The Transit App and Private Sector MaaS Approaches, 2020

5 minutes Date Launched: Sep 15, 2020 Pilot Project Timeframe: Date published on Learning Center.

Summary

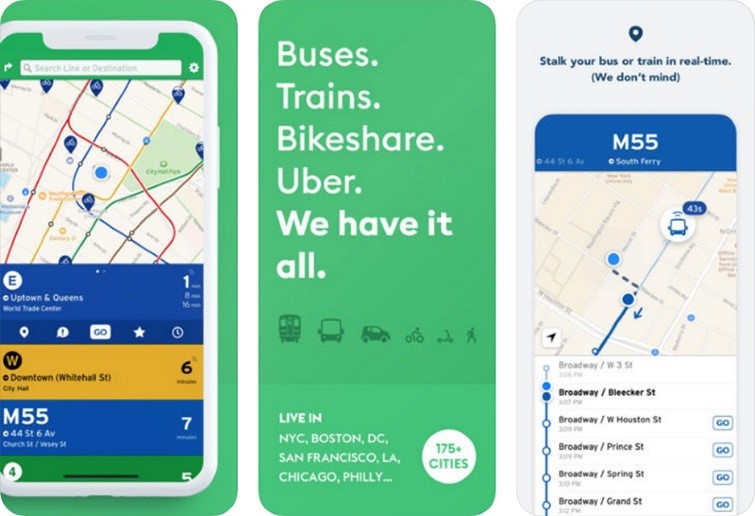

Several travel planning apps with MaaS-like integration functions have been developed recently. An early leader in the space, Moovit, was acquired in May of 2020 by Intel for $900 Million. Citymapper is another. Since launching in 2012, the Transit app, developed by the company of the same name, has grown to be a leading example of MaaS efforts at scale in North America. The company began its journey by partnering with transit agencies to aggregate schedules from multiple agencies, publishing frequency and service information so that a user could navigate the transit system in any participating city. Eventually, they also added the public API feeds from micromobility companies, showing real-time locations of scooters and bikeshare bikes. In 2016, the company introduced payment for many bikeshare systems in partnership with one of the biggest operators, Motivate, clearing a major hurdle towards payment integration. Beginning in 2018, Transit also launched transit fare payments in their app, steadily adding more payment options across North America in partnership with agencies. In multiple cities, they became the “official” transit-planning app, a sometimes informal arrangement in which the agency promotes the app and the app provides a local fare payment option. This has pushed the brand ahead as it has grown to be the transit app for dozens of U.S. cities. By integrating multimodal planning, booking, and payment for single trips, The Transit app stands out as one of the few examples of apps that integrate multimodal planning, booking, and payment for single trips. The Transit app is primarily backed by venture capital, but it receives some funding from the local transit agencies that it partners with directly to integrate ticketing.

Much of the data the Transit app uses is widely available, thanks to public efforts. Part of this integration is due to standardized information feeds. The General Bikeshare Feed Specification (GBFS) used for bikeshare grew from the similar General Transit Feed Specification (GTFS), which was developed through a partnership between Google and Portland’s TriMet to develop a consolidated stream of information from transit agencies to tech companies. In both cases, a standard data reporting format allows third-party apps like the Transit app to display real time information like headways, bike location, or service disruptions..

Because of the public nature of this data, operators like Uber and Lyft have begun offering transit frequency and service information within their own apps. Unlike MaaS principles and platforms that are built on comprehensiveness, these multimodal companies intend to keep riders using their private app exclusively. Critics have referred to this approach as a walled-garden, where many options are available on a single app but only those provided by the app’s parent company. The threat of walled gardens has grown with industry consolidations including major scooter company acquisitions by both Uber and Lyft, and it became apparent when Lyft procured the bikeshare company Motivate and took their data off the publicly available stream. Now, users must use the Lyft app to access bikeshare information for those systems. While the Transit app’s business model is based on the aggregation of services, most mobility companies are focused on volume and exclusivity. The visibility of transit on Uber and Lyft is likely a net gain, but critics question the prospect of a monopoly on multimodalism.