Zero-Fare Transit

20 minutes Author: Shared-Use Mobility Center Date Launched/Enacted: Jul 5, 2022 Date Published: December 19, 2022

To see the most recent updates on the zero fare industry, please visit our updated 2024 case study.

Brief Summary:

- Zero-fare transit continues to be under consideration as agencies assess how to best meet their agency and users’ needs.

- Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, the zero-fare approach arose as a way to improve the quality of life of public transit users. Those initial motivations remain instrumental, but in the Covid-19 context, zero-fare also allowed agencies to ensure safety and security for operators and riders.

- Eliminating fare collection can result in advantages related to cost, system efficiency, access, and operations. However, it can also present challenges. Because switching to zero-fare transit will impact agencies differently, it is important to examine organizational capabilities ahead of time and listen to community input.

- Since a loss of farebox revenue could result in service cuts or serious financial challenges, agencies are examining alternative fare policies, such as fare-capping.

Introduction

For several years, zero-fare transit has been a topic of interest among public transportation agencies. Many of the arguments for zero-fare transit–and barriers to its implementation–were made even more compelling by the ridership impacts brought by the Covid-19 pandemic. Service changes and policy and funding flexibility at the height of the pandemic not only allowed for experiments in fare collection, they also presented an opportunity for agencies to reevaluate the underpinnings of fare policies and the cost of collection processes. As the pandemic and the widespread changes it catalyzed in travel patterns continue to reshape public transportation services and operations, agencies are assessing how zero-fare or alternative fare structures can be leveraged to reduce mobility inequities, increase ridership, improve boarding procedures, decrease the potential of fare related conflicts, and eliminate many costs and staffing burdens associated with fare collection.

While zero-fare has the potential to bring improvements to operational, affordability, and equity aspects of a transit system, it can have downsides as well. This case study highlights several agencies’ experiments with zero-fare transit, delving into their motivations, goals, and outcomes. It also provides a set of key considerations for other agencies exploring such changes for themselves.

Why Agencies Are Considering Zero-Fare Transit

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced a reckoning in how public transportation service is provided and perceived. Very soon after the pandemic began, many agencies went zero-fare as a means of promoting social distancing in transit vehicles. At the same time, the pandemic prompted a transformation in how people view and understand the value of public transportation as an essential service, catalyzing additional conversation around fares.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, zero-fare transit service arose as a method to expand equitable access to public transit, foster transit ridership, and reduce household transportation costs. Many of those initial motivations remain instrumental, but in the Covid-19 context, eliminating fares also allowed agencies to ensure safety and security for system users, minimizing interaction between operators and riders and providing relief for many individuals depending on transit as their main mode of transportation.

Zero-fare continues to be under consideration as more agencies assess how to best meet their agency and users’ needs. For some, the expenses associated with fare collection, including the investment in technological hardware to collect fares, staffing resources to manage and count fares, and longer dwell time, inspire the search for improvements or alternatives to current fare structures. For others, the emphasis on transit to address social justice and equity concerns is a key consideration in experimenting with a zero-fare approach.

What is Zero-Fare Transit?

Zero-fare systems refer to agencies that have removed transit fares paid by individual riders and replaced farebox revenue with funds generated through other avenues such as local taxes and public-private partnerships. These systems have been viewed as a step toward more equitable and just mobility for all because they remove access barriers and shape transit as a social right. Fares can be seen as a regressive tax that places a disproportionate burden on low-income populations. This is because low-income populations dedicate a higher proportion of their earnings towards transit compared to higher-income populations, despite their greater reliance on the service [1]. Zero-fare looks to minimize their financial burden and increase access to transit. Still, going zero-fare can be a challenge for financially-strapped agencies and should not be viewed as the answer to all problems.

Credit: The Boston Globe

Many agencies are straying away from using the term “fare-free” as it dismisses the complexities in which transit operates. Nothing is free, however, in a zero-fare system, monies from fares are re-allocated and replaced with other non-fare revenues to remove the financial burden on users. Under zero-fare, rides are free to the user, but revenue is still needed to support the overall operation of transit services. To fully eliminate fares, agencies need to come up with revenue previously covered by fare collection. Therefore, agencies usually decide between two funding scenarios: they either operate with a new dedicated public funding source like a tax, or take on alternative measures to bridge budget shortfalls. Either scenario relies on continual investment by the community, partner institutions, or government.

