The Role of Data Specifications in Creating an Interoperable Transportation System

20 minutes Author: Shared-Use Mobility Center Date Launched/Enacted: May 11, 2021 Date Published: January 13, 2025

Brief Summary

- Data specifications are the prescriptions or outlines for how data should be conveyed between parties. They provide a common language for how transportation services share information with each other and with users.

- Some commonly known transportation data specifications include the General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS), the General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS), and the Mobility Data Specification (MDS).

- People interact with data specifications in action in their daily lives. For example, the Google Maps app uses GTFS when used to search for directions on public transit.

- Data specifications can positively impact how people access information about shared mobility services, like schedules, routes, stops, and fares.

Introduction

In this digitally powered mobile age, transportation providers have to share data across multiple applications and tools with regulators and other government entities. This is crucial for enabling travelers to plan trips and for cities to understand transportation needs. Moreover, with the widening scope of mobility apps like Google Maps, Apple Maps, Transit, and Moovit, it is increasingly important to share service information in ways that can be readily interpreted by a variety of platforms.

Data specifications and standards are fundamental in this process. They establish reliable, agreed-upon frameworks for communicating and exchanging transportation data. In public transportation and shared mobility settings, these data carry information like routes, stops, schedules, and fares, and regulatory information like parking rules or operational areas. This case study provides an overview of major transportation data specifications and standards and how they can be useful to professionals across the transit and shared mobility industries. For mobility service providers, in particular, it provides resources that can help you make data more readily available for agencies and the public and allow for the integration of services.

Questions and Answers

Before exploring some of the existing and developing data specifications and standards in the transportation field, it is important to understand some key terms and concepts:

1. What is the difference between a data specification and a standard and why do they matter?

A specification is a prescription or outline for how data should be conveyed between parties. For example, the Transactional Data Specification, which will be explored in greater detail later in this case study, suggests a format in which data from a mobility provider should be presented to facilitate information exchange to help with booking and scheduling. When a specification becomes more widely adopted or is endorsed by an industry, it becomes a standard overseen by a governing organization.  In other words, if enough entities use a data specification, it becomes a standard, allowing for the broader adoption of multimodal integration and enhanced awareness of mobility options for travelers. The difference between data specifications and standards is explored further in Modernizing Demand-Responsive Transportation for the Age of New Mobility (2020). In short, all data standards are specifications but not all specifications are standards.

In other words, if enough entities use a data specification, it becomes a standard, allowing for the broader adoption of multimodal integration and enhanced awareness of mobility options for travelers. The difference between data specifications and standards is explored further in Modernizing Demand-Responsive Transportation for the Age of New Mobility (2020). In short, all data standards are specifications but not all specifications are standards.

2. What types of transportation data specifications exist?

In the transportation field, there are many specifications that exist in various stages of development. These specifications often fall within three categories: discovery, transactional, and operations.

Roger Teal et al. concisely outline discovery and transactional data specifications in Development of Transactional Data Specifications for Demand-Responsive Transportation (2020): “Discovery data is information about what services exist, their configuration, and possibly their current status, for example, ‘The next bus on Route 12 arrives at Elm Street at 9:35 AM.’ In contrast, transactional data includes all the information travelers need to actually book and schedule a specific trip, including payment information (p.32).”

Operations specifications deal with data about the management and maintenance details of transit services, and are geared towards transit providers or policy makers rather than end users. For instance, the Mobility Data Specification provides a structure to communicate service and regulatory data primarily between cities and private micromobility providers.

3. What is an open vs. closed data architecture?

Since data specifications and standards serve as templates for stakeholders in the transportation industry, they must have an open architecture so that providers can develop and present data in a common format across platforms. An open architecture is “a technology infrastructure with specifications that are public as opposed to proprietary”. Many technology companies, such as transportation network companies or microtransit operators, present their own information to users through a closed and proprietary architecture, which are sometimes referred to as “walled gardens.”

An open data architecture allows, among other things, third parties to interpret and present the data into their own or other platforms. While this will be explored later in greater detail, it is important to note that data are often made publicly available on a transportation provider’s website. This allows developers and members of the public to quickly access an agency’s or company’s information so that they can use it readily in their applications or analysis. On top of this, data specifications should have a governance plan and be flexible and iterative—as needs change and new technologies enhance the ability to exchange information, specifications need to be updated or replaced. Adaptable and iterative specifications help transportation service agencies provide the most useful and current information to developers and ultimately, its users.

