Zero Fare Transit State of the Industry

30 minutes Author: Abby Mader, Francesca Lewis, Hani Shamat and Al Benedict Date Launched/Enacted: Dec 19, 2024 Date Published: December 16, 2024

Review of Zero Fare Programs in the United States

This Zero Fare Transit State of the Industry summary builds on the Zero Fare Case Study published by the Shared Use Mobility Center (SUMC) in 2022. The 2022 study offered a broad overview of zero fare programs throughout the United States (US), examining the motivations behind eliminating fares alongside the challenges and benefits faced by agencies that had pursued zero fare transportation. At the time, many transit agencies were interested in implementing full or partial zero fare programs. Some of these programs originated during the COVID-19 pandemic to decrease contact between riders and vehicle operators, increase ridership, and promote public transportation as an essential service, while others were aimed at alleviating transportation barriers.

This summary highlights the lessons learned from seven zero fare transit programs in a variety of operational contexts: urban, small urban, rural, tribal, and regional urban (see Table 1). Based on the Federal Transit Administration’s (FTA) Section 5307 Urbanized Area Formula Funding program definition, “urban” is defined as an urbanized area with greater than 200,000 population and “small urban” as an area with 50,000 – 200,000 population. According to FTA’s Section 5311 Formula Grants for Rural Areas program definition, “rural” areas are considered those with less than 50,000 population. FTA also considers eligible Tribal Transit applicants as “federally recognized American Indian or Alaska Native tribes as identified by the U.S. Department of the Interior (DOI) Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA).”

This study also explores how these programs have sustained funding, developed partnerships to support zero fare service, and interacted with nearby transit systems that charge fares. For some agencies that have reinstated fares after a zero fare period, this summary discusses the reasoning behind that reversion, along with payment technologies and new policy approaches adopted during the transition back to collecting fares. Table 1, Zero Fare Programs Reviewed in this Study, highlights the key attributes of each program.

Originally published December 2024, revised March 2025.

Table 1: Zero Fare Programs Reviewed in this Study

| Agency Size | Location | Agency Name | Urbanized Area (UZA) Population | NTD 2022 Unlinked Trips | Goals | Program Status |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Urban | Kansas City, MO | Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) | 1,689,556 | 10,572,362 | Safety, efficiency, and capacity | Permanent as of 2020, under evaluation in 2024 |

| Urban | Albuquerque, NM | ABQ Ride | 769,986 | 5,253,683 | Increase ridership and access to transportation | Permanent as of 2022 |

| Urban | Central Falls, RI | Rhode Island Public Transportation Authority (RIPTA) | 1,285,806 | 9,684,186 | Increase ridership and access to transportation in a defined area | Started in 2022, ended in 2023 |

| Urban | Olympia, WA | Intercity Transit (ITA) | 208,157 | 3,311,656 | Access to transportation, and reliability | Permanent as of 2020 |

| Rural | Blaine County, ID | Mountain Rides Transportation Authority (MRTA) | 24,866 | 488,383 | Increase ridership and improve access to transportation | Permanent as of 2020 |

| Tribal | Auburn, WA | Muckleshoot Tribal Transportation Program (MTP) | Tribal Area: 4,362 City of Auburn: 84,858 |

16,198 | Improve safety and access to transportation | Permanent as of 2017 |

| Regional (Urban) | Research Triangle, NC (Raleigh-Durham-Cary-Chapel Hill) | GoRaleigh, GoDurham, GoTriangle, GoCary, and Chapel Hill Transit | 2,106,463 | GR: 4,618,080 GD: 4,862,329 GT: 1,528,760 GC: 279,799 CHT: 6,139,158 Total: 17,428,126 |

With the exception of Chapel Hill Transit (longstanding zero fare program), the transit agencies moved to zero fare in response to COVID-19 and have since moved back to collecting fares or are planning to in 2025 | Ended: GR (2024), GT (2024), (2024) Potential through 2025: GD, GC Permanent: CHT (2002) |

In addition to the highlighted examples above, SUMC compiled a working list of Zero Fare Agencies showcasing past and current zero fare programs across the U.S. While not comprehensive, the list provides further insights into zero fare program examples across the nation.

This summary starts by defining zero fare transit and its varying implementation frameworks, discussing the key findings from the zero fare programs examined, and ends with the supporting zero fare program case studies.

What is Zero Fare Transit?

Figure 1: What is Zero Fare transit? Credit: SEPTA

Zero fare transit systems do not require passengers to pay a fare when boarding a public transit vehicle. As transit agencies work to create accessible transportation networks, many have recognized the barrier that a fare can pose for riders. Some people view transit fares as a regressive tax, disproportionately impacting lower-income riders who are already more reliant on public transit than their higher-income counterparts. Eliminating fares is one approach that transit agencies have taken to address this barrier, thereby minimizing the financial burden on riders while improving transportation access.

This paper refers to “zero fare” transit rather than “fare free” transit. While these terms seem interchangeable, the term “fare free” can overlook some of the complexities of how transit systems operate and are funded. While fares may be free to the rider, a transit agency still needs to recoup revenue that would have otherwise been collected through fares to support the system’s operations. Thus, agencies operating zero fare service often must tap into a dedicated funding source, like a sales tax levy, or reduce operational costs through other means. In this way, zero fare transit is not free but does remove the upfront financial burden on users.

This summary uses terms such as “fare collection” and “fare payment process” to describe different elements of how a transit agency gathers revenue from riders to use its services. In this work, “fare collection” refers to the technology of collecting fares, while “fare payment process” refers to the process itself of collecting fares.

COVID-19 Accelerated Zero Fare Programs

Figure 2: COVID-19 Accelerated Zero Fare Programs. Credit: Gold Coast Transit District

Although zero fare transit is not a new concept, the COVID-19 pandemic put a renewed focus on the practice. Before the pandemic, zero fare transit service was mostly seen in small urban areas, resort towns, and university communities. These settings are conducive to partnership building to help fund the service, particularly for targeted populations like university students or tourists. With COVID-19 came an emphasis on public transit as an essential service, and a widespread desire to make transportation accessible to those who rely on it. In many cases, large and small agencies across the country eliminated fares and used Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act funding to supplement farebox revenue losses. CARES funding also helped transit agencies maintain service levels (providing critical transportation access for those with no other means of travel), keep transit employees working, and support contactless boarding of vehicles. While this was a temporary measure for many transit agencies to continue providing transportation service through the pandemic, some agencies have decided to maintain zero fare service indefinitely, recognizing its potential benefits.

Types of Zero Fare Programs Limited Zero Fare Programs

Zero fare programs can take many forms, with some functioning as full system programs covering all routes and services, and others that are temporary or only apply to certain routes or areas. Transit authorities often use these temporary initiatives as pilot programs to evaluate the impacts of a long-term zero fare program.

Events and Seasonal Zero Fare

Cities and regions may offer a limited-time zero fare transportation option to support major events (concerts, festivals, conventions), or during seasons where tourism peaks (winter near a ski resort or summer in a beach town). This form of zero fare transit often involves meeting riders in a designated area (Park & Ride, shopping center, or transit stop) and transporting them to a key destination (festival grounds, event center, etc). Typically, these transportation options often operate on a short loop, making stops at other pickup locations a few times per hour. Zero fare transit during special events or peak seasons can often help to facilitate more efficient transit operations and ease travel for riders to key destinations and traffic-heavy areas.