Zero-fare transit has taken many forms over the years, with some agencies opting to take more of a hybrid approach. For instance, rather than go completely zero-fare, the Utah Transit Authority has adopted a partial zero-fare structure in which passengers can ride free on buses in dedicated zones. In this case, there is an expectation that passengers pay for service once the bus leaves the geographic boundaries of the zero-fare zone. Other agencies, like Alameda County Transportation Commission, have established zero-fare pass programs that allow certain population groups to ride transit without paying a fee. While characterized by their differences, these approaches still have one thing in common: they advocate for better access to transportation.

History of Zero-Fare

Zero-fare transit programs in the United States date back to the 1960s when small urban cities, like Commerce, California, began implementing “free” transit services [2]. Since then, varying levels of zero-fare transit services and initiatives have sprouted throughout the United States.

Typically, zero-fare systems have operated in small urban areas, resort towns, and university communities because of their rider characteristics and relationships with funding. In recent years, zero-fare transit has started to gain momentum across the United States as more people recognize transit’s role in a functioning and equitable society.

Established Zero-Fare Transit Pilots and Programs

It can be difficult to fully realize the impacts zero-fare policy brings to transit systems that have suspended fare collection during the pandemic. Zero-fare transit pilots and programs established before the pandemic can help us understand its impact.

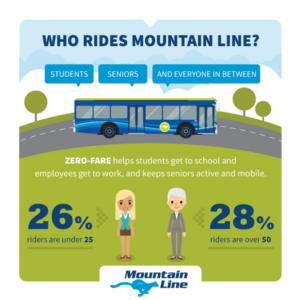

Mountain Line Transit, the main public transportation provider throughout Missoula, Montana, and the surrounding area debuted zero-fare in January 2015 as a system-wide three-year demonstration project. The program was initially funded through public-private partnership monies and has since received voter-approved funding to make zero-fare permanent. Service improvements were rolled out at the same time as the zero-fare program, but Mountain Line has attributed much of its success over the past few years to eliminating user fares.

The zero-fare program has eliminated the need for onboard fare collection and associated administrative costs, offering the agency more flexibility with their funding and increased efficiency along routes. In addition, increases in ridership led the agency to apply for and secure federal grant funds that have contributed to bus stop improvements and the electrification of their vehicle fleet. In 2018, Mountain Line received a Low-No Emissions Vehicle grant and Bus and Bus Facilities grant from the Federal Transit Administration (FTA) partly due to their 70% ridership increase between 2015 and 2018.

Credit: Mountain Line

Mountain Line Transit’s initial motivation behind the zero-fare project was community requests; however, this varies among agencies. Chapel Hill Transit (CHT), a provider of zero-fare transit services since 2002, felt foregoing fares could bring significant savings in program administration. For CHT, a zero-fare system would eliminate tedious administrative tasks for the University of North Carolina as well as the need to purchase additional farebox equipment compatible with student IDs [3]. Contributions from major key players like the university and its health care system made zero-fare transit possible. Since implementation, ridership has increased from just under 3 million riders in 2002 to nearly 7 million riders in 2019 just before Covid-19 [4] [5]. While the system’s successes are not exclusively due to zero-fare, Chapel Hill’s Transit Director Brian Litchfield believes this decision paved the way for a better system in the long term. In an interview with Chapelboro.com, Litchfield also indicated that commitment and interest from the town of Chapel Hill, the town of Carrboro, and UNC at Chapel Hill was integral to pursuing zero-fare in the first place [6].

Commitment from community partners has also played an integral role in the pursuance of zero-fare for agencies like Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA). KCATA began phasing in zero-fare in 2017 for certain groups before transitioning to a fully zero-fare system in March 2020 in metropolitan Kansas City. Because of zero-fare buy-in from partners like Blue KC, the agency offers better access to vital community services, food, medical, and employment opportunities improving residents’ quality of life. Although the presence of disruptive passengers has challenged some agencies that have implemented zero-fare policy, the number of disputes on KCATA routes has decreased since zero-fare adoption. Before the switch, around 85% of incidents were over the need to pay fares.