4. Who oversees the development and operation of data specifications and standards?

Typically, when data specifications are in the process of being designed, professional communities and industry working groups collaborate and determine the need of said specifications. In order for a data specification to be widely adopted it needs a governance model to oversee and facilitate their continued development. For example, MobilityData oversees the General Transit Feed Specification and General Bikeshare Feed Specification, while the Open Mobility Foundation oversees the Mobility Data Specification. These governing organizations can serve as valuable resources in accessing information about data standards and the people in their respective communities.

GTFS Schedule and Realtime data can be easily accessed through Community Transit’s website.

Click on image for full view.

Credit: Community Transit (https://www.communitytransit.org/opendata)

5. Why are data specifications relevant for me?

Whether you work at a transportation network company, a micromobility provider, or a transit agency, data specifications can help you to understand and relay accurate information to users, vendors, and stakeholders. Much like a coding language, they are accessible, well documented, and commonly understood tools that create a connected and efficient mobility network.

6. Can data specifications support access?

Data specifications have helped to make public transit and shared mobility more user friendly and transparent. Some data specifications have made information for public transit and shared mobility accessible through our phones and computers. Before these data specifications, people relied on analog modes, like timetables, to determine which buses and trains to use. As a result, people would not know if public transportation was off schedule or if any bikes were available at a nearby docking station.

Data specifications also give transit agencies and mobility companies formats in which to present their information, like regulations, routes, stops, and location of vehicles to customers and policymakers. New tools and technologies have come about alongside the development of these specifications that help agencies and other transportation providers translate complicated information into more outlined formats. With specifications, transportation providers of different sizes and resources have the ability to better communicate information to their customers, making transportation services more accessible to everyone. Some of these resources are explored in other sections of this paper.

However, while specifications can help to improve mobility options, there are some important barriers to their adoption. Specifications in early development might overlap in their purpose as they are typically overseen by volunteer steering committees of transportation professionals, who may not know the industry as a whole. While this can lead to fragmented work, it also presents an opportunity to harmonize efforts towards data standardization.

The processes to develop specifications that are adopted by the broader transportation industry can be both lengthy and costly. It is an iterative process, which involves active demonstration projects to test and refine the data specification in real transit user situations. On top of this, in order to realize the user benefits, customers of transportation providers need to have access to technologies like smartphones. Moreover, basing mobility planning decisions solely on data without checks and balances nor understanding how the data are maintained and audited can have implications if the data are biased and do not portray what is really happening on the ground.

7. I’m overwhelmed. I don’t know where to start with data specifications and all of this is new to me. I don’t have the capacity to translate my transportation data into some other format.

Good news! Many of the data specifications have budding or strong communities that support them. Currently, there are many low-cost or free tools that can help you translate your data so that it will be more useful to transit agencies, private shared mobility operators, app developers and more importantly, transit users. State Departments of Transportation might also have resources to support the technology needs and financial costs of implementing data specifications, particularly with smaller transit agencies.

Often, a good time to begin working with open-data solutions is when an agency procures or renews mobility contracts. The Mobility Data Interoperability Principles (MDIP), a coalition of government agencies, mobility service providers, and nonprofit organizations, outlines five principles to help the industry navigate toward an interoperable future. MDIP also maintains data specification procurement guidelines to help agencies understand when and how to include interoperable data in the procurement process. For more information on interoperability and why it should be included in the procurement process see the The Path to Mobility Interoperability Logic Model. Considerations for moving data specifications forward are outlined in the Connecting Communities Roadmap and Implementation Guide. Key categories begin with planning, design, implementation, and refinement. Interagency partnerships, engaging the community, and active governance oversight are central to the process and must be revisited throughout.

Let’s explore some of these data specifications and the tools and resources that you can access.

Table: Some Commonly Known Transportation Data Specifications

| Specification | What it does |

Resources | Governance Structure | Where it’s deployed |

| General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) | Specifies the format to display static data for fixed route service, such as schedules, stops, and fares for use by app developers and the broader public. | Overseen by MobilityData. | Over 10,000 transit agencies in over 100 countries. | |

| GTFS-Realtime | Realtime is a feed specification that allows public transportation agencies to provide real-time updates about their fleet, including trip updates, service alerts, and vehicle positions. | Overseen by MobilityData | Widely used by transit agencies. | |

| GTFS-Flex | Accounts for Demand-Responsive Transportation (DRT) services. | Overseen by MobilityData. | Statewide examples include the Minnesota Department of Transportation, Michigan Department of Transportation, and more locally Hopelink Find a Ride transportation services based in Seattle, Washington. | |