Figure 3: Types of Zero Fare Programs: Events and Seasonal Zero Fare. Credit: Minnesota Valley Transit Authority

Some transit agencies chose to make transit zero fare for limited periods, typically corresponding with seasons and travel patterns. For instance, the Colorado Regional Transit District (RTD) (Denver, CO), in partnership with the Colorado Energy Office (CEO), implemented zero fare on all forms of transportation in August of 2022, better known as the Zero Fare for Better Air program. The RTD’s zero fare program strategically aligned with peak ozone levels in the region in hopes of improving air quality and promoting transit ridership through reducing the number of single occupancy vehicles on the road. This program proved to be successful, leading to an increase in ridership, and community interest in extending the program into July and August of 2023. Further, the Los Angeles County Metropolitan Transportation Authority (branded as “LA Metro”) ran an even more condensed program in 2024, limited to one day of zero fare, and offered free 30-minute rides with their bikeshare program. This program was created to bring attention to vehicle emissions in Southern California, while also familiarizing passengers with the metro system.

Zero Fare Zones and Lines

Another zero fare transportation option that various agencies offer comes in the form of zero fare zones and lines. These types of zero fare programs have proven to be effective in increasing ridership in traffic-heavy areas or near key destinations. Found typically in urban or suburban areas, they can target a specific transit line(s), or an area, or zone. Agencies have used these approaches to pilot zero fare programs and learn more about ridership patterns and operational costs. Boston Massachusetts Bay Transit Authority (MBTA) is using American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding to make several bus lines zero fare and the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) led a demonstration project under the FTA Accelerating Mobility Innovation (AIM) program to test geofencing as a means to support zero fare zones. The RIPTA demonstration project is discussed in more detail in this summary.

System-Wide Zero Fare Programs

Year-round, system-wide zero fare transit programs are a big step from temporary, or limited zero fare models, and require substantial planning, funding, and community support. Full zero fare programs eliminate fares across the entire system 365 days a year. Except for the RIPTA zero fare zone example, the summaries featured in this study focus on system-wide zero fare programs and are the focus of the following key findings.

Key Findings from Zero Fare Programs Examined in this Summary

Agencies have looked to zero fare programs to meet regional goals and improve access to transportation

Figure 4: Key Findings: Agencies Have looked to zero fare programs to meet regional goals and improve access to transportation. Credit: Pace Suburban Bus

Agencies have implemented zero fare programs to address a range of social and operational needs. A few of the agencies in this study leveraged COVID-19 relief funds to create programs that address key operational challenges like funding, staffing, and technology needs, whereas others addressed social challenges such as safety and access to transportation. Not all zero fare programs began due to COVID-19; some were established pre-pandemic and were offered primarily as a fair way to address social or operational needs. For instance, the Muckleshoot Tribal Transit Program (MTP) launched its zero fare program in 2017, out of concern for the safety and mobility of residents walking along a busy highway. Whereas, the Town of Chapel Hill established its zero fare program in 2002 in part to satisfy operational and economic needs by eliminating the fare payment process.

While the origins of zero fare programs differ based on the needs of the region and transportation situation, programs tend to place access to transportation at the center of the discussion. Our review of agencies found that both lower-density rural communities and higher-density urban areas have looked to zero fare as a solution to alleviate financial burdens on vulnerable populations.

Community perspectives are important to Zero Fare program sustainability

Gaining community support for zero fare transit can require agencies to navigate a range of perspectives. In some cases, communities have embraced zero fare programs, recognizing the value of increased access to transportation services or reduced congestion by trips shifting from cars to transit, this is true of Chapel Hill Transit (CHT) in North Carolina. Widespread community support for transit was more easily achieved due to a strong history of collaboration between key community institutions supporting the transit agency, such as the University of North Carolina and the Towns of Chapel Hill and Carraboro. Community members actively supported financial initiatives like a student referendum that allowed them to self-tax and eventually motivate the university and towns to increase their contributions to CHT.

Community engagement is critical to understanding transportation needs and building support for zero fare programs. In Olympia, WA, Intercity Transit Authority (ITA) conducted in-depth community engagement to better understand local interests in improving public transportation. The process informed service improvements across the transportation system. In Kansas City, MO, support for zero fare was built by uniting community members and local organizations who had previously supported fragmented zero fare initiatives for specific populations. The Kansas City Area Transit Authority (KCATA) has endured pushback from community members and RideKC (the brand representing its transit services) operators, citing increased criminal activity and cleanliness issues. Securing broad support for system-wide zero fare programs lays the foundation for program success and helps secure long-term funding, which minimizes their reliance on ephemeral operating revenues like COVID-19 relief funding.

The final round of COVID-19 relief funding was issued in 2023 with a deadline for expenditure set for late 2024. City centers are often at odds competing for limited funding and resources with their suburban counterparts, where the city center may support zero fare the suburban areas are often less supportive, whether it is because of lower levels of transit use in car-dominated suburbs, or negative perceptions regarding public transit. In the Kansas City region, for example, while there seems to also be a divide within the central city of Kansas City, MO, that’s also where most of the support for zero fare originates. The lack of a regional funding source has led to the local match component of the program being largely funded through sales tax measures in Kansas City, Missouri.

Zero fare programs are supported by a mix of funding sources

For many agencies, the pilot phase of their programs were funded through COVID-19 relief funding, which helped offset the loss of farebox revenue and support complementary paratransit services. Several of the agencies reviewed in this research used COVID-19 relief funding to catalyze their zero fare programs, which gave transit agencies the operating support needed for implementation. As of 2024, this relief funding is in its last year of distribution. With a fiscal cliff approaching, these transit agencies are looking to other funding opportunities or evaluating if and how they will reinstate fares.

Ensuring the financial sustainability of zero fare programs often requires funding from a range of sources including federal grants (formula, competitive, and relief), and local funding (taxes, local matches, and levies). Federal grants are awarded to transit agencies depending on program scale (service area, population, demographics). Albuquerque, New Mexico’s ABQ Ride benefits from a portion of the Gross Receipts Tax (7.65%) on all sales transactions, supporting roughly 76% of transit operating costs.

In addition, some programs are funded through competitive federal grants or special funding sources; for example, MTP receives a portion of its funding from the BIA, and through partnerships, similar to Chapel Hill’s partnership with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Whereas, pilot programs are typically funded through a one-time grant, which covers fare revenue for a short period.

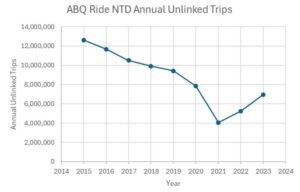

Zero Fare programs have boosted ridership, and supported improved operational efficiency

Zero fare programs often have similar goals, objectives, and performance measures. The most common performance measure is ridership. Ridership typically increases for all zero fare services offered, such as fixed-route, on-demand/microtransit, and paratransit services. The per-passenger operating costs for these services differ, based on the ridership of a fixed-route and more personalized on-demand services including paratransit. Removing fares might also contribute to simplifying operations, by reducing boarding times, eliminating fare related disputes and in some cases, lowering overall operational expenses. These measures contribute to operational efficiency and improve productivity metrics, such as boardings per revenue hour, a measure that can help transit agencies qualify for additional funding. Other relevant operational metrics include on-time performance, bus capacity, and bus operator satisfaction. ABQ Ride’s zero fare program has helped boost ridership numbers to near pre-pandemic levels. Notably, ABQ’s 2022 ridership survey notes that 88.3% of its passengers have a household income below $35,000/year, and over half of its riders do not own a car. With many new entry-level jobs located in suburban areas, public transportation access is essential for connecting individuals to work. Additionally, zero fare programs might play a role in shaping and improving public health. Researchers are studying whether zero fare transit helps to increase physical activity, leading to lower obesity rates and fewer diagnoses of diabetes and heart disease. Researchers are also studying how zero fare transit improves access to health care, employment, and sources of healthy foods.