Because of its rather large service area and operations, KCATA needed to find replacement revenue to support continued service under a zero-fare policy. KCATA made up the missing revenue through investment from the Kansas City, Missouri City Council and cuts in management costs. For Kansas City, the costs to insert new fareboxes, collect and maintain fare collection systems, and transport the money were so great that removing farebox revenue allowed them to save nearly $1 million a year [7]. Similarly, Intercity Transit in Olympia, Washington, also found that eliminating fareboxes saved money in the long term because of expenses associated with upgrading payment systems.

Nevertheless, cost savings is not always feasible for all agencies. In some cases, agencies that previously adopted a zero-fare structure had to revert to charging fares because of funding shortfalls. For instance, Link Transit in Washington State operated as a zero-fare system from 1989 until 2001, when a statewide vote that eliminated the motor vehicle excise tax resulted in Link Transit losing 45% of its operating revenue [8]. To navigate the newfound budget constraints, Link Transit reinstated fares to sustain as much of their previous service as possible. Although Link Transit has re-established a zero-fare program during the pandemic, history shows that fare revenue can be a substantial supporter of transit operations for some agencies.

Credit: Rhode Island Public Transit Authority

Lastly, with the knowledge that dedicated revenue streams build sustainable public transportation services, entities are finding new ways to promote public transportation and form funding partnerships. Thanks to an Accelerating Innovative Mobility grant award by the FTA, the Rhode Island Public Transit Authority (RIPTA) is incorporating zero-fare and technology into a project which could pave the way for targeted partnerships. In 2020, RIPTA used the AIM funding to jumpstart their “Ride Free in Central Falls” program, a year-long initiative that uses geofencing technology to enable free transit rides for individuals who use farecards and board within the City of Central Falls’ boundary. Ridership and other data collected will inform future fare incentive programs and transit policy on a local and national level. Ultimately, the use of geofencing technology may prompt certain entities, like social service agencies, to sponsor ridership in areas of interest, leading to new funding streams.

Zero-Fare Transit Pilots during the Covid-19 Pandemic

During the Covid-19 pandemic, the federal government established emergency relief funding programs to support transit agencies in their attempt to alleviate system strain and maintain essential mobility functions in America’s communities. While some agencies contemplated zero-fare before the pandemic, the establishment of federal assistance programs and the need to quickly adapt to social distancing scenarios made it a reality. Transit agencies across the country could suspend fare collection because of the support they received through the American Rescue Act, CARES Act, and other federal relief programs.

Over the past two years, cities and transit leaders have either developed new pilot programs, extended current zero-fare programming, or taken on an alternative fare structure to better support their customers. DASH in Alexandria, Virginia and ABQ RIDE in Albuquerque, New Mexico used zero-fare’s momentum to remove fares across all of their transit services. Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA) took a different approach, establishing a Boston pilot program that offers zero-fare bus service on certain routes that travel through communities hit hardest by Covid-19.

Credit: The Boston Herald

In a time of financial stress, eliminating fares meant individuals could redirect the money they were using for transportation to other crucial expenses, goods, and services. Agencies, such as North Carolina’s GoTriangle, who have continued fare suspension with federal assistance, hope that doing so will continue to support current system users in their daily lives and attract new riders to the system.

Despite federal funds supporting agencies’ zero-fare extensions and pilots, there are still looming concerns over the long-term fiscal sustainability of zero-fare structures. In some instances, the extension of zero-fare programming means buying more time to figure out next steps after federal relief funding ends. Worcester Regional Transit Authority plans to use its one-year extension of its zero-fare policy to develop a more sustainable fare policy for the longer term.

Agencies Studying Zero-Fare Transit

Of the many transit agencies that have gone zero-fare due to the pandemic and its associated impacts, some agencies are still questioning whether permanent implementation or continued sustainability of zero-fare programming will put their agency on a successful course moving forward. Covid-19 has accelerated the transition to zero-fare and challenged local policymakers to determine the future of zero-fare programming in their respective areas. Should an agency remain zero-fare, transition back to their previous fare system, or pursue other fare payment opportunities?

