Public Transit during COVID-19 and the Road to Recovery

20 minutes Author: Shared-Use Mobility Center Date Launched/Enacted: Jun 26, 2020 Date Published: June 26, 2020

As part of SUMC’s on-going efforts to chronicle and assess how cities and transportation sectors are impacted by the novel COVID-19 coronavirus, this case study explores how public transit agencies in particular have addressed the unique challenges posed by the pandemic, and it highlights how they are preparing for a resurgence of riders as lockdowns begin to lift around the globe.

Brief Summary

- As the number of COVID-19 cases increased during the pandemic, many cities and transit agencies actively encouraged people to opt for other forms of transportation besides public transit when possible to avoid close contact with others and to leave more space for those who have no other choice for travel.

- Often, hourly, low-paying jobs are located far from where the workers holding those jobs live, making commutes longer and active transportation less feasible. These trends are especially true during the COVID-19 pandemic, and public transit users in Spring 2020 were more likely to be poor, minority, and minimum-wage workers.

- Exposure to the virus on crowded buses and trains is a major concern for transit agencies, so cities have found ways to help mitigate risks as they reopen and encourage the public to resume riding. Some of these mitigation measures include requiring face masks, making adjustments to flexible and on-demand services, limiting the number of people allowed to enter major stations, and ramping up disinfection efforts.

- Long-term responses like establishing detailed pandemic emergency plans, expanding access to micromobilty systems, and working to alleviate spatial mismatch can ensure that agencies can successfully navigate similar challenges.

Introduction

At outset of the COVID-19 pandemic, many cities and transit agencies actively encouraged people to opt for other forms of transportation besides public transit when possible. The mayor of Buenos Aires, for example, encouraged residents to prioritize use of bikes to “avoid close contact with others and leave more space for those who have no other choice for travel,” and Bill de Blasio, Mayor of New York City, encouraged people to bike to work in a tweet prior to the city implementing a lockdown.

As the number of cases of the virus increased, so too did concerns about the potential for crowded buses and trains to increase spread of the disease. By March 2020, the prevalence of stay-at-home orders, furloughs and layoffs – as well as the real and perceived risks of traveling via public transit – resulted in a precipitous drop in ridership around the country. However, for many who still needed to travel to work and access critical services, the ability to rent a bicycle or drive a private vehicle instead of using public transit to commute was not an available option.

Who is still riding?