This research found that upgrading to a new fare collection system is often financially unfeasible for transit agencies, and repairing the older systems can be costly, which tends to be the case for small urban, rural, and tribal agencies. For example, in 2019, prior to the zero fare program in Olympia, WA, ITA’s fare revenue accounted for 10% of its operating costs. Rather than replacing its outdated system, eliminating fares addressed the financial challenges of procuring new fare technology and supported its access to transportation goals. This research also found that zero fare programs can support transportation goals by increasing ridership and reducing the number of single-occupancy vehicles on the road.

Perceptions of funding, safety, and cleanliness are reported challenges

Zero fare programs offer benefits to both agencies and passengers, but can also come with a set of operational, financial, and administrative challenges. While agencies of varying sizes face different challenges, safety and long-term funding tend to be consistent issues across all zero fare programs. One of the most polarizing factors about zero fare programs is safety. Crime on board public transportation has increased over the past decade. While this took place in agencies across the country and with no clear association with fare costs, agencies with zero fare programs have reported issues with passengers refusing to disembark transit—riding routes from end to end (loop riders), disruptive behavior, or bringing unwanted items aboard.

However, in some cases, like ABQ Ride, crime categorization doesn’t paint the whole picture of what is happening onboard public transit. For ABQ Ride, public transit-related crime increased by 40% during the first year of its zero fare program leading to mixed public opinions. Some residents noted that public transit vehicles have become less clean and unsafe due to increases in crime, while others noted that cleanliness on board has remained largely the same. Despite these mixed opinions, the ABQ transit board voted to make zero fares permanent in 2023. ABQ Ride also reported much of the crime was vandalism or drug use near transit stops, with violent crime on buses having decreased.

To mitigate perceptions of safety on transit some agencies with zero fare programs have hired private security or have an increased police presence onboard. However, this staff change can both strain budgets and create new community concerns about the over-policing of vulnerable populations. For instance, ABQ Ride has hired additional security enforcement staff to handle transit-specific violations on the bus or near stops. Their additional security staff, known formally as Safety Officers, differ from standard Albuquerque police, helping reinforce safety on public transit while assisting with cleanliness expectations. While additional staff does help with crime and cleanliness, ABQ Ride must now fund 18 new security-related positions. Similarly, prior to implementing zero fares in Chapel Hill, most disputes on CHT vehicles were fare-related. These disputes were minimized when zero fare services were launched eliminating much of the conflict between riders and operators. However, CHT has also seen an increase in concerns about safety and cleanliness since COVID-19. The agency has mitigated these concerns through more frequent vehicle changes, the development of a crisis intervention unit, partnerships with the local police department, and a commitment that access to transit service is important for all community residents.

Some agencies shifting back to fare collection are taking the opportunity to upgrade fare collection technologies and policies through lessons learned during zero fare pilots

Figure 5: Key Findings: GoRaleigh contactless payment. Credit: GoRaleigh

If the fare payment process is reinstated, it may not equally impact all transit riders. Agencies can create programs that allow certain passengers to ride for free, for a reduced cost, or implement fare capping, which sets a limit for how much passengers can spend on transportation on any given day, week or month—based on the cost of a fare pass. Typically reduced-cost programs will support a wide range of passengers, including students, older adults, veterans, low-income households, and other vulnerable populations. While some of the programs evaluated in this research have made zero fare permanent, others have eliminated it, or are evaluating the future of zero fare. Examples include the Research Triangle transit agencies, with the exception of Chapel Hill Transit, which will remain zero fare per its previous policy, GoRaleigh and GoTriangle have reinstated the fare payment process, and GoCary and GoDurham are planning to reinstate fares in June 2025. The RIPTA zero fare demonstration project ended with no plans to reinstate it, and KCATA is evaluating the future of its zero fare program due to budget and other constraints.

When an agency chooses to end a zero fare program—a process that requires community outreach, and an analysis of fares, and a vote by the transit board—fares can be reinstated. While it is up to an agency to determine the best method of fare reinstatement, many will try to upgrade the fare collection technology and address accessibility needs.

For example, when GoRaleigh reinstated fares, it moved to a closed-loop contactless payment system, which allowed for the implementation of fare capping and other reduced fare programs for qualified riders. While discounts for various rider populations have long been applied without contactless payments, fare capping largely depends on it, and the new payment technology helps to more easily manage and oversee all kinds of discount programs and other fare policies.

Other lessons and opportunities have emerged from zero fare programs even if they were not made permanent. While the RIPTA demonstration project has no plans to reinstate its zero fare program, the pilot offers valuable lessons on using technology to geographically target zero fare policies to serve particular neighborhoods and support access. KCATA is also exploring its fare payment collection options as it evaluates whether to reinstate fares. KCATA is considering both closed-loop and open-loop payment technology as it evaluates the future of its zero fare program.

Conclusion: The future of Zero Fare programs is mixed

Zero fare programs have evolved over the years, shifting from small-scale, niche programs focusing on improving operational efficiencies to today’s strategic community-centered initiatives focused on supporting vulnerable populations. Several agencies started their system-wide zero fare programs by offering zero fares on a single route or targeting specific groups, such as low-income riders, veterans, or individuals with disabilities. KCATA leveraged this approach to pilot the program, collect user feedback, and analyze data—and is now in the process of evaluating the future of zero fares. In response to COVID-19, there was a shift in focus as zero fares were a way to limit interactions between riders and vehicle operators, while reducing the financial burden for lower-income individuals most in need of public transportation service.

More transit agencies are also evaluating the potential benefits and challenges of hosting a zero fare program by exploring the impact of zero fare transit on long-term transportation goals.

The programs discussed in this summary help demonstrate the uncertain future of zero fare programs since the onset of COVID-19. As COVID-19 relief funds near an end, transit agencies are confronted with finding new funding sources to sustain zero fare programs or eliminate them. While there are many benefits of zero fare, as it supports transit ridership and can improve operational efficiency, its associated challenges can complicate this decision. In addition to funding, public perception and safety (both perceived and real) tend to be at the center of this discussion and will undoubtedly play a factor in the future of zero fare programs. At the same time, advocates are working hard to make the case for zero fares. Zero fare programs like CHT demonstrate the importance of strong community partnerships fostered by a transit culture. For example, in Chapel Hill, widespread community support for enhancing transit options outweighed plans to widen streets and add parking facilities. This summary also finds that the financial constraints of zero fares are felt more by larger transit systems that have more transit users and higher operational costs than smaller and rural-based transit agencies.

When transit agencies revert to collecting fares, they often take the opportunity to upgrade fare technology and collection policies. While new payment technology can include substantial capital costs, there are benefits in that these investments can also improve accessibility to riders through both targeted programs and broader approaches, such as fare capping. While the future of zero fare is uncertain, its benefits are well established and will likely help to shape future fare payment policies.

Zero Fare Program Summaries

Zero fare programs take many forms and iterations. The following program summaries highlight examples in urban, small urban, rural, tribal, and regional contexts. The zero fare programs differ based on their objectives, goals, and geography.

Large Urban Transit Examples

Kansas City, MO – Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) – RideKC

Figure 6: Large Urban Transit Examples: Kansas City, MO, Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) – RideKC. Credit: Way to go KC

In 2019, the Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) launched its zero fare program, targeting vulnerable populations such as students, veterans, recovering addicts and people experiencing homelessness through the Opportunity Pass program. At the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, the RideKC zero fare program expanded to include all riders, funded by federal relief through the CARES Act. This initiative made Kansas City the first major US city to fully adopt zero fare transit citywide. Notably, the city’s streetcar, RideKC, has operated as a zero fare service since its opening in 2016, potentially laying the groundwork for following zero fare programs. However, KCATA has recently been considering reinstating fares in anticipation of a potential $30 million financial cliff expected in 2025.