To address these questions, agencies are reviewing the feasibility of going zero-fare long term. In fall 2020, LA Metro undertook an exploratory study to understand the implications of a fareless system on equity, safety, ridership, operations, access, and funding streams. Through coordination and evaluation of the study’s findings, the Fareless System Initiative Task Force developed strategic recommendations, which led to board approval of a zero-fare pilot program in 2021. While the pilot program will not address all population groups, K-12 and community college students of all incomes will be able to ride Metro’s bus and rail services and other transit partner systems fare-free.

Some agencies, like the Metropolitan Transit Authority of Harris County (METRO) in Houston, Texas, have conducted zero-fare impact studies that have led to zero-fare implementation being impractical. In METRO’s case, the agency’s comprehensive analysis study showed that removing fares would increase total agency costs despite the predicted increase in ridership. Along with the loss of farebox revenue, additional costs associated with more buses and more operators made the implementation of zero-fare unfeasible [9].

Credit: MTA/Marc A. Hermann

Since a loss of farebox revenue could result in service cuts or serious financial challenges for agencies who are already strapped for cash, fare-capping has arisen as an alternative to zero-fare. For an agency like New York’s Metropolitan Transportation Authority (MTA), whose fare revenues make up a significant amount of their total revenue in a typical year, it is severely challenging to eliminate fares. As a way to incentivize ridership and address cost barriers, NY MTA launched fare-capping through a new contactless payment system called OMNY. The recently launched fare-capping pilot allows MTA users to automatically upgrade to an unlimited weekly pass after paying for 12 OMNY trips with the same device in a calendar week [10].

Key Takeaways from the Mobility Innovation Collaborative

The Mobility Innovation Collaborative (MIC) is a SUMC program supported by the FTA that provides technical assistance and shares lessons learned from innovative mobility projects across the United States to support knowledge exchange and project development. As a part of this initiative, SUMC hosts quarterly conversations with MIC program grantees on key topics relevant to the transit industry. For the January 2022 MIC Quarterly Meeting, SUMC convened a discussion on Zero-Fare with agencies that have piloted or adopted zero-fare transit to better understand what zero-fare means on the ground. Speakers included leaders from four transit agencies: Intercity Transit, DASH, The COMET, and KCATA. Speakers shared their experience discussing zero-fare with their communities, stakeholders, and agencies. Some key takeaways from that conversation include:

“Stair-Step It”

While it may seem enticing to switch to a zero-fare structure right away, some agencies have found that slowly phasing into a zero-fare structure can build a foundation that generates longevity. Rather than jumping straight into a zero-fare structure, Kansas City Area Transportation Authority (KCATA) strategically implemented it over four years, first eliminating user charges for veterans, then high school students, and then at-risk customers before fully transitioning their system. Since partnerships were already formed with community institutions when KCATA embraced a fully zero-fare structure, KCATA was able to leverage these relationships to bring in money that was never there before. This not only helped to sustain zero-fare programming for the long-term, but it brought enhanced local community commitment into its structure.

Be Context-Sensitive

Transition to a zero-fare structure should not occur because it seems like the trendy thing to do. Instead, a transition to zero-fare should stem from assessing specific issues a transit agency or local transit users are experiencing. As Robbie Makinen, KCATA’s CEO, states, “It’s not just zero-fare for zero-fare sake, it is about mixing that into your actual transit plan”. Much of the success and knowledge gained through zero-fare programs is the outcome of agencies thinking long-term about their users’ needs.

Credit: Intercity Transit

For Intercity Transit in Olympia, Washington, going zero-fare was not the initial plan; rather, it emerged as a solution to community-defined priorities the agency was looking to address. The agency realized that changing how fares are paid could have ripple effects throughout the community and tackle current issues like customer confusion, looming budget shortfalls, operator stress, and other system expenses.

The Central Midlands Regional Transit Authority (The COMET) in Columbia, South Carolina originally went zero-fare during the pandemic but ended up reverting to a fare structure after hearing concerns from the public regarding onboard disruptions. Although the zero-fare structure did not work for The COMET, the agency examined other ways to provide for underserved communities and found pass programs were a great way to address mobility barriers while acknowledging community concerns. The COMET partners with institutions that pay a nominal fee and receive free passes for their employees, students, and customers. Since reinstating fares, Director of Marketing, Pamela Bynoe-Reed, noted that The COMET has seen increases in ridership, particularly on their Soda Cap Connector, a circulator route bus service that connects workers and visitors to top attractions in the greater Columbia, SC Downtown.