| General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) | Specifies the format in which micromobility providers should publicly present service information, including vehicle and dock location and availability. | Overseen by MobilityData in partnership with The North American Bikeshare and Scootershare Association (NABSA). | Widely used by micromobility providers across the US and internationally. | |

| Mobility Data Specification (MDS) | Outlines a structure for mobility providers and jurisdictions to securely communicate trip, vehicle, service, and regulatory data. In contrast to GBFS (which is included as a public-facing subset of what MDS provides), the raw data is not intended for consumption by the public or mobility apps. | Overseen by Open Mobility Foundation. | More than 130 cities internationally. | |

| Transactional Data Specification (TDS) | Outlines a structure for DRT scheduling and booking transactional data. |

|

In the working group phase. | A handful of demonstration projects in the US are underway. |

| Transport Operator Mobility-as-a-service Provider (TOMP) API | The TOMP-API is an interoperable open standard for technical communication between Transport Operators and Mobility as a Service (MaaS) Providers. | In the working group phase with a handful of demonstration projects underway. | TOMP-API originated in the Netherlands and is currently in use by several programs in Europe and Australia. There is interest in the US to look at its potential applications. | |

| CurbLR | Communicates curb-use regulations from local governments to mobility, delivery, and freight services and the broader public. | Overseen by SharedStreets. | Demonstration projects underway. | |

| Curb Data Specification (CDS) | Provides a framework for communicating regulations between local governments, mobility, delivery, and freight services and the broader public. | Overseen by Open Mobility Foundation. | Over two dozen cities and companies. | |

| Transit Operational Data Standard (TODS) | Outlines the “behind the scenes” operational information needed to provide transit service. TODS extends GTFS to define additional operational details that may be helpful to transit operators, like deadhead time. | MobilityData serves as the TODS Manager under the authority of the TODS Board. | — | |

| Transit ITS Data Exchange Specification (TIDES) | Offers a standard data structure for accessing and managing archived and historical intelligent transportation systems (ITS) data relating to transit operations datasets like vehicle location, passenger counts, and fare transaction data. | Managed by MobilityData. Governed by a Board of Directors consisting of representatives from transit agencies and other public and private stakeholders. | Various transit agencies throughout the US, including WMATA, which received a $2 million Strengthening Mobility and Revolutionizing Transportation (SMART) grant from the US Department of Transportation in 2022 to develop and pilot a TIDES platform. |

Overview of Specifications

General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS)

The General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS) is among the most widely used transportation data standards. Established in 2006 as a collaboration between Google and TriMet in Portland, Oregon, GTFS is a tool for transit agencies to communicate fixed route transit service information to the public. As an open data standard, GTFS allows for the communication of fixed route transit service in a format that can be commonly understood and consumed by rider-facing software apps. Today, thousands of transit agencies across the globe use GTFS to provide information to customers through apps like Google Maps, Moovit, TransitScreen, and Transit.

The primary component of GTFS consists of a group of comma-delimited text files that together provide static, infrequently changed information on items like stop locations, routes, schedules, and fares. GTFS has a strong community supporting its continued development and is governed by the non-profit organization MobilityData.

Since 2023, the Federal Transit Administration has required that all transit agencies in the US that operate fixed-route service must maintain and submit a GTFS dataset to the National Transit Database. This data helped build the National Transit Map, supports trip planning for transit users, and standardizes information collection on routes and schedules. Because GTFS is such a widely used standard, many resources are available to help transit agency staff develop their own GTFS feeds. Some examples include::

- GTFS.org (maintained by MobilityData)

- Google’s GitHub repository for GTFS

- National RTAP’s GTFS Builder

- Trillium GTFS Manager

- World Bank Group Online Self-Paced Course on GTFS

GTFS Realtime

GTFS Realtime extension describes dynamic information like vehicle locations, delays, arrival times, and station closures. Trip-planning apps can interpret and display real-time fixed-route service data, which is particularly useful for transit users so they can track their bus or train in real time to better plan their trip and transit connections.

GTFS-Realtime resources include:

- GTFS Realtime – General Transit Feed Specification

- GTFS Realtime Overview | Realtime Transit | Google for Developers

- GTFS.org

GTFS-Flex

GTFS-Flex outlines a framework for communicating DRT service area boundaries and on-demand flexible trips, including booking rules and actions for more individualized service types, such as: dial-a-ride service, route deviation service, and point-to-zone service.