Kansas City Begins Zero Fare Program Implementation

KCATA operates additional services such as the MAX bus rapid transit service, RideKC Freedom paratransit service for seniors and individuals with disabilities, and RideKC Van vanpool services. The decision to implement a zero fare program was part of a broader strategy, recognizing that farebox recovery accounted for 10% of KCATA’s operating budget. KCATA projected an annual savings of $1 million in fare-related expenses by eliminating the fare payment process on RideKC buses helping to offset the cost of implementing zero fares. The city also contributed $4.8 million in additional revenue, and KCATA evaluated its management costs.

KCATA started its zero fare services by first offering zero fare to specific groups or populations, gradually building the program, and forming partnerships with local community institutions. This gradual implementation allowed the agency to more easily embrace a fully zero fare service and gain community support since many riders were already benefiting from the group specific zero fare programs. KCATA launched the full zero fare program with support from the City Council and the mayor but also from a variety of community members who supported the program for its potential to increase access to vital opportunities such as job fairs and interviews and essential services such as healthcare, grocery stores, and educational facilities.

The RideKC zero fare program provides fixed-route bus and paratransit service, within KCATA’s bi-state jurisdiction, encompassing Cass, Clay, Jackson, and Platte counties in Missouri, as well as Johnson, Leavenworth, and Wyandotte counties in Kansas. The program is primarily funded by CARES Act funds, which is projected to be depleted by April 2025. Additionally, it receives financial support from the Kansas City, MO, ½ cent public mass transportation sales tax established in the early 1970s and a 3/8ths cent sales tax for buses enacted in 2004, renewed in both 2015 and 2024. KCATA operates additional services such as the MAX bus rapid transit service, RideKC Freedom paratransit service for seniors and individuals with disabilities, and RideKC Van vanpool services. Before the zero fare program, a single ride on RideKC buses cost $1.50, and a monthly pass was $50.

Ridership has varied over the years of KCATA’s zero fare implementation. As experienced by other transit agencies around the nation, KCATA recorded lower ridership during 2020 and the following years. By 2023, ridership had returned and even slightly surpassed pre-pandemic levels, with just under 12.2 million rides compared to about 12 million in 2019. In 2023, the system supported more than one million rides monthly and 35,000 rides daily.

Safety

The security situation on RideKC buses involves several complex challenges. Before the zero fare program, most conflicts revolved around fare disputes; however, and since implementing zero fares, confrontations between riders have become more prevalent. The absence of barriers for the fare payment process allows for open access to the buses leading to new issues between operators and riders who fall asleep or who refuse to deboard at the end of a route. After the first year of zero fare programming, the total number of incidents where supervisors were called decreased 39%, but there has been an increase in incidents on board these buses in recent years.

Since 2016, KCATA has partnered with the Kansas City Police Department to employ two full-time police officers to respond to incidents involving passengers or drivers. These officers are in uniform and stationed in patrol cars, positioned to quickly respond to incidents as they arise. KCATA installed plexiglass barriers to enhance safety by separating drivers from passengers in 2016 to add an additional barrier. Currently, KCATA employs four police officers and has a team of 30 armed security guards patrolling the bus system.

The absence of barriers for the fare payment process also allows for open access to the buses leading to new issues between operators and riders who fall asleep or who refuse to deboard at the end of a route. The increased number of loop riders has added challenges for drivers and security, leading to potential safety risks. A 2024 survey found that 92% of operators who have worked at KCATA since before 2020 disagreed or strongly disagreed with the statement ‘The safety of bus riders/operators has improved’.

Safety issues related to rider behavior and cleanliness on vehicles and at bus stops are increasingly becoming a challenge for RideKC. In response, KCATA has implemented new policies aimed at improving hygiene and cleanliness such as banning certain items from being brought on board and establishing a process to ban individuals from the system but enforcement of these policies is often difficult to carry out. Safety and security concerns are not directly linked to zero fare policies, it remains a concern that impacts the safety and experience of riders.

Funding

KCATA is encountering challenges as funding sources become limited. In fiscal year 2025 the agency may face a significant funding gap as COVID-19 relief funding diminishes. Another piece of this financial strain is the growth of paratransit services contributing to higher operating expenses. Since implementing the zero fare program, RideKC’s paratransit services have greatly increased adding approximately 36,000 trips and resulting in around $2.2 million increase in expenses. Additionally, rising costs associated with enhanced security measures are adding about $1.6 million to KCATA’s financial burden. The financial challenges are also compounded by the agency’s loss of fare revenue.

One strategy KCATA is trying to utilize to generate revenue for its operations is through service contracts with municipalities in its service area. The agency has begun increasing costs to contract its services as a method to increase revenue and maintain operations. However, recently, several municipalities have opted to not renew their contracts for RideKC services.

The City of Blue Springs, MO, decided not to renew their contract, citing increased costs to be the motivation. Blue Springs shared its plans to use the previously allocated funds to contract with another public transit provider that offers services for seniors and individuals with disabilities, that is already well utilized within the community. Along with Blue Springs are the communities of Gladstone, MO, and Grandview, MO, which stopped service in September 2024 and May 2024 respectively, and Raytown, MO, which opted for on-demand transit in June 2024. Johnson County, KS, still contracts to receive services with RideKC but withdrew from its agreement with KCATA to now manage day-to-day transit operations within its own public works department. Despite these contract non-renewals, KCATA continues to explore opportunities to partner with municipalities that are not yet contracting to provide services to their residents.

Other strategies, such as a sponsored zero fare program or fare reinstatement, may be implemented if service contracts are not able to support the agency. Sponsored zero fare programs involve financial contributions from one or multiple private businesses or organizations to help sustain zero fare transit service for riders. KCATA’s zero fare program highlights the possibilities of private sponsorship, with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas City committing up to $1 million to support the program. However, this funding was paused following the announcement of the CARES Act and has yet to be realized.

Research

Several studies, both ongoing and completed, are examining the implications of zero fare on RideKC buses. These studies reflect a growing interest among various organizations and institutions in understanding the potential benefits of zero fare programs and their impacts on specific populations.

A 2021 study for the Urban League of Greater Kansas City found that over 80% of RideKC users reported that the zero fare program improved their ability to access food, healthcare, and employment. The survey data suggest that this initiative has significantly advanced access to transportation, with nearly 90% of riders stating they use the services more frequently due to the zero fare policy. In 2022, the Mid-America Regional Council (MARC) released a zero fare impact analysis reviewing the community impacts of zero fare. Using MARC’s economic forecast tool, the study found that continuing zero fare may have a positive economic impact, potentially raising regional employment by 24 to 83 jobs, increasing economic output by $4.2 to $13.8 million and increasing personal income in the community by $1.3 to $4.6 million. Currently, the University of Missouri-Kansas City and Children’s Mercy Hospital partnered to study the health benefits and implications of zero fare buses. This federally funded research, supported by grants from the National Institutes of Health and the U.S Environmental Protection Agency (US EPA), aims to determine whether free bus rides help people get more physical activity, leading to lower obesity rates and fewer diagnoses of diabetes and heart disease. Preliminary findings suggest that removing the barrier of fares may enhance health, improve access to healthy food, and provide better access to healthcare and employment, further bolstering the positive impacts of zero fare programming.

Findings from the various studies on RideKC’s zero fare suggest a range of benefits, particularly surrounding the potential to enhance public health, improve economic opportunity and foster greater mobility among underserved communities. These insights will be critical in shaping future transit policies and initiatives.

Kansas City Considers Moving Away from Zero Fare

In early 2023, KCATA announced plans to consider reinstating fares for RideKC fixed route services primarily out of a need to increase revenue to continue operating services at the same level they are now. The agency is exploring several revenue-generating opportunities such as contracting services with more suburbs or partnering with business, education institutions and nonprofits, and nonprofits that benefit from the transit system.