Innovative partnerships are crucial to addressing some of the issues associated with zero-fare

Partnerships with community players and organizations support transit and make zero-fare possible in many places. Agencies need to be in contact and build relationships with community institutions because of the vital role transit plays in providing access to community services. As some say, “transit is the glue that holds everything together.”

Although zero-fare transit has been shown, in some cases, to increase the number of onboard disruptions from people experiencing homelessness, KCATA has leveraged partnerships with local shelters and advocacy organizations to proactively address onboard disruptions. In combination with requiring individuals to get off the bus after each route cycle, case management teams are put on the agency’s vehicles to offer resources and ensure unhoused individuals are effectively supported.

Frame Transit as Infrastructure

In comparison to other city services, bus service is often viewed differently from other forms of infrastructure. Speakers pointed out that transit is not viewed or treated as a tax-supported benefit like other public services, despite its role in community mobility. Ann Freeman-Manzanares from Intercity Transit noted that “there is a misconception that public transit fares fully support transit’s ability to operate on the ground”, even though fares in many transit systems only make up around 10 percent of revenue. This misconception often stems from transit’s funding structure. Those who travel using public transportation are expected to pay a user fee in addition to supporting it through taxes. Unlike other city services that rely on community investment through taxation, public transit is double taxed. For example, while transit users are met with a fee, car users generally do not have to pay extra to use road infrastructure. When one begins to frame public transit as infrastructure, funding disparities come to light.

Zero-fare Paratransit should be considered, but its impacts are unclear

For DASH, including paratransit service in the transition to zero-fare was straightforward; If paratransit cannot be more than double the cost of fixed-route service, paratransit should be free to users as well. However, as with many agencies, full understanding of the operational and customer impacts of zero-fare paratransit may not occur until later down the line. Intercity Transit, which also eliminated fares among their paratransit services, noted that while it saw paratransit ridership increase 17 percent between January 2018 and January 2020, it was difficult to determine if the increases were due to expanded services or the agency’s zero-fare policy.

Zero-Fare Considerations

As seen, motivations to transition to or maintain a zero-fare structure will often vary depending on the agency. Additionally, eliminating fare collection can result in advantages related to cost, system efficiency, access, and operations. However, it can also present challenges that agencies will need to plan for. Below are agency considerations for zero fares:

Alternative Options

First and foremost, agencies considering changing their fare structure should examine their organization’s capabilities and what needs zero-fare will address on an operational, administrative, and customer service level. While establishing fare pricing levels is tied to revenue, it is also heavily influenced by political and equity concerns. In some cases, agencies may be able to address looming concerns over transit accessibility and equity through alternative fare approaches that don’t require a swift elimination of fares for all system users. Agencies will often undertake fare analysis studies when contemplating changes in fare strategy. The results of these studies provide integral insights and talking points when discussing the feasibility and impact of fare strategy changes among key stakeholders.

When adopting a zero-fare structure, agencies may find it advantageous to take an incremental approach, coordinating zero-fare for targeted groups first. For instance, before transitioning to its one year zero-fare pilot program starting in January 2022, ABQ Ride coordinated with charitable organizations to offer a discounted bus pass program to low-income individuals. By taking a stepped approach to zero-fare, agencies position themselves to build relationships with different stakeholders and strengthen the value of zero-fare over time, all while addressing user needs in real-time. This is particularly noted in KCATA’s work, where the agency partnered with community institutions as they phased in zero-fare for targeted population groups.

Other agencies, like Rockford Mass Transit District (RMTD), have established zero-fares for specific population groups to address current social equity concerns without putting the agency in financial jeopardy. RMTD offers veterans, senior citizens, and students in grades K-12 free rides if they obtain an RMTD Photo ID which can be acquired for a one-time fee.

Funding

Funding will be a key barrier as more cities consider taking on zero-fare programs and initiatives. While not a new concept, going zero-fare has proven difficult for many agencies and thus is not as widespread as it could be because of the lack of transit investment. Funding shortfalls and budget constraints are leading contributors to agencies’ inability to pursue or keep a zero-fare structure. If agencies do not have a plan for making up farebox revenue, going zero-fare can be a problem. Yet, the pandemic has shown that reliance on fare revenue is not a sustainable method to fund transit systems. Consistent and reliable funding streams are needed to support zero-fare programming and keep transit services afloat in the long term.

