be beneficial down the line, particularly if cities are faced with similarly disruptive events that require rapid responses to changing mobility needs.

Select Examples

Street Closures to Vehicle Traffic

- Philadelphia, PA: Closed 4.7 miles of Martin Luther King Jr Drive, following petition from a biking coalition

- Minneapolis, MN: Closed part of its riverfront parkways to motor vehicles; Park and Recreation Board passed a resolution in early May 2020 that authorized up to $250,000 for parkway closures

- Denver, CO: Closed roads around lake to help with social distancing while exercising

- Oakland, CA: Slow Streets Program

- San Francisco, CA: Slow Streets Program

- Burlington, VT: Shared Streets for Social Distancing Program

Pop-Up and Expanded Bike Lanes

- Bogota, Colombia: Opened 22km (13miles) of bike lanes overnight by repurposing car lanes, with plans to open 76km (47miles) in total throughout the crisis

- Budapest, Hungary: Established temporary bicycle lanes for several key routes, with lanes created at the edges of multi-lane roads in each direction.

- Winnipeg, Canada: Expanded active transportation routes on nine streets from 8 a.m. to 8 p.m.

- Calgary, Canada: Reduced lanes on some roads to help walkers, cyclists keep their distance

- Berlin, Germany: Widened bike lanes in select neighborhoods to accommodate more active transportation users during crisis