Status Update, May 19: COVID-19 Crisis Impact on Transit & Shared Mobility

20 minutes Date Launched/Enacted: May 18, 2020 Date Published: May 18, 2020

Brief Summary

- This is the third status update on how cities and transportation sectors are impacted and responding to the COVID-19 pandemic. This update continues to assess trends in the mobility landscape by mode, with a specific focus on post-pandemic recovery.

- In the public transit world, there has been continued development of best practices for agencies and cities to protect employees and customers. Notable strategies are to stop collecting fares and allow for rear-boarding to limit contact with drivers, increase cleanings, and reduce service on non-essential routes.

- While bikesharing saw a large boom in ridership, many scooter companies have suspended operations and furloughed staff. With signs suggesting a sustained uptick in active transportation modes, some cities have rolled out plans to invest in infrastructure that supports micromobility.

- TNCs are seeing slow increases in ridership in areas that are beginning to reopen. However, TNCs are also facing pressure to reassess their protections for drivers, and in some cases, reclassify drivers as employees rather than contractors.

- Fixed-route transit has been temporarily reduced in many areas, but paratransit continues to provide an essential service to people who may be more susceptible to COVID-19, and advocacy organizations are working to support paratransit riders and recommend best practices for agencies

Introduction

This is the third installment of SUMC’s ongoing effort to explore how cities and transportation sectors are impacted by the novel COVID-19 coronavirus. The first status update, published April 8th, 2020, highlighted some of the ways public agencies and shared mobility operators responded to the initial weeks of the outbreak. The second update, published April 23rd, was organized by mode and explored the trends that emerged through the month of April, when most stay-at-home orders were in effect and cities established more comprehensive plans to address the crisis. This third update is also organized by mode, and continues to assess emerging trends in public transit, micromobility, ridesharing and carsharing, as well as other shared-use mobility services in early May as global attention begins to shift towards post-pandemic recovery.

SUMC will continue to track emerging patterns and responses as the COVID-19 crisis unfolds. Subsequent status updates on the coronavirus’s impact on transit and shared mobility will be published as new information is shared.

Public Transit

Since the on-set of the COVID-19 crisis, much attention has been paid to its impact on public transportation patterns around the globe. As previous status updates have explored, ridership on public transit dropped significantly in the weeks following the WHO’s declaration of a global pandemic on March 11th, leading to widespread budget concerns and temporary service cuts.

In more recent weeks, there has been continued development of the best practices that transit agencies and cities can apply to protect employees and customers, and organizations like NATCO and the National League of Cities (as well as companies like Transit) have continued to update their respective trackers detailing how agencies are responding to the various challenges posed by the crisis. Some of the most common responses have been to stop collecting fares and require rear-door boarding to limit contact with drivers, to increase the frequency of vehicle and facility cleanings, and to reduce service on non-essential routes. In fact, for the first time in its 115-year history, the New York City subway system was intentionally closed overnight to allow for more thorough cleaning of trains and equipment. Some agencies are also pursuing more innovative practices to address their customers’ mobility needs:

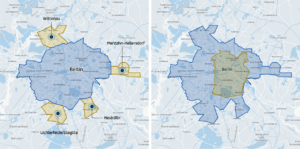

- In Germany, Berlin’s BerlKönig on-demand microtransit program (operated by Via Vans but a component of the city’s public transit system) adjusted the program’s service area to access 75% of hospital beds in the city, and it capped participating vehicles at 50% capacity. It also prioritized service to front-line workers by providing free transportation to healthcare personnel and changed hours of operation to better serve travel to medical shifts. Similar adjustments were also made to on-demand partnerships in Los Angeles, CA and Washington State;

Source: Via; map of expanded BerlKoenig service due to COVID-19

- New York City’s MTA launched a pilot program to install vinyl shields on buses to further separate passengers and drivers;

- In San Francisco, CA, the Bay Area Rapid Transit service is running longer trains and monitoring ridership levels to support social distancing;

- Although the Chinese city of Suzhou has begun to reopen, it continues to use its Transit Metropolis Project to “analyze[…] crowd distribution inside buses in near-real time and identif[y…] the volume of passengers in each vehicle through smart transit cards.” This technology could help customers better plan their travel to avoid the most crowded times during future disruptive events, and it could help cities adjust their service accordingly.