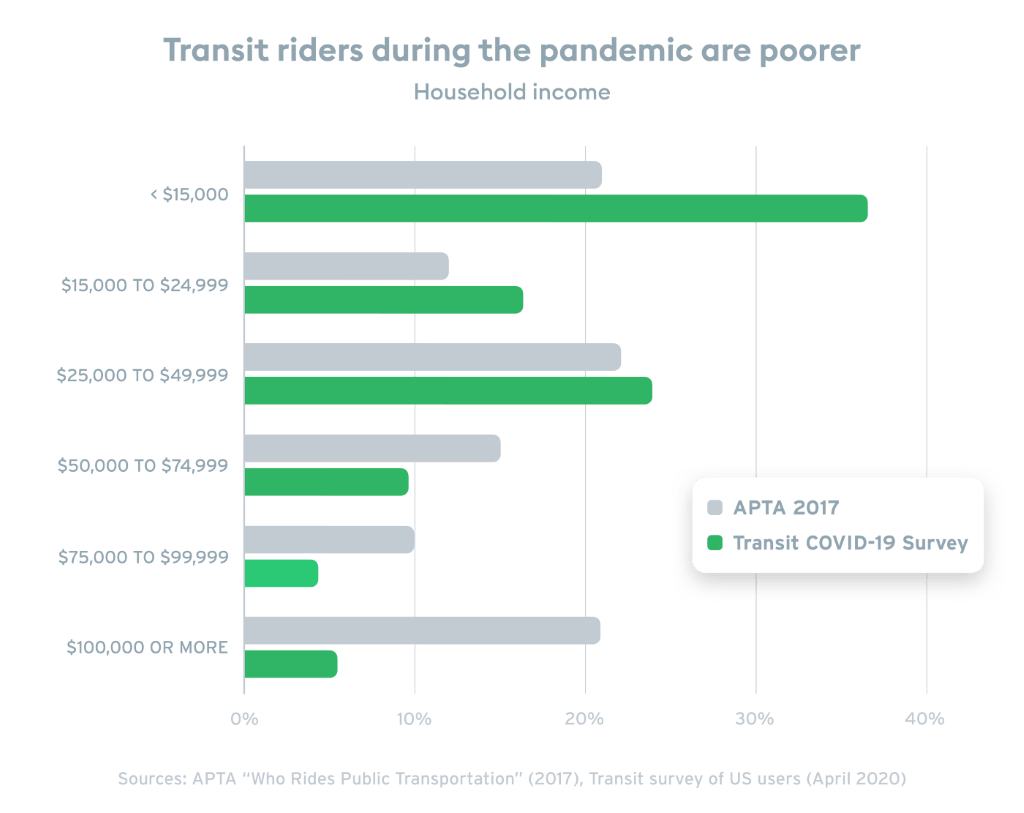

According to a survey of travelers using public transit in April 2020 conducted by Transit at the height of the pandemic in the US, more than 70% of those “essential workers” who continued to use public transit to commute during the pandemic make under $50,000 a year.

Often, hourly, minimum-wage jobs are located far from where the workers holding those jobs actually live, making commutes longer and use of active transportation alternatives like walking, biking or e-scootering less feasible. According to research published by the Urban Institute in 2019 using data from the US’s largest online marketplace for hourly jobs, there is a spatial mismatch in several major US cities between the number of job openings and the number of workers seeking those jobs who live within a reasonable distance (designated as 6.3 miles for the purposes of research). Such geographic discrepancy between where available hourly jobs are located and where people seeking those jobs live has been found to lead to higher unemployment rates.

In particular, this trend disproportionately affects minority populations, who are more likely to be working hourly jobs that cannot be done remotely, and who are more likely to live further away from employment clusters. In Chicago, for example, black low-wage workers spent about seven minutes more one-way on their commutes than white low-wage workers, according to 2011 data from the Census Bureau’s American Community Survey.