An example of GTFS-Flex in action is the Minnesota Department of Transportation’s (MnDOT) regional trip planning platform, supported by FTA innovation grants and hosted through the Transit App. The platform incorporates GTFS and GTFS-Flex to allow customers in southern and western Minnesota to discover, book, and pay for various shared mobility services (payment is handled outside of GTFS and GTFS-Flex). The demonstration project helps partner agencies develop and maintain their own GTFS and GTFS-Flex data feeds, which can sometimes be a challenge for small and rural agencies due to technical and staff capacity. GTFS-flex was officially adopted into GTFS in March, 2024.

Below are some other helpful resources to learn more about GTFS-Flex:

- GTFS-Flex is Officially Adopted: Everything You Need To Know

- GitHub repository for GTFS-Flex

- Trillium and the National Center for Applied Transit Technology (N-CATT): “GTFS Flex – What Is It and How Is It Used?”

GTFS Extensions

There are many other existing and proposed extensions to GTFS. These extensions are often focused on providing information on more specific aspects of transportation services, such as specialized transportation through GTFS-Eligibilities (rider transportation needs) and GTFS-Capabilities (vehicle type and amenities), GTFS-RT-OccupancyStatus (occupancy and crowding), GTFS-Pathways (station characteristics and accessibility), GTFS-FareProducts (fare and payment information). MobilityData provides an overview of existing and proposed extensions on their site.

General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS)

The General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) is the most established transportation data specification for micromobility services. Since its adoption in 2015, GBFS is widely used in the US and internationally to display bikeshare and scooter data, providing information to assist in micromobility operations and important information to users to access the system. GBFS has a strong community and is overseen by a consensus-based governance model.

GBFS was founded in 2014 by Mitch Vars of Nice Ride Minnesota, and gained the endorsement of NABSA the following year. It is important to note that GBFS data only includes information on the availability of micromobility vehicles or docks, and not routes, users, or locations during trips. This is intended to protect the privacy of vehicle users, such as their location when borrowing vehicles or their trip history. Because micromobility vehicles are used by individuals, GBFS has to account for the privacy of individuals in its design, unlike GTFS.

Like GTFS, GBFS has assumed the identity of a transportation data standard and has a strong governance structure. Today, GBFS is also overseen by MobilityData, in partnership with NABSA. Below are helpful resources for those interested in GBFS and the community that surrounds it:

- NABSA: Data Good Practices for Municipalities: Understanding the General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS)

- MobilityData GBFS Resource Center

- NABSA: “GBFS & Open Data”

- GitHub repository for GBFS

- GBFS Slack Channel

Mobility Data Specification (MDS)

Like GBFS, the Mobility Data Specification (MDS) is also intended for use by micromobility providers but is intended to inform policymakers, planners, micromobility providers, and regulators. More specifically, MDS is a two-way conduit of information which includes information from both operator and jurisdiction and it tracks individual vehicles, whereas GBFS helps customers get information on vehicles that are only available for rent. MDS was proposed originally by the Los Angeles Department of Transportation and tested for the first time in 2018. MDS is currently governed by the Open Mobility Foundation. Micromobility providers and regulators can use MDS to provide and obtain information on issues like ensuring compliance with device caps and seeing what vehicles are in operation.

Helpful resources on MDS:

- Open Mobility Foundation’s GitHub repository for MDS

- Shared-Use Mobility Center: “Mobility Data Specification: A Data Standard for Shared Mobility Providers, Los Angeles, California, 2018”

Transactional Data Specification (TDS)

Human services transportation typically takes the form of what is called demand-responsive transportation (DRT) — services that do not follow fixed routes or schedules. There are an estimated 1,000 DRT services currently operating in the U.S., many of which are in rural communities.

DRT services are critical for people who cannot drive or access regular public transportation, but they are often fragmented. There may be multiple providers in a given region, but each may operate in a silo, leading to duplicative services and denials of trip requests.

The Transactional Data Specification (TDS) sets out to address the transactional details needed to schedule a trip for DRT services like paratransit and microtransit. TDS complements discovery specification tools by providing the information needed for scheduling and booking DRT services. TDS is being tested by a handful of demonstration projects in the US.

A more widely adopted TDS could help shared-mobility providers and transit agencies across the United States and elsewhere more easily share trip information.