Towards the end of April and into early May, Asian and European cities began to lift their restrictions on movement, and businesses were permitted to reopen in phases. As non-essential workers return to their jobs in these cities, public transit ridership is expected to rebound, albeit slowly and likely not to pre-pandemic levels. Some specific examples of how transit agencies are responding to the challenges of re-opening include:

- Employees being provided with required protective materials like masks and goggles, and being trained on how to prevent virus transmission, as is the case in several Chinese cities;

- Municipal transit operators encouraging use of electronic payment methods, such as WeChat, Alipay or transit cards, as is being done in Beijing and Shenzen;

- Police and non-profit organizations distributing masks at metro stations and transit hubs as workers return to their commutes, as was seen in parts of Spain, where wearing a mask on public transit is now required; and

- Stricter regulations at transit platforms. In Rome, for example, only 30 passengers were permitted entry into stations every three minutes during a single 3-hour test period, train capacity was limited to 150 riders at a time, and indicators were placed on platforms to illustrate how far apart customers should stand. (For more in English, see here.)

Currently in the US, most markets remain closed, and about 40% of the American populace remains under varying degrees of stay-at-home restrictions. However, there is already speculation regarding what public transit will look like in the aftermath of the pandemic, despite the uncertainty surrounding when the crisis is likely to abate. Financially, worries abound about how transit agencies will be impacted long-term, with many experts anticipating that ridership will remain below pre-crisis levels through the coming months – if not years. Although over $26 billion was allocated to transit agencies in the first COVID-19 aid bill passed by Congress at the end of March, the heads of the New York MTA, New Jersey Transit, San Francisco BART, Pennsylvania’s SEPTA, and Atlanta’s MARTA have called on the federal government to include an additional $33 billion in funding for public transit in the next bill to alleviate some of the burden from the virus’s impact on ridership and increased cleaning costs. In addition to COVID-related budget shortfalls impacting existing service in the short-term, some planned expansions and infrastructure improvement projects may also be postponed. In San Antonio, TX, for example, the city’s mayor recent suggested that the ballot initiative planned for November that would launch an expansion of the VIA transit system may be delayed, because there may not be enough “bandwidth” for a successful campaign when voters are already consumed with worries about financial and health matters.

One optimistic long-term outcome of the COVID-19 crisis on public transportation may be a greater push towards establishing resiliency plans and localized action plans so that transit agencies and cities are better prepared to respond rapidly to changing mobility demands. Other longer-term predictions anticipate more public agency collaborations with private mobility operators, fewer people traveling during rush hours, and more passenger-flow monitoring.

Micromobility

As explored in previous SUMC COVID-19 status updates, micromobility modes like bikesharing and e-scootering have also been heavily impacted by the crisis. In major markets around the country, biking saw a boom in ridership just as the virus began to spread rapidly, as people were eager to avoid crowded public transit. However, when work-from-home orders and nation- or state-wide lockdowns were instituted, bike ridership dropped alongside public transit ridership and vehicle traffic.

Similarly, many scooter companies – facing declining use and uncertain lockdown timelines – chose to shutter operations and furlough staff. Some cities tried to encourage the operators to keep scooters on streets to help fill in mobility gaps resulting from reduced public transit service. San Francisco, for instance, categorized scooters as an essential city service and suspended some of its usual requirements on vehicle distribution; however, only Spin continued operating on San Francisco streets, while Lime, Scoot and Jump all paused local operations. For the markets where scooters continued to operate, most companies provided front-line workers with free or reduced access to better facilitate commuting to work.