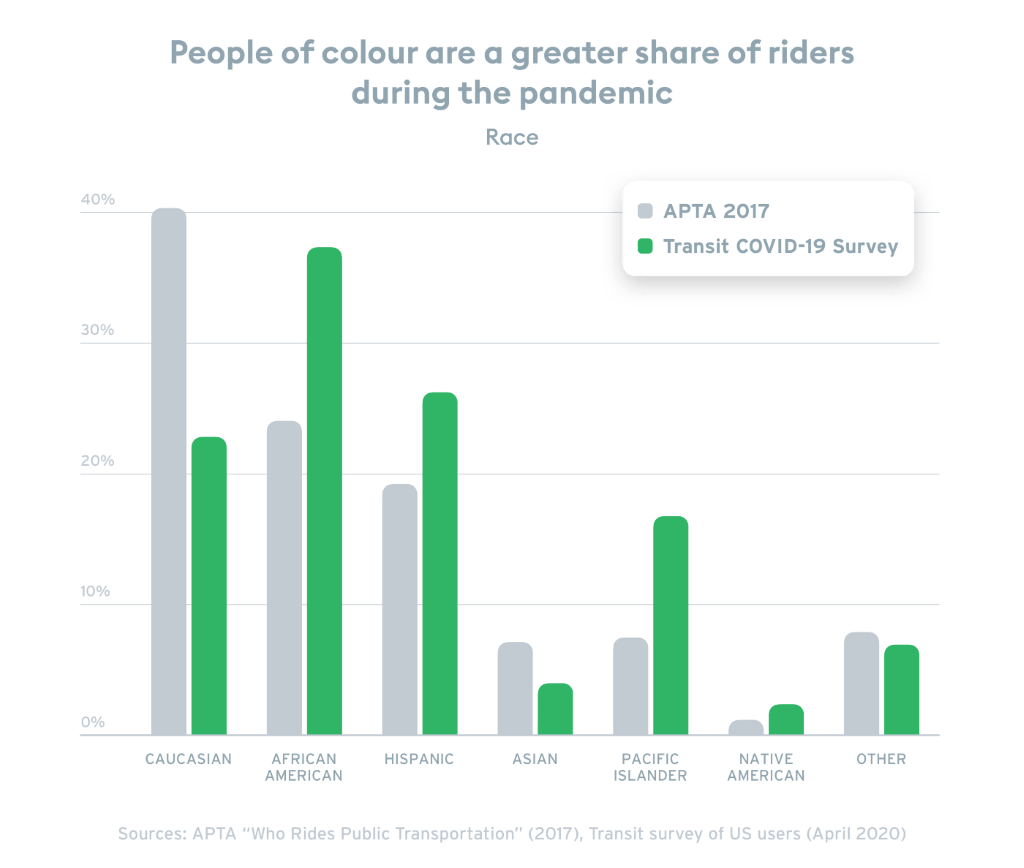

Often, these workers have the fewest mobility options, and therefore rely more heavily on public transit to reach their work and access other essential services. This is especially true during times of crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic: the people riding public transit in the spring of 2020 were more likely to be poor, minorities and minimum-wage workers. Transit’s survey of travelers using public transit in April 2020 also found that there had been a steep drop-off of white (and male) riders compared to the usual travel patterns, and most of those still riding were women and people of color.

Source: Transit COVID-19 Survey

Transmission on Public Transit

Much of the rhetoric surrounding use of public transit at the outset of the COVID-19 pandemic in March 2020 suggested that subways and buses were highly dangerous, and people should seek other transportation options to reduce their chances of exposure to the virus – particularly during peak travel times when vehicles and stations were likely to be at their most crowded. Many transit agencies in the US were discouraging people from riding transit for non-essential trips so that people could safely ride for essential trips, and even the CDC’s initial guidance (which was later revised) encouraged employers to offer incentives to employees to drive and park, rather than to use public transit – drawing the ire of organizations like APTA, NATCO and Transportation for America. However, for those individuals who continued to use public transit, how much higher was their risk of contracting COVID-19?

Common sense suggests that exposure to a virus is greater on a packed train than in a private car, or likely even on a shared bike. For example, one study from 2018 conducted at the Institute of Global Health found a correlation between regular use of the London Underground subway system and greater rates of flu-like symptoms. More specifically, people who had to take multiple lines or change trains had even higher rates than those who could reach their destination directly on a single line.

Early assumptions regarding public transit during the COVID-19 pandemic specifically reflected this concern. A report from an MIT economics professor released in April had suggested that New York’s busy subway system was “a major disseminator—if not the principal transmission vehicle” of COVID-19 in the city. However, that study has been heavily criticized and a look at other locations could suggest that public transit is not a primary means of transmission.