In July 2023, the KCATA Board of Commissions authorized consultants to conduct a study to research how reinstating fares could help KCATA generate revenue and address ongoing safety concerns for riders and bus operators. Findings of the study were shared at KCATA’s December board meeting and claimed introducing fares could generate up to $7.1 million in unrestricted funds annually but warned it could result in a drop in ridership by as much as one-third. Also noted was the potential to save on ADA paratransit from shifting trips to fixed route or on-demand services and address ongoing safety and security issues for riders and drivers. The study recommended KCATA develop a detailed fare implementation plan in combination with public outreach efforts.

Reinstating fares could provide unrestricted funds for capital and service improvements, save on ADA paratransit from shifting trips to fixed route or on-demand services, allow for reduced fares for vulnerable users, and help address ongoing safety and security issues for passengers and drivers

An estimated $2.5 million to $6 million is needed to replace outdated fare payment systems on RideKC buses to collect fares again. If KCATA reinstates fares, the agency is interested in an open-loop contactless mobile payment system that would streamline transactions and boarding. One solution in consideration are ticket vending machines located off of the vehicles which would help users board more efficiently. The agency is exploring low-income based fare programming to ensure access for riders if fares are reinstated. A card-based system could enable fare capping and policies to limit cash payments, such as electronic transfers only. Fare capping has significant accessibility implications, allowing the most frequent riders, often with limited cash available, to benefit from bulk discounts on daily, weekly, or monthly passes without the high upfront costs. This technology automatically calculates the maximum fare based on usage, effectively capping costs over a set period. While fare capping can be implemented in both open-loop and closed-loop payment systems, open-loop technologies lower barriers, making it more accessible for a broader range of riders. However, if fares are reinstated, farebox recovery is estimated to account for less than the 10% of operating expenses achieved in 2019, which would not fully address KCATA’s anticipated fiscal cliff. (Personal Communications, KCATA) The decreased projected fare recovery could be attributed to the fare capping or reduced fare programs the agency plans to implement upon fare reinstatement.

Support from community members was divided between those against bus fares and those in favor of bus fares. At the January 2024 board meeting, ten community members of a local organization, Sunrise Movement KC, voiced their opposition to fare reinstatement. Additionally, over 100 emails from group members opposing the fare implementation plan were recorded, with many expressing how zero fare buses have positively impacted their daily lives. At later board meetings, community members, associated with other local groups such as Greater KC Policy Coalition, also spoke in favor of continuing the zero fare program. Various other community members, including KCATA operators, shared their perspectives on the issue, both supporting and opposing the program. Community members who advocate for the zero fare program cite its positive impact on the community by expanding access to healthcare and job opportunities.

As of January 2024, KCATA’s Board of Commissioners made the unanimous decision to pause the start of the zero fare implementation plan to continue studying the impact of having fares or not on RideKC buses. The agency continues to work with consultants to study various aspects of the fare system. These initiatives have involved strengthening outreach efforts to riders and scenario planning for possible budgets. In June the agency noted it still does not have a clear definition of functional zero fare or ‘functional fare free’, a requirement to be studied as directed by the most recent contract between Kansas City and KCATA. This must be defined before the agency can move forward with beginning a fare implementation plan. If conducted, the fare implementation plan will evaluate factors such as reduced prices for eligible riders, new ticketing systems, and opportunities for partnerships.

Albuquerque, NM – ABQ Ride

Figure 7: Large Urban Transit Examples: Albuquerque, NM – ABQ Ride. Credit: FTA NTD transit data.

In 2022, Albuquerque, New Mexico’s three transit services – Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) service, Albuquerque Rapid Transit (ART), paratransit service, Sun Van, and standard fixed route service ABQ Ride – launched a zero fare transportation pilot. While ART and Sun Van are housed under ABQ Ride, piloting for their service only ran for one year and four months, while the remainder of ABQ Ride’s services ran for two years before becoming a permanent zero fare program. Adopting a permanent zero fare program across the three transit systems made Albuquerque one of the largest cities in the US with zero fare transit alongside Kansas City. While all three transit systems play an important role in serving transportation options across the region, ABQ Ride is the largest in terms of ridership and operational costs.

ABQ Ride decided to move to zero fare after experiencing nearly a decade of declining ridership exemplified by the pandemic. The initial pilot phase had several key objectives, including increasing ridership and promoting access to social and economic opportunities. This initiative aimed to ensure that residents who depend on public transit for essential services – like commuting to work or accessing healthcare – would have access to an affordable means of transportation. According to the city of Albuquerque, ABQ RIDE serves an average of 23,800 riders daily, 88 percent of whom live in households with an annual income of less than $35,000, highlighting the critical role that public transportation plays in supporting lower-income residents. This transition to a permanent program was supported by an increase in ridership (roughly 56% of 2019 pre-pandemic ridership in 2022, and nearly 75% in 2023), and access to funding to sustain the program.

As one of New Mexico’s largest cities, Albuquerque benefits from its size and urbanized population, increasing federal funding and formula grant eligibility. In terms of capital expenses, ABQ Ride’s Zero Fare program is primarily supported through a combination of federal funding such as the Urbanized Area Formula Grant (5307) and the Capital Investment Grants (5309). 5307 funding provides financial support for daily operations in transportation systems. In 2022, Albuquerque utilized nearly $18 million of federal funding to improve operational support and bus infrastructure. The main improvements ABQ Ride is aiming to address are its old bus fleet and staff vacancies.

In terms of operational expenses, ABQ Ride largely relies on local funding. This revenue is mainly generated through Gross Receipts Tax (GRT), a 7.65% sales tax that is collected through sales transactions in Albuquerque, with 20% of the total GRT collected allocated to improving public infrastructure. This tax applies to a wide range of transactions, including retail sales and services. The collected funds are distributed among local public services, including ABQ Ride. In 2022, 76.7%, or $44 million of ABQ Ride’s total operating expenses came from local government revenue.

Figure 8: Large Urban Transit Examples: Albuquerque, NM – ABQ Ride. Credit: UrbanAQ

At the beginning of the zero fare pilot, community members were apprehensive about the sustainability and longevity of the program. Some worried that without fare revenue, there would be service cuts leading to overcrowding and longer wait times. Despite these concerns during the piloting phase, the city made the decision to make the zero fare program permanent. While Albuquerque resident’s perception of the program has largely changed over the past couple of years, negative opinions of the program remain. Some residents believe that eliminating fares has made buses more available to individuals who don’t necessarily rely on them for transportation and may use them as places to loiter with disruptive or criminal behavior. Despite this speculation, the City of Albuquerque and ABQ Ride have taken measures to improve safety and security on their vehicles including increased security presence, video surveillance on board, and the addition of an app for users to report safety violations.

One of the largest issues that ABQ Ride has run into is service availability stemming from a driver shortage. In September of 2024, ABQ Ride reported that it had 106 positions to fill, leaving the agency with a 40% vacancy rate. The shortage of drivers has caused ABQ Ride to scale back its operations and reduce the number of routes, and route frequency on existing transit lines. ABQ Ride acknowledges that service quality is crucial to maintaining a strong passenger base, and is currently allocating funding to fill driver vacancies and improve service. Ultimately, ABQ Ride wants to reach a customer base that relies on public transportation for more than just essential services through service expansion and improvements by running off-peak hours. In addition, ABQ Ride plans on doing extensive community outreach to ensure that the needs of passengers are being met.

Central Falls, RI – Rhode Island Public Transportation Authority (RIPTA)

Figure 9: Large Urban Transit Examples: Central Falls, Rhode Island Public Transportation Authority (RIPTA). Credit: RIPTA

In March 2022, the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) launched Ride Free Central Falls, a pilot program in a small, densely populated city that examined how fare policy and geofencing technology could influence transit ridership. Geofencing technology is a service that utilizes Global Positioning System (GPS) signals to set up virtual boundaries around an area of interest. For this project, RIPTA created a geofenced zone around the City of Central Falls. Once a mobile device entered the geofenced area, the technology automatically sent out a notification to alert users.