One active transportation trend that emerged more clearly in recent weeks pertaining to the public sector was that more cities are pursuing pop-up bike lanes and pedestrian-friendly zones during the pandemic. For more on this topic in detail, see our recent case study: Pop-Up Mobility Paths & Open Streets due to COVID-19 crisis. Some examples of this trend include:

- Berlin, Germany using tape and mobile signs to temporarily widen bike lanes to accommodate more active transportation users;

- Bogota, Colombia opening 22km (13miles) of bike lanes overnight by repurposing car lanes, with plans to open 76km (47miles) in total throughout the crisis;

- Oakland, California launching its “Slow Streets” program to slow vehicle speeds and ensure roads can be more safely shared with bikers and pedestrians on 10% of city roads;

- Burlington, Vermont closing corridors to vehicle through traffic altogether, and designating others as “shared streets” on which drivers should drive slowly and be extra aware of cyclists and pedestrians; and

- Vilnius, Lithuania giving public space to bars and cafes to allow physical distancing during lockdown.

Oakland streets closed to Thru Traffic. Source: Oakland, CA

Although much remains uncertain about the long-term effects of the COVID crisis, as Europe slowly reopens, there are some signs that suggest that the pandemic could result in a sustained uptick in the use of active transportation modes like biking, e-scootering and walking. For example, modelling from London’s transit authority recently suggested the city could see a “tenfold increase in distances cycled, and up to five times the amount of walking compared with pre-coronavirus levels” following the crisis. In order to meet this increased demand for mobility paths and walkable routes, some Europe cities are releasing ambitious active transportation plans:

- Paris, France plans to invest heavily in expanding its existing bike lane systems after the city begins to open, with 650km of cycleways;

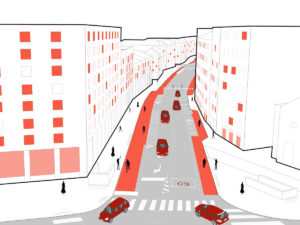

- Milan, Italy announced in April its Strade Aperte plan, which will result in a total of 35km (22 miles) of temporary bike lanes, widened pavements, and low speed limits to be deployed over the summer 2020; and

- Brussels, Belgium has given pedestrians and cyclists the priority throughout its entire city center, capping vehicle speed limits at 20 km/h.

Digital rendering of street part of Milan, Italy’s Strade Aperte plan; Source: City of Milan

In the US, advocates are also calling for similar plans that prioritize active transportation and micromobility options over cars in the wake of the pandemic:

- Streetsblog, Fixing New York’s Pre-Existing Transportation Condition

- Huffington Post, The Coronavirus Shows It’s Time To Remake The American City

- Streetsblog, Chicago must act now to prevent a post-COVID spike in driving and crashes

Already, some US cities have heeded these calls and are rolling out plans to invest in infrastructure that supports micromobility after the crisis. For example, Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan announced that about 20 miles of the city’s streets will be permanently closed to vehicle traffic to allow for safer walking and biking even after the stay-at-home order is lifted, and New York City is opening up two more miles of streets to pedestrians and cyclists in Manhattan, Brooklyn, Queens, and the Bronx.

Another way cities may prioritize mircomobility modes after the pandemic is by further exploring the role dockless scooters in particular can play in filling transportation gaps in city transit systems. With transit facing immense constraints in many cities, people are losing a critical backbone in transportation, and dockless scooters could be an undersung component to keep mobility networks moving and safely replace car trips. The University of Tennessee, Knoxville and Portland State University are collaborating on a new project to study how micromobility services like bikesharing and shared scooters can fill the transportation void in cities and help workers get to essential jobs during the COVID-19 outbreak. Such insights could lead to greater collaboration efforts between public agencies and scooter operators down the line.

TNCs & Carsharing

Transportation network companies (TNCs) are facing difficult times financially as a result of the COVID-19 crisis. Lyft is laying off nearly 1,000 employees and furloughing a further 288, and Uber cut 14% of its workforce. Via, too, has been forced to temporarily suspend operations of its on-demand ridesharing service in Chicago. Carsharing companies are also struggling: Maven, GM’s foray in the carsharing sector, was shut down permanently in April, including the component that made cars available to Uber and Lyft drivers.