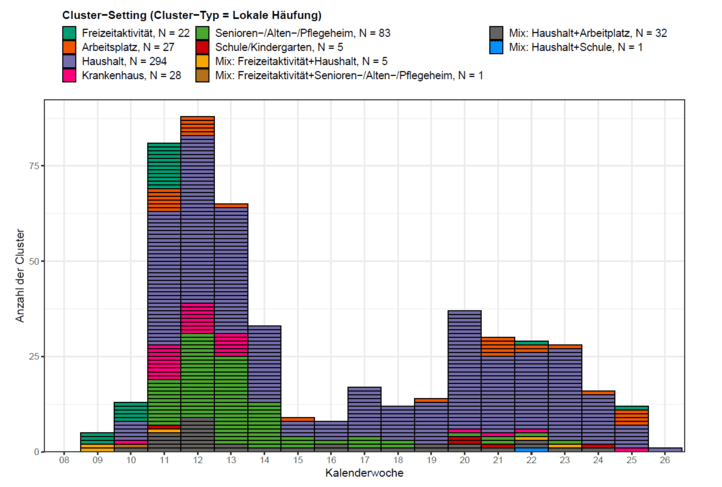

In Japan, for example, most clusters of the virus were determined to have originated in spaces where people were talking and interacting in close contact for extended periods of time, such as in gyms, pubs and live music venues. According to Hitoshi Oshitani, a virologist and public health expert at Tohoku University, no clusters were traced to crowded commuter trains in Japan, and transmission of the virus in such settings is assumed to have been fairly rare. In Europe, France also saw zero clusters associated with public transit, as did Austria.

Similarly, some assessments of transmission in China suggest that social distancing – especially on transportation vehicles – is not especially effective. Taipei, Taiwan also experienced some of the lowest rates of transmission in the world, despite also experiencing a much smaller drop-off of public transit use compared to most Western cities.

As the Atlantic asserted in June 2020:

“If transit itself were a global super-spreader, then a large outbreak would have been expected in dense Hong Kong, a city of 7.5 million people dependent on a public transportation system that, before the pandemic, was carrying 12.9 million people a day. Ridership there, according to the Post, fell considerably less than in other transit systems around the world. Yet Hong Kong has recorded only about 1,100 COVID-19 cases, one-tenth the number in Kansas, which has fewer than half as many people.”

Subsequent research will be required to determine just what the degree of risk was for transmission of COVID-19 on public transit, and if perceived concerns were over- or underestimated.

Mitigating Risks and Recouping Ridership

Already, there is concern that public transit will suffer long-term reputational damage as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, with some residents opting for what they consider to be safer transportation options, even as the crisis subsides.

Internationally

Optimistically, cities around the world have found ways to help mitigate risks of infection as they reopen and encourage residents to resume use of public transit. Some examples include:

- Requiring face masks on public transit, as was adopted nationally in Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, Hungary, and elsewhere in Europe as economies began to reopen. In Spain, police were tasked with handing out free masks to travelers in the first days after the lockdown was lifted. Many transit agencies individually in the US are also requiring that face masks be worn in stations and on vehicles, following federal recommendations.

- Making rapid adjustments to flexible and on-demand mobility services to respond to changing needs. In Germany, for example, Berlin’s BerlKönig on-demand microtransit program (operated by Via Vans but a component of the city’s public transit system) quickly adjusted the program’s service area to access 75% of hospital beds in the city, and it capped participating vehicles at 50% capacity.

- Placing clear markings at train stations to denote where to stand and avoid crowding, as was done throughout Italy. Rome also closed access to select stations when they grew too busy, and limited number of people allowed to enter major stations per hour.

- Ensuring sufficient coordination: In Madrid, the public company tasked with operating city buses and the bikesharing system formed a special coordination committee and adopted specific procedures early in the outbreak to better manage the pandemic response across multiple transportation modes; and

- Extending the length of time for seasonal transit passes to remain valid, as was done in Vienna for student passes that were not able to be used during lockdown.

In Taiwan, there were several aggressive, rapid steps taken that led to one of the lowest rates of transmission in the globe. This is in spite of the fact that Taipei, in particular, experienced a smaller drop in public transit ridership relative to most major US and European markets. Some such steps to combat transmission on public transit included:

- Leveraging the lessons learned from the SARS outbreak by deploying fast detection and contact tracing systems already in place;

- Conducting required temperature checks on passengers on the Taiwan High Speed Rail (TSHR), Taiwan Railways Administration (TRA), highway coaches, metro systems, city buses, and domestic flights;

- Conducting free COVID-19 tests at the airport for people arriving, and then providing transportation home from the airport to limit use of public transit; and

- Engaging in consistent and technologically-modern follow-up methods to check on those who may have been exposed to the virus.