The City of Central Falls is Rhode Island’s densest city; it spans only one square mile but is home to about 20,000 people, many of whom are Hispanic, low-income, and rely on public transit for commuting. This setting provides RIPTA with a large participant pool in a small enough area to be a suitable test ground for the pilot. RIPTA uses an account-based fare collection system to manage fares. Riders can board vehicles by using a preloaded smart card or mobile app at a validator, or by paying cash. During the pilot, RIPTA created a geofenced zone that bordered the entirety of Central Falls. When a passenger used a Wave card or mobile app at a validator anywhere within Central Falls, the geofencing software would communicate with the Wave system to automatically waive the fare. Thus, the pilot enabled free one-way rides for Central Falls residents.

Ride Free Central Falls was funded primarily through a $244,000 AIM grant from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA), with an additional $50,000 from the City of Central Falls. This funding included considerations for anticipated lost fare revenue. In 2019, RIPTA’s fare revenue accounted for 19% of its total budget. (Personal Communications, RIPTA)

One of the primary goals of this project was to explore how new technologies can enhance mobility innovation and encourage riders to engage with the program. The geofencing technology facilitated contactless payment and ticketing while providing RIPTA access to valuable ridership data which can be utilized to inform future transit policy on a city, state, and national level. Additionally, this type of technology paves the way for targeted marketing partnerships that could boost ridership, allowing entities such as universities, businesses, or social service agencies to sponsor rides in specific, limited areas.

The pilot program announced an extension and expansion of the service area to Pawtucket-Central Falls Transit Center leveraging the remaining funds from the AIM grant. Launched in March 2023 and concluding in December 2023, the expansion aimed to promote the use of the new transit center and encourage residents of the Pawtucket and Central Fall areas to consider multi-modal trips to Boston, MA.

The performance measure used to track this program and its outcomes was the monitoring of WAVE card taps to gauge program reach. As of September of 2024, the agency’s ridership stands at approximately 70-75% of pre-pandemic levels. RIPTA also utilized surveys, focus groups and travel trends analysis to monitor the effectiveness of the program and understand community perceptions.

The program encountered challenges at various stages of the program. In terms of outreach, RIPTA had difficulty connecting with riders and encouraging them to transition from cash payments. Additionally, RIPTA discovered that riders were not as motivated to use the bus with zero fare as anticipated, citing infrequent and slow service as more inconvenient than paying a $2 fare. The agency also found that the geofenced zone was limiting, noting that riders only benefited in one direction. For trips starting outside the geofenced zone but ending in the geofenced zone, zero fare service does not apply.

A geofenced zone is an innovative approach to consider when implementing a zero fare zonal program. This model provides advantages such as contactless payment and efficient boarding. However, it also presents challenges for trips outside of fare zones, transfers, and multi-jurisdictional travel. To best utilize geofenced technology to implement zero fare the unique context of the community and region must be considered in the planning process.

As a result of this program, RIPTA gained valuable insights into the advantages and disadvantages of zero fare programs. This experience has prompted the agency to further explore zero fare within a broader discussion on enhancing the quality of life through improved access to transit systems. It raises important questions about whether zero fare alone can meet the actual needs and desires of the community, particularly concerning larger goals like improving air quality and vehicle miles traveled.

Currently, RIPTA has no plans to reimplement or pursue a zero fare system as it anticipates a $31 million deficit at the end of the 2024-25 fiscal year. Instead, the agency aims to provide more frequent, convenient, and reliable service to encourage more people to choose public transit over driving, as outlined in the Transit Forward RI 2040 Master Plan. Moving forward, RIPTA may put further attention toward promoting the advantages of the WAVE account-based fare collection system statewide, particularly focusing on fare capping.

Small Urban Transit Example

Olympia, WA – Intercity Transit Authority (ITA)

Figure 10: Small Urban Transit Example: Olympia, WA – Intercity Transit Authority (ITA). Credit: NW News Network

In Olympia, Washington, Intercity Transit (ITA) launched a five-year zero fare program in 2020 to eliminate the need to replace outdated fare collection equipment, increase access to services, and reduce travel times on fixed routes and dial-a-lift services. This program was quickly extended in 2021 until January 2028 or until the return of pre-pandemic fixed route service, whichever comes first.

ITA operates 18 fixed-route services serving Olympia, Lacey, Tumwater, and Yelm covering an area of about 101 square miles. The agency also provides door-to-door service for people with disabilities and specialized vanpool programs. Commuter vanpool services were zero fare from March 2020 to June 2021. It is now available at a flat rate fare based on the total round trip miles. Before the zero fare program was implemented, a ride cost $1.25, a daily pass was $2.50, and reduced fares were provided for riders based on age, disability of Medicaid card holder eligibility. In 2019, fare revenue accounted for just under 10% of ITA’s operating costs. Starting from a point of lower ridership and lower fare revenue across the system, it was financially viable to implement zero fares for all users.

The opportunity to move to a zero fare program primarily stemmed from the need to replace the outdated farebox systems inside the buses. The agency explored and evaluated various options to update its outdated system such as magnetic swipe cards, contactless RFID cards, and mobile passes. Many existing riders requested that the agency integrate fares with the One Regional Card for All (ORCA) system utilized by surrounding transit systems in Pierce, King, Snohomish, and Kitsap Counties. However, the cost to install and operate ORCA exceeded the expected fare revenue, and the ORCA program was set to be replaced, which would delay installation of the new system for an additional two to four years. The zero fare program aims to simplify travel by eliminating the need for riders to utilize multiple fare collection systems therefore enhancing user experience, reducing operational delays, and alleviating stress on both riders and operators.

Operations of ITA, including the zero fare initiative, are funded by a 0.4% sales tax established under Proposition 1, in 2018, to expand transit services within the agency’s service area which includes Lacey, Olympia, Tumwater, and Yelm. This tax was estimated to cost the average household an increase of $2 – $5 per month, depending on spending habits. Preceding the sales tax, ITA was largely funded by an 80% federal match to purchase buses and fund capital construction that was eliminated from the federal budget for four years, with only a small portion returning in 2016. In 2019, ITA’s fare revenue accounted for less than 2% of operating revenue or $225,000, which was largely offset by the support of local businesses. The agency determined, given the capital and operational costs of a new farebox system, that investing in faster service, increased ridership, and improved access to transportation offered greater benefits to the community.

ITA garnered significant community support by utilizing the zero fare program as a means to implement the goals outlined in Proposition 1. Community engagement revealed a strong desire to improve access, particularly for those who are low-income, elderly, or people with disabilities. Public forums highlighted that access and accessibility was the primary concern of residents, prompting officials to find solutions to address these needs. The zero fare program was promoted by emphasizing similarities to other free community services, such as libraries and parks and by highlighting the potential benefits of reduced congestion for local residents. Since October 2018, the agency has also had a Community Advisory Committee (CAC) consisting of 20 volunteer members who provide input to the agency on various issues such as service changes, strategic plans, budget, and fare structures.

ITA has encountered challenges along the way, particularly with recruitment and staffing. While aggressive efforts to recruit and train operators led to some service restoration, staffing shortages, and reduced service levels continue to be an issue. Like many agencies, ITA has faced negative perceptions of the zero fare program, with community members expressing concerns before its launch. To address these concerns, ITA has focused on developing and enforcing a strong rider code of conduct and training operators and operations supervisors to handle potential challenges.