For DASH in Alexandria, a change in fare policy was made possible by a $1.5 million subsidy increase from the Alexandria City Council and a $7.1 million grant from the Commonwealth of Virginia. However, like with many grants, these are often one-time investments that may not ensure long-term financial sustainability. The $7.1 million grant will support three years of zero-fare service with the commitment that the locality must fund year four on its own. Scenarios like these illuminate the uncertainty of zero-fare in an environment where transit is not prioritized.

Credit: DASH Bus

Community Investment

Zero-fare allows for money previously spent on bus fares to return to the local economy. In Olympia, Washington, a local community college was able to allocate the $150,000-$200,000 investment previously used to provide students with bus passes to assist homeless students with housing, food, and childcare expenses so they could obtain their academic degrees.

Community Collaboration

Zero-fare can reduce a system’s reliance on local, state, or federal funds because it encourages the formation and leveraging of partnerships with community entities. In the zero-fare space, community partners are key contributors. In Mountain Line’s case, the financial support of 14 local organizations and businesses made their initial three-year zero-fare demonstration project possible.

Customer Experience

Agencies should consider how changes in ridership and demand from the implementation of zero-fare will impact other parts of the transit system, its facilities, and staffing needs. Zero-fare can offer passengers a more seamless boarding experience. With no fare collection, riders can bypass the payment process and enter the bus more efficiently, which contributes to lower dwell times and a reduction in fare disputes. Conversely, zero-fare services may attract more riders, which can prompt overcrowding, onboard disruptions, and lead to buses picking up passengers at far more stops. In the case of The COMET, where zero-fare policy was withdrawn out of safety concerns by riders’ request, certain transit routes saw an increase in ridership once fares were reinstated.

Workforce Development

As a part of the efforts to quantify the quality-of-life impacts of KCATA going zero-fare, the UMKC Center for Economic Information (CEI) surveyed nearly 1,700 system users, the majority of which came from working class backgrounds. CEI found that a considerable number of respondents were satisfied with the zero-fare program, with an overwhelming 81.7 percent noting that the ability to ride the bus free helped them obtain or maintain employment [11].

Greater Cleveland Regional Transit Authority (RTA) and The Centers for Families and Children partnered to provide one year of zero fare transit passes for those participating in workforce development programs. Along with the free transit passes, RTA employees provided trip planning training and support to program participants. This initiative was one piece of a larger pilot program to supply the Center’s El Barrio clients with accessible affordable transportation to employment support services such as training or job opportunities. The program arose out of a Paradox Prize Grant opportunity provided through the Fund for Our Economic Future.

Many participants enrolled in the program were able to take second jobs, attend medical appointments, and explore other opportunities. One resident attributed the program to his ability to consistently access his place of employment and subsequently land a pay raise [12]. Prior to the pilot, most residents had to limit their trips due to the cost associated with transit fares.

While quantitative results on the pilot’s success are not yet available, traveler testimonies provide an inside look on how zero-fare transit can contribute to job security, economic stability, and public health. Despite the zero-fare portion of the program ending in October 2021, RTA is assessing alternative pay structures like fare-capping after the pilot affirmed transit affordability is often a barrier to employment accessibility and job sustainability.

Cost Savings

Zero-fare eliminates costs associated with collecting fares and maintaining fare payment processes and equipment. Technological innovation has introduced new payment processes in recent years, yet some transit agencies have found it to be more economical to eliminate fares rather than convert to app-based ticketing systems. Agencies should look to quantify the costs associated with collecting and maintaining fare collection systems.

Fare Payment Integration

Because the nature of zero-fare is the elimination of user fees, zero-fare will have implications on multi-modal fare payment. In places like Montgomery County Maryland, a zero-fare policy halted a pilot project on payment integration via FTA’s Accelerating Innovative Mobility (AIM) program. The pilot project intended to expand fare payment options for riders and create easier transfers between systems in the Washington, DC metropolitan area through the development of a regional electronic fare payment system.