In the U.S.

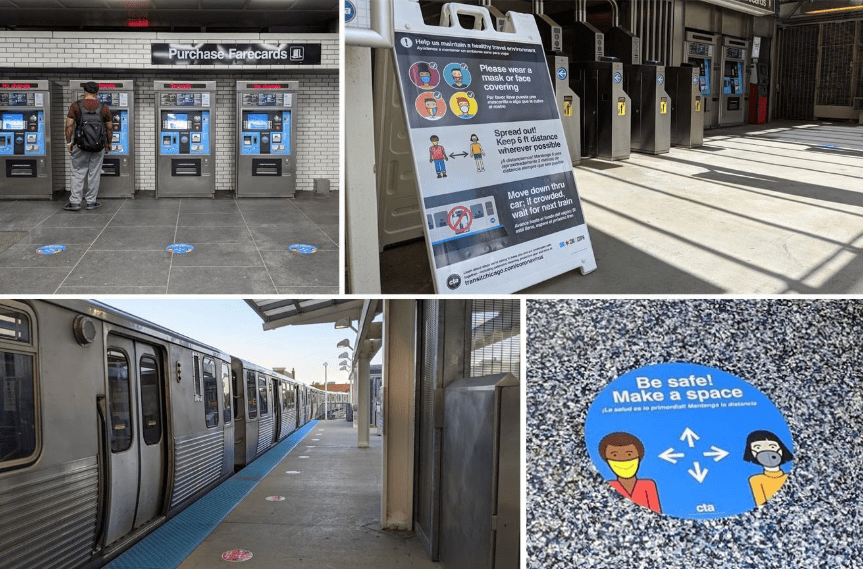

Several US public transit agencies have also taken steps to help reduce the risk of transmission. For example, the Detroit DOT hired more cleaning staff for its vehicles, and ramped up the frequency with which they were disinfected. In Chicago, transit workers were instructed to pay special attention to disinfecting areas that are touched most frequently by customers, such as turnstiles, handrails, escalator railings, seats, and ticket machines. In New York City, the MTA launched a $1 million pilot in partnership with Columbia University in May that uses mobile ultraviolet lights to disinfect buses and trains while service is shut down late at night.

In addition, specific attention has been paid to the risks faced by transit employees, and drivers in particular. For example, the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) has provided several resources to guide agencies’ response to the pandemic, with some recommendations including adopting rear-door boarding and temporarily suspending fares to better protect drivers from exposure to the virus from passengers. An Issue Brief released in June 2020 from Dream Corps Green For All suggests that, based on survey results, transit justice groups remain concerned about whether agencies can sufficiently enforce social distancing, if they will be able to provide enough protective equipment for drivers, and if they will recognize the need for hazard pay. Furthermore, the Issue Brief highlights stories of drivers lacking access to restrooms during their shifts due to the closure of public restrooms or taking on additional cleaning duties, and one union representative interviewed called for mandatory and specific requirements from the federal government to strengthen safety and labor protections for transit employees.

Credit: TriMet

US transit agencies are also beginning to consider ways to “reopen” safely as ridership rebounds in the coming months. These city-specific reopening plans consider operational components including vehicle and station cleaning, service changes and employee protections, many of which reflect the best practices emerging in Europe. Some such plans include:

- MTA Reopening Plan (NYC, NY)

- CTA Covid Measures (Chicago, IL)

- Muni Covid Reopen Plan (San Francisco, CA)

- TriMet Returning to Transit User Guidelines (Portland, OR)

A June 2020 report released by the Tri-State Transportation Campaign also recommended the follow procedures to limit crowding in the short-term: increase service frequency; alter station flow; reduce maximum occupancy limits; and modify schedules and institute incentivized fare structures, including discounts for off-peak use to incentivize riders to spread trips over the course of the day and avoid rush hour commutes. In the longer-term, the report encourages the deployment of app-based fare collection to reduce touchpoints, the installation cashless payments at bus doors, and the upgrade of ventilation systems.