Overall ridership increased by 20% in 2023 compared to 2022 annual boardings and stands at approximately 85% of pre-pandemic levels. These figures suggest a favorable response to the zero fare initiative, which may have contributed to the gradual increase in ridership. In April 2023, the program received $1.8 million in Community Project Funding aimed at improving bus stop access for the zero fare initiative, which will renovate 145 frequently used stops to enhance operational efficiency and reduce travel times. The zero fare program is set to continue until either 2028 or three years after service levels return to pre-pandemic conditions when the city will evaluate the program’s effectiveness to decide if the program should become permanent.

Rural Transit Example

Blaine County, ID – Mountain Rides Transportation Authority (MRTA)

Figure 11: Rural Transit Example: Blaine County, ID – Mountain Rides Transportation Authority (MRTA). Credit: MRTA

Mountain Rides Transportation Authority (MRTA), which serves the Wood River Valley of Blaine County, Idaho, transitioned to a permanent zero fare transportation program in the autumn of 2020. This decision came in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, which severely impacted transit ridership, and the push to increase mobility across the county. Unlike other transit agencies, MRTA did not complete a pilot and immediately turned to a permanent program to simultaneously increase ridership and access to transportation in the Wood River Valley. In total, MRTA operates paratransit, fixed route transit, and airport shuttle services – all operating zero fare. Like a majority of transit agencies across the US, MRTA has faced a decline in ridership after the pandemic. As MRTA continues to provide services post-pandemic, its permanent zero fare program will require support from both local and state funding sources.

Since implementing zero fare, MRTA has relied on a combination of Federal and Local funding sources for capital and operating expenses. MRTA taps into a diverse range of federal funding mechanisms, including FTA’s Section 5307 (Urbanized Area Formula Grants) and Section 5311 (Rural Area Formula Grants), in addition to the US Department of Transportation (USDOT)’s Better Utilizing Investments to Leverage Development (BUILD) Grant (2025), which supplied $12.5 million for infrastructural improvements. Other significant funding sources include 5311 CARES (COVID-19 relief) funding of just over $1 million, as well as funding to develop a Comprehensive Safety and Action Plan, which allocates $160 thousand for creating and implementing a plan that is aimed at reducing and eliminating serious injuries and fatal crashes affecting roadway users. In addition to federal funds, MRTA depends on local government contributions and partnerships with municipalities in Blaine County. Cities such as Ketchum, Hailey, Sun Valley, and Bellevue provide financial support for the zero fare program through local sales and property taxes.

MRTA’s zero fare program has been performing relatively well with ridership annually in the years following the pandemic. The agency has seen roughly 70% recovery in ridership in 2022 compared to 2019 levels. Building on this success, MRTA hopes to make service improvements with the addition of a new bus depot to support the growing electric bus fleet. Using funding from the State of Idaho in 2022, MRTA became the first transit agency in Idaho to begin fleet electrification.

Even with plans for service improvements and expansion underway, MRTA has faced its fair share of barriers to ensuring the sustainability and success of the zero fare program. Being centrally located in the Wood River Valley of Idaho, MRTA services multiple ski resorts and lodges, thus, their annual ridership peak is in the early portion of the year. Because of this seasonal peak, MRTA only operates a few routes during the peak season. While the seasonal system serves the purpose of getting riders to and from key destinations during peak seasons, it can make year-round commuting difficult for residents who rely on this service to get to and from key destinations all year. From the rider standpoint, seasonal schedules also make it more difficult to bring awareness to the zero fare program, as potential new riders may not have the opportunity to experience the zero fare system. This limited exposure can hinder community acceptance and usage of the program, as people may not see the benefits or understand the service. From an operational standpoint, seasonal schedules may prove difficult in terms of budgeting, and ensuring that drivers are aware that their schedules may have some flexibility off-season.

Moving forward, MRTA is working with the state to procure several new electric buses for both fixed-route service and non-emergency medical transportation. By 2030, MRTA hopes to have an all-electric fleet while reaching new or more riders and offering services with updated vehicles. This change will make MRTA the first transit agency in Idaho with an all-electric fleet of buses. MRTA’s partnership with energy provider, Idaho Power, helped inform the procurement process and assist with planning for electric bus charging and potential grid issues. Further, Idaho Power is helping plan for the new electric bus depot, scheduled to open in the Summer of 2025.

Tribal Transit Example

Auburn, WA – Muckleshoot Tribal Transit Program (MTP)

Figure 12: Tribal Transit Example: Auburn, WA – Muckleshoot Tribal Transit Program (MTP). Credit: Puget Sound Energy

MTP was first launched in 2017 as a Zero Fare Transportation program, serving Muckleshoot Tribe Members as well as the rural-suburban cusp of the greater Auburn and Enumclaw, WA area. The decision to make Muckleshoot Tribal Transit Zero fare was largely influenced by the Muckleshoot Tribe’s commitment to access to transportation and safely expanding access to necessary amenities – jobs, education, and healthcare.

MTP was formed out of necessity for the safety of those without access to a car; safety concerns were brought to light in 2014 as many were seen walking dangerously close to Highway SR 164’s edge, where the speed limit is 55 miles per hour and the shoulder is only 6 inches wide. After three years of planning and procurement, MTP was formed, and zero fare service began immediately. King and Pierce County residents were generally in favor of this program, as it filled a gap in public services and ensured the safety of both Native and Non-Native residents in south King County. Currently, MTP operates two routes between Auburn and Enumclaw using 12-passenger vans. While MTP doesn’t operate its own paratransit service specifically, its non-emergency medical transportation network is ADA-accessible and has the capacity to connect riders to King County paratransit services. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, MTP provided an average of 30 thousand trips per year. In the years following the pandemic, MTP’s ridership has decreased, with just over 2,000 riders in 2020, nearly 7,000 in 2021, and just over 16,000 in 2022.

MTP is mainly funded through local funding and tax revenue, alongside federal grants. In the past, MTP received a large portion of its funding from the Bureau of Indian Affairs and the USDOT. In years past, MTP received formula funding from USDOT’s Ladders of Opportunity Grant, FTA Section 5339 Grants for Buses and Bus Facilities Formula Program Grant, and the FTA Section 5311 Tribal Transit Program Formula Grant, but now primarily relies on local funding to maintain capital and operational funds. More recently, MTP has worked closely with Puget Sound Regional Council to ensure sustainable funding from local sources such as sales tax (0.9% in King County) and property tax. In addition, MTP has worked with private partners for procurement and other capital expenses; for instance, in 2021, MTP worked with private sector company Puget Sound Energy to add electric vehicles to the fleet.

This program has seen an increase in ridership among both Native and Non-Native residents. Post-pandemic ridership recovery is steadily increasing, reaching 54% of 2019’s ridership in 2022, with 2023 and 2024 expected to reach even more passengers than the year before. This increase in passengers can be attributed to MTP’s commitment to service expansion and improving the rider experience. Since MTP’s inception in 2017, steps to improve the passenger experience through surveys, engagement events, and coordination with local planners. System and passenger experience improvements include the addition of passenger counting technology, real-time bus trackers, a website to help familiarize users with the available route, and an increase in service that runs every 30 minutes instead of every hour. Operationally, MTP is working to expand service beyond the single route system that is currently in use and add electric vehicles to the fleet.

While MTP has had its fair share of successes with its zero fare program, it still has many challenges to overcome when planning for service improvements. One of the largest challenges that MTP faces is finding qualified administrative staff to assist with grant writing to maintain their current funding stream, and additional administrative staff to manage service expansion. To help overcome these challenges, MTP is working closely with King County, King County Metro, and Puget Sound Regional Council (PSRC). One of the service improvements that MTP hopes to accomplish is a shuttle service to and from the Muckleshoot Casino but lacks the staff to ensure that this project is a viable option.