Regional Coordination

When contemplating zero-fare programming, it is important to consider the impacts it may have on a regional level. These may be in the form of challenges or opportunities. Zero-fare systems may not see the full benefit if nearby areas have not adopted zero-fare transit as well.

DASH received pushback from regional partners in their transition to zero-fare because other systems in the area would continue to require fares. Since DASH sees its services overlap with other local transit operators with differing fare policies, there was the possibility customers would be more likely to face confusion or varied levels of transit access.

In areas with overlapping services, DASH saw zero-fare incentivize the use of their services, resulting in ridership loads shifting from the Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority’s regional subway and bus system onto DASH’s local bus system. While increased ridership is often a goal, this shift in load contributed to overcrowding on some routes. DASH was also able to implement all-door boarding on some of their routes, reducing dwell times.

Conclusion

The approach to zero-fare will look different for each transit agency. While zero-fare may not be feasible for all transit systems, agencies who have made it work have found it to be useful to leverage partnerships, improve the perception and ridership of transit services, and help communities as they recover from Covid-19. For those transit agencies that found reinstating fares the best path forward, the zero-fare experience offered an opportunity for agencies to rethink fare collection practices and policy to streamline processes for the benefit of the riding public, as well as their own bottom lines.

The consideration of a zero-fare structure embodies the shift in awareness and motivation surrounding public transit. By going zero-fare, agencies are changing the dialogue and perception of public transit; they are framing transit as public infrastructure which can help its zero-fare sustainability in the long term. Ultimately, zero-fare is not the sole solution to fixing fundamental challenges to public transportation—certainly not its chronic underfunding. But the adoption of zero-fare policies can shift the dialogue and further support a more equitable and accessible transportation system for local and regional communities.

References

- Center for Neighborhood Technology: “The Housing and Transportation Affordability Index”, accessed March 17, 2022. https://htaindex.cnt.org/

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2012. Implementation and Outcomes of Fare-Free Transit Systems. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/22753.

- Ibid

- The Denver Channel: “Chapel Hill offers free transit, cites economic boost”, accessed March 17, 2022. https://www.thedenverchannel.com/news/national-politics/the-race-2020/chapel-hill-offers-free-transit-cites-economic-boost

- National Transit Database: Town of Chapel Hill dba Chapel Hill Transit”, accessed March 17, 2022 https://www.transit.dot.gov/sites/fta.dot.gov/files/transit_agency_profile_doc/2019/40051.pdf

- Brighton McConnell, Chapelboro: “Chapel Hill Transit Marks 20th Anniversary of Free Fare Service”, accessed March 17, 2022. https://chapelboro.com/news/news-transit/chapel-hill-transit-marks-20th-anniversary-of-fare-free-service

- Jenni Bergal, American Planning Association: Can Zero-Fare Transit Work, published October 1, 2021. https://www.planning.org/planning/2021/fall/can-zero-fare-transit-work/#:~:text=In%20Kansas%20City%2C%20Missouri%2C%20transit,Makinen%2C%20the%20transportation%20authority%27s%20CEO

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2012. Implementation and Outcomes of Fare-Free Transit Systems. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/22753.

- Kelly Schafler, Community Impact Newspaper: “METRO board of directors say free fare ‘not feasible’ for transit authority”, published January 16, 2020. https://communityimpact.com/houston/lake-houston-humble-kingwood/transportation/2020/01/16/metro-board-of-directors-say-free-fare-039not-realistic039-for-transit-authority/

- Metropolitan Transportation Authority: “Introducing the weekly farecap with OMNY”, accessed March 17, 2022. https://new.mta.info/fares/omny-fare-capping

- Urban League of Greater Kansas City: ‘ 2021 State of Black Kansas City: Is Equity Enough?’, Accessed March 18, 2022 https://www.google.com/url?q=https://www.ulkc.org/s/2021-SOBKC-Charting-the-Path-Forward-flipbook_PDF.pdf&sa=D&source=docs&ust=1656084069623544&usg=AOvVaw2fOxO9uLCJcnyMpABuZHYj

- Crain’s Cleveland: ‘Transportation pilot makes case for greater fare equity’, Published December 5, 2021 https://www.crainscleveland.com/custom-content-twotomorrows/transportation-pilot-makes-case-greater-fare-equity