Additional resources:

- NCHRP Report 769: “A Guide for Public Transportation Pandemic Planning and Response” from 2014 is designed to assist transportation organizations as they prepare for pandemics and other infectious diseases such as seasonal flu.

-

- A report summary updated in early 2020 specifically regarding COVID-19 is also available.

- FTA: “COVID-19 Resource Tool” which includes detailed guidance on vehicle and facility cleaning best practices, including using disinfecting products with at least 70% alcohol and cleaning “high touch surfaces” like kiosks and restroom surfaces at least once per day.

- JLL Report: “Public transit challenges in a post-pandemic world” from June 2020 that explores public transit use across markets, post-pandemic commute challenges, and potential solutions for the next normal.

- USDOT Pandemic Flu Planning homepage

- Dream Corps Issue Brief: Securing Safe Transit Before and After COVID-19

- APTA Recommended Industry Guidance: Cleaning and Disinfecting Guidance During a Contagious Virus Pandemic

Long-Term Takeaways

In addition to short-term responses to mitigate risk from viral outbreaks like COVID-19, cities and public transit agencies should also consider long-term avenues to meet the mobility needs of all residents in future similar crises. These investments will also help to alleviate overcrowding on public transit and mitigate the risks for those individuals that need to still use it during the height of a pandemic and moving forward.

For example, cities should establish a detailed pandemic emergency plan that can help guide their responses to future outbreaks and emergencies and ensure more rapid deployment of resources. These plans should address how to maintain or create routes transporting essential workers during crises. Such a plan could have alleviated some of the frustration experienced in Boston during the COVID-19 pandemic when the city’s transit agency initially changed its commuter rail timetables in a way that made it difficult for doctors, nurses and other medical staff to get to the area’s many healthcare centers in time for their early morning shifts. Plans should also explore ways to quickly leverage alternative transportation modes that are affordable and healthy, such as bikesharing and bicycling more generally. For more information on how cities are exploring pop-up bike lanes and pedestrian zones, see SUMC’s case study. Additionally, these agency-specific emergency plans should facilitate use of best practices learned from the COVID-19 experience; for example, they should establish the steps needed to enable an agency to quickly distribute face masks to employees and riders.

Cities should also expand access to bikeshare systems and invest in supporting infrastructure to make biking and scootering a feasible mobility option for all. New York City has already announced an expansion of its public Citi Bike system into upper Manhattan and the Bronx in 2020, as well as plans for ten additional miles of bike lanes in both Manhattan and Brooklyn. By increasing access to micromobility modes such as bikeshare now, residents will have more options available to them should similar crises breakout in subsequent years.

Divvy bikes at docking station, Chicago

In addition, cities and transit agencies can help to alleviate the spatial mismatch of where hourly jobs are clustered and where residents seeking those jobs live by prioritizing public transportation options to underserved communities. As part of Columbus, OH’s “smart city” grant from the USDOT, for example, the city launched an autonomous circulator bus that connects a low-income neighborhood to a high-opportunity job center to better facilitate employment access. Such transit options are particularly important during a pandemic, when essential services are vital and require the support of essential workers. When considering possible cuts to service, agencies should pay special attention to routes that serve essential services that may be necessary during future pandemics.

Other longer-term avenues to explore also include prioritizing system updates that incentivize cashless payments and reduce required touch points to limit transmission spread, and leveraging innovations in Mobility-as-a-Service systems to potentially use reservations on public transit as a way to control the flow of passengers.

In general, cities should leverage the disruptive nature of COVID-19 in order to rethink their transportation system and address existing gaps in service. Such actions could have major long-term benefits for both the health and mobility of a city.