Following are some TDS resources to understand its applications:

- SUMC: Connecting Community Transportation: Lessons Learned from Transactional Data Specification Demonstration Projects and supporting Roadmap for TDS Implementation

- Jana Lynott, AARP: “Modernizing Demand-Responsive Transportation for the Age of New Mobility”

- Roger Teal et al: “Development of Transactional Data Specifications for Demand-Responsive Transportation”

- AARP: FlexDanmark Video Series

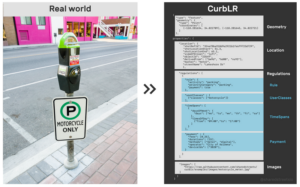

CurbLR

Compared to the other data specifications featured in this case study, CurbLR is unique in that it outlines how information on curb space and curb regulations should be made available, as opposed to information on networks for transit and shared-mobility services. Curb management plays an important role for stakeholders, such as micromobility operators, parking technology companies, ridehailing programs, and municipal agencies. An example application of CurbLR was piloted in Philadelphia in 2020 to understand how curb management affects traffic. CurbLR is primarily intended for use by city agencies and regulators, like MDS, and is composed of GeoJSON files.

Compiled below are some resources for those seeking to learn more about CurbLR:

- CurbLR.org

- SharedStreets: “CurbLR”

- GitHub repository for CurbLR

- SharedStreets: “Towards a Data Standard for Curb Regulations”

Image of how a parking meter is translated into CurbLR information

Click on image for full view.

Credit: CurbLR GitHub Page (https://github.com/curblr/curblr-spec)

Curb Data Specification (CDS)

An increasing demand for sharing information on curb regulations has also resulted in the creation of the Curb Data Specification (CDS). The Open Mobility Foundation first announced the release of the initial candidate for CDS in 2022, which is meant to be a communication tool between municipal agencies and mobility providers like taxi and delivery companies. A CDS feed is composed of three application programming interfaces (APIs): a Curbs API, an Events API, and a Metrics API.

Existing resources on CDS include:

Transit Operational Data Standard (TODS)

The Transit Operational Data Standard is designed to assist transit providers with “behind the scenes” information needed to provide service to riders, such as vehicle routes, vehicle operators, shift start/end times, and service disruptions. This information is critical to transit operations but it is often fragmented across proprietary formats maintained by scheduling and CAD/AVL companies. Cal-ITP created the TODS standard to address this gap and improve communications across data sources.

To learn more about TODS, visit these resources:

Transit Operational Data Standard Working Group. 2022. Transit Operational Data Standard. Transit Operational Data Standard Board of Directors. https://ods.calitp.org.

Transit ITS Data Exchange Specification (TIDES)

Intelligent transportation systems (ITS) are applications that use advanced technologies and information to improve transportation services. ITS data, including vehicle location data, passenger count data, and fare transaction data, is used widely in service planning and operations. Archived ITS data in particular is valuable for transit planning, but this data is often difficult for agencies to access and use effectively, particularly due to large data sets, poor data quality, poor integration with other data, and barriers to data sharing between different technology vendors. The Transit ITS Data Exchange Specification (TIDES) aims to address these challenges by establishing a framework for agencies to collect, store, and manage historical ITS operational data. TIDES can support transit agencies that face difficulties accessing or using archived ITS data by simplifying this data and making it accessible, usable, and shareable to better inform transit planning and decision making.

Transport Operator Mobility-as-a-service Provider (TOMP) API

Summary coming soon.

Conclusion

This paper provides an overview of some of the data specifications and standards that are being tested and used for public transit and shared-mobility services. Many of the specifications listed above shape the public’s relationship with transit and shared mobility. Because of GBFS and GTFS, people across the world can readily access information about their transportation options in seconds. Moreover, they have given developers the opportunity to experiment with creative ways to provide new types of information to users of transit and shared mobility, which can support accessibility and safety. In this regard, specifications are laying an important foundation for MaaS.

Challenges exist, however, in that specifications for DRT, like TDS have not been widely accepted by the industry. In addition, learning and technical barriers often prevent the development of feeds depending on the resources, staffing, and institutional knowledge within a transit agency or organization. To address this challenge, states like California compel transit agencies to develop GTFS feeds through offering Minimum GTFS Guidelines, developed by Cal-ITP.

Some mobility providers and transportation network companies have created “walled gardens,” preventing transit agencies and the broader public from accessing their data. This is a widespread obstacle to fully integrating services so they serve the most public good. At this time, some of these proprietary technology platforms are working to figure out how to share or adapt their information. If more widely utilized, these data specifications and standards have the potential to break down these walled gardens and promote a more seamless transportation experience to users by fostering communication across platforms. This could be a significant breakthrough—especially for marginalized communities, people with disabilities, and older adults.

Broadly implemented data specifications and standards are fundamental in enabling and enhancing the MaaS experience. From creating new specifications to updating existing ones to further serve changing needs, these tools are vital in creating interoperable transportation networks.

Originally Published January 12, 2025, Revised March 2025.