History/Background

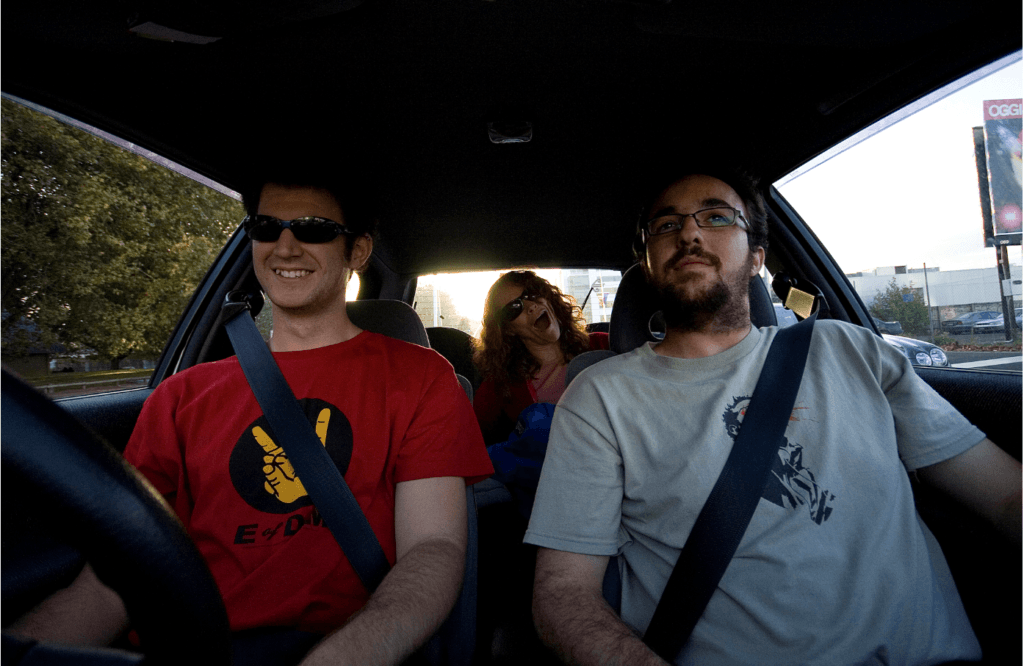

Ridesharing is the grouping of drivers and passengers with common origins and/or destinations into common trips. Carpooling is the oldest form of ridesharing, and can reduce congestion, lower carbon dioxide emissions, and give communities more transportation options. However, the number of people carpooling in the US has decreased since the 1980s. New technology provides an opportunity to revive the practice, with apps aiming to connect drivers and riders in innovative ways.

While rideshare comes in many forms, including vanpooling and slugging, this learning module mostly focuses on app-based carpooling.

Ridesharing has existed since the dawn of the commute. In America, sharing rides to work first became popular during World War II, when the federal government and military encouraged citizens to carpool in order to save rubber and other resources. Workers have historically used a variety of tools to arrange shared rides. In the 1960s, employers took their employees’ information and hand-matched them by geographic area. Popularity again spiked in the 1970s during the oil crisis, due to the expense of gasoline and consciousness over energy conservation. However, starting in the 1980s, these gains were slowly lost as driving became less expensive and two-earner households became more common, making it harder to coordinate trips. In the 1990s and early 2000s, telephone- and Internet-based carpool matching were introduced by cities and municipalities with varying degrees of success. Carpooling apps are the latest technological innovation to be introduced to the sector, beginning with the widespread popularity of smartphones in the late 2000s (a company named Carma claims to be the first, starting in 2008). According to census data from 2019, 8.9 percent of Americans shared rides, or carpooled to work. This number has likely decreased substantially post-COVID-19 pandemic, but as people begin to return to work, ridesharing remains a practical and low-cost alternative to help relieve congestion and mitigate GHG emissions.

Apps like SPLT, Waze, and Scoop mark an evolution from the traditional model of carpooling. Through these apps, users can conveniently plan rides to and from work through their smartphones. Shared rides are formed and scheduled on an ad hoc basis, using GPS to match drivers and riders based on their routes and user preferences.

Next Subsection

Definitions

Traditional Carpooling: Traditional carpooling involves multiple travelers commuting to a shared location using a privately owned vehicle, with the group sharing trip costs and driving responsibilities. Traditionally, carpool arrangements are made through an employer, a carpool agency, or more recently, a public website or social media platform.

App-Based Carpooling: in recent years, phone apps have allowed users to arrange carpool rides on demand. This is different from ride-hailing services in that rather than connecting a passenger to a driver for a transactional trip, these apps connect multiple commuters going in a similar direction. This learning module primarily focuses on this type of carpooling.

Slugging: Casual carpooling or “slugging” is an informal version of carpooling, usually among strangers. Typically, passengers do not pay any money for these rides (or a very small amount to account for trip-related expenses like tolls or gas), and the vehicles are able to use High Occupancy Vehicle (HOV) lanes. Slugging is distinct from traditional carpooling in that riders are most often strangers. Most common in Washington, DC, a driver will pull up to a recognized slug line and announce a destination. Commuters waiting in the slug line will join the driver if they desire to travel to that destination. Since additional passengers allow the driver to use HOV lanes, slugging is beneficial to both parties, and usually no money is exchanged. The informal nature of these trips makes them difficult to track and measure the reduced congestion and GHG impacts, and is not something that a city will likely readily deploy as a planned mobility system.

Vanpooling: Vanpooling is a form of carpooling where a group of usually 5-15 commuters will commute via a larger van, usually sharing driving responsibility. Vans are either owned collectively by the commuters, by a transit agency, or by an employer. Some transit agencies, like PACE in the Chicago, IL suburbs, offer programs that allow groups of commuters to rent a vanpool van on a long-term basis. At least one commuter must volunteer to be the primary driver, and each rider pays a small monthly fee based on distance and number of passengers, which covers fuel, tolls, insurance, and all other vanpool costs.

Previous Subsection