Regional (Urban) Example

Research Triangle Region, NC

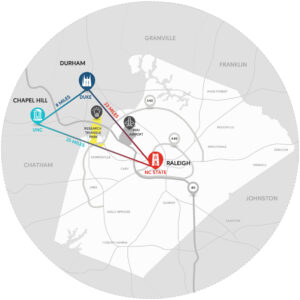

Figure 13: Regional (Urban) Example: Research Triangle, NC – GoRaleigh, GoCary, GoDurham, GoTriangle, and Chapel Hill Transit. Credit: Research Triangle

The Research Triangle region of North Carolina, which includes the Cities of Raleigh, Durham, Cary, and Chapel Hill (see map inset), is served by separate transit agencies, including GoRaleigh, GoDurham, GoCary, and Chapel Hill Transit, which provide urban public transit services within each respective city. GoTriangle, a regional urban transit agency, provides intercity fixed routes, paratransit, and vanpool services. While these agencies are their operating entities, they coordinate branding, schedules, and sometimes fares under the GoTransit brand. These five urban transit systems operate within and across Wake, Durham, and Orange counties.

Wake County and Orange County also operate rural coordinated public and human service transportation services in these areas through GoWake Access Transportation, managed by the Wake County Department of Human Services, and Orange County Public Transportation, managed by the Orange County Department of Transportation. In Wake County, public transit trips within the same city cost $2, while trips to different towns or cities cost $4. Wake County also launched a pilot zero fare microtransit service, GoWake SmartRide NE, available to residents and visitors in northeastern Wake County. In Orange County, fixed route public transit services cost $2 for the general public and $1 for students aged 6-17, with on-demand rides priced at $5 one way.

In addition, North Carolina State University (NC State) in Raleigh offers fixed-route transit services called Wolfline, which operate in and around its campus. The Wolfline service is free and does not require a university ID or any credentials for use. In a similar vein, Duke University in Durham provides a Go Pass that also allows students, faculty, and staff to ride GoDurham, GoTriangle, and GoRaleigh services at no cost.

Some of these transit agencies had been implementing zero fare transportation policies to various degrees and for specific populations for several years prior to the pandemic. For example, all agencies eliminated fixed-route bus fares for children under 18 region-wide beginning in 2018 and expanded the policy for seniors 65 and over in 2019. Additionally, university systems in the region have partnered with related agencies to develop zero fare policies for students (usually paid for in part by tuition fees). In very specific situations, agencies have supported zero fare policies temporarily; for instance, the GoTriangle Board voted to waive fees for unpaid federal employees required to work during a federal government shutdown in 2019.

Chapel Hill Transit is unique as compared to other transit agencies in the region, as it has been completely zero fare since 2002, through a contractual agreement with the Town of Chapel Hill, the Town of Carrboro, and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC). Through this agreement, all partners share operating and capital costs for the transit system. Chapel Hill Transit’s path to eliminating fares included a 2001 analysis of ridership and operating costs. The agency determined that there was about $250,000 in farebox revenue not directly related to UNC transportation, roughly 8% of total system operating costs. Chapel Hill determined that this was a relatively low figure and decided to forgo the revenue to encourage more public transit use in the community. After eliminating fares, Chapel Hill Transit ridership grew dramatically, from about 2.1 million riders between January and September 2001 to more than 3 million riders during the same period in 2002 – a change of about 43%. Before the COVID-19 pandemic, Chapel Hill Transit had an average annual ridership of about 7 million, more than twice as many annual passengers than any other transit system operating zero fare service at that time. The agency emphasizes that the growth in ridership is not only because of the fare policy, but that being zero fare did contribute to the growth of the system through community buy-in and an emphasis on public transit as a community resource.

Figure 14: Regional (Urban) Example: Research Triangle, NC – GoRaleigh, GoCary, GoDurham, GoTriangle, and Chapel Hill Transit. Credit: GoTriangle Transit

In Spring 2020, amid the COVID-19 pandemic, all transit agencies in the Research Triangle suspended fares for riders, utilizing CARES Act relief funds to offset revenue loss. During the four-year zero fare period, transit operators and transit advocacy groups praised these policies for making transit in the region more accessible and reducing contact between transit operators and the public during the COVID-19 pandemic.

In May 2022, GoRaleigh published a fare analysis to evaluate the change to zero fare service. Though the report only concerns one transit agency in the region, it highlights the impacts that zero fare policies can have on riders, particularly minority and low-income riders. The report notes that under the previous system with fares, “minority and low-income riders were paying for the most expensive fare types at a rate higher than the system average and were benefiting from discounted and free fares at a rate lower than the system average.” Ultimately, the fare analysis determined that the “impacts of fare free transit are positive and benefit all riders.”

While the impacts of removing fares on ridership are difficult to determine given the massive overall decrease in ridership due to the COVID-19 pandemic, GoRaleigh retained a higher percentage of ridership than other similar transit agencies, due in part to its zero fare policy.

Despite these benefits, the suspension of fares was intended as a temporary measure. Once funding through the CARES Act was no longer available to help fill the agency’s financial gap, Raleigh City Council voted to resume collecting fares in July 2024. Opinions on this decision were divided both for members of the public and the GoRaleigh Board. While proponents of the decision cited safety on buses as a concern that fares would address, others believed that reinstating fares could open the door for potential conflicts with drivers enforcing the policy. Additionally, fare revenue would make up an estimated 2% of the system’s operating budget, and would do little to address the agency’s anticipated $8.2 million deficit. During a public hearing about the decision in May 2024, about ⅔ of comments from members of the public opposed reinstating fares.

Other transit agencies in the Research Triangle are also in the process of reinstating fares, with the exception of Chapel Hill Transit, which will remain at zero fare per its previous policy. GoTriangle joined GoRaleigh in collecting fares in the Summer of 2024, and GoCary and GoDurham will continue to suspend fares through June 2025. The decision to return to collecting fares for these agencies came with other changes to mitigate the impacts of fares for low-income riders. Concurrently with reinstating fares, GoRaleigh and GoTriangle adopted a new account-based mobile ticketing platform through technology partner Umo, which also allows for closed-loop contactless payments on buses and fare capping. The new platform aims to facilitate better coordination between agencies, as payments on either GoTriangle or GoRaleigh buses will apply towards a single fare cap. GoTriangle also simultaneously launched the GoPass, offering discounted fares for youth, seniors, and individuals with disabilities or low income, allowing them to enroll for reduced transit fares. There is currently no charge to transfer from a GoTriangle bus to a GoRaleigh bus, but there is a $1.25 upcharge to transfer from a GoRaleigh bus to a GoTriangle bus. GoDurham, GoCary, and Chapel Hill Transit are also included on the Umo app for trip planning purposes, even though there is currently no payment necessary.

Chapel Hill Transit Spotlight

Figure 15: Regional (Urban) Example: Chapel Hill Transit bus riders. Credit: Chapel Hill Transit

Chapel Hill Transit (CHT) stands out in the Research Triangle region of North Carolina for its zero fare program, launched in 2002. CHT is a municipal transit agency funded through a partnership between the towns of Chapel Hill and Carrboro, the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC), which is the largest financial contributor, providing 31% of CHT’s operating revenue of the adopted 2024-2025 budget.

The zero fare initiative was developed in response to increased development in the early to mid-90s, which expanded UNC’s campus and increased the population in the area. It also promotes multi-modal transportation options and reduces barriers to essential services like employment, grocery stores, and healthcare.

Collaboration between the university and the town has been crucial for the zero fare program, emphasizing a shared commitment to effective transit solutions. The community has long supported transit services, aligning with CHT goals to enhance public transportation over car-centric initiatives such as widening streets or building more parking facilities. During financial struggles, the student senate at UNC encouraged students to start taxing themselves a transportation fee to help pay for CHT, eventually leading the university and town to provide additional funding to support CHT’s operations