However, there is some light at the end of the COVID-19 tunnel for these companies. In cities that are beginning to reopen, Lyft rides are slowly increasing, with the company claiming that rides were up 7% in the first week of May compared to the first week of April, with major markets like Chicago and Seattle seeing 35% and 25% increases respectively. Uber and Lyft have both asserted that going forward in the US, drivers and passengers will be required to wear masks and passengers will be encouraged to sit in the back seat and keep the windows open when possible, in an effort to prevent transmission of the virus.

Even after the crisis abates and travel picks up, some of these companies may continue to face fallout. In April, California filed a lawsuit against Uber and Lyft for classifying their drivers as contractors instead of employees, in violation of the state’s Assembly Bill 5, which was passed in September of 2019. The bill was established to push companies like TNCs that rely primarily on “gig workers” to classify those workers as employees, which grants them more protections like paid sick leave and minimum wage regulations. The lack of protections for gig-economy workers like Uber and Lyft drivers has been thrown into sharp relief by the pandemic, and this lawsuit has the potential to further raise awareness of these challenges. While public support for greater worker protections is still high, some states may choose to follow California’s lead and pass similar legislation.

Importantly, Uber and Lyft are not the only companies facing pressure to reassess their protections for employees. Online car retailer Carvana, for example, gained national attention after employees were sent a memo on April 27th that they either return to work or the company will “consider [them] to have abandoned or resigned from [their] position.” This ultimatum – return to work or lose your job – was issued while death rates from the virus in the US were still climbing.

One potential long-term outcome of the COVID-19 crisis for TNCs is potentially greater collaborations between mobility providers. Uber made headlines in early May when it announced that it was investing $170 in Lime and transferring its JUMP mobility brand (comprised of dockless scooters and e-bikes) to Lime. These efforts to integrate Uber and Lime’s shared bike and scooter operations – potentially spurred by the financial challenges of the pandemic – could signal a shift in the dog-eat-dog, war of attrition mentality that has marked the micromobility sector until now.

Autonomous Vehicles (AVs)

As mentioned in our previous COVID-19 status update, most AVs testing passenger routes were halted at the outset of the outbreak. Some experts are anticipating a renewed in interest in AVs following the crisis, particularly for driverless deliveries. In the nearer term, however, AV technology developer Waymo announced that it will resume testing its AVs in Arizona on May 11th after nearly two months of pause. Other AV pilot projects around the country are likely to follow suit and resume operations as restrictions and health concerns ease.

Paratransit

Although fixed-route transit has been temporarily reduced in many markets, paratransit continues to provide an essential service, particularly for customers with disabilities who may be more susceptible to the virus. To support these paratransit providers navigating the crisis, the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund published recommendations, which include installing a safety strap or other temporary barrier to prevent the use of front seats by passengers when possible, and developing procedures to ensure adequate gloves, wipes, hand sanitizer and masks are available for staff to assist safely when securing wheelchairs.

Rabbittransit employee sanitizes vehicle in mask and gloves during COVID outbreak; Source: rabbittransit

It is also important for paratransit providers to track expenditures made during the crisis, in order to secure reimbursement later. The National Aging and Transportation Disability Center has provided guidance on this matter for transit agencies, and it recommends reviewing the FTA’s Emerging Relief Program submission requirements.

For authorities seeking information on how the Summer Food Service Program and National School Lunch Program Seamless Summer Option can still provide meals to students in non-congregate settings and despite school closures, the USDA Food and Nutrition Service has issued guidance for COVID-19 waivers.

Some additional examples of transportation and mobility providers working to meet the specified needs of their paratransit-eligible customers not already explored in previous status updates are listed below.

- rabbittransit, a regional public transportation authority in Pennsylvania, partnered with the local health system to provide transportation to testing facilities and safe quarantine locations to families and the homeless;

- King County Metro’s Access Paratransit program expanded eligibility for its service to customers with disabilities who can no longer reach their essential destination through traditional service due to temporary service reductions. Customers need not already be certified for the program.

- Whatcom Transportation Authority in Washington state has partnered with a local food bank to deliver boxes of food to paratransit customers’ doors, thereby reducing the number of trips to the food bank and decreasing potential exposure to the virus.