Changing Focus: Mobility Hub Design Centered on Women and Caregivers

20 minutes Author: Natalia Perez-Bobadilla Date Launched/Enacted: Oct 24, 2024 Date Published: October 29, 2024

The Design Framework: Mobility Hubs for Women & Caregivers project identifies the specific mobility needs of women and caregivers and how mobility hubs can be designed to accommodate those needs. It presents a comprehensive guide to reducing emissions, addressing gender-based equity issues, and serving the more vulnerable transportation users.

This write-up describes and analyses the results from a series of dialogues (interviews and focus groups) conducted by the Shared-Use Mobility Center and Living Cities and Communities in collaboration with the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning and key local Community-Based Organizations in Chicago, USA, and Gothenburg, Sweden. These dialogues informed an iterative design process, delivering a Design Framework that will be launched in a Webinar.

A design framework for mobility hubs focused on women and caregivers provides an opportunity to shift priorities in transportation system design.

Introduction

Clara’s car broke down today, putting her in a difficult position. She now has to choose between paying for a ride-hailing service outside her budget or navigating the metro with a toddler, a stroller, and a grocery bag. Both options are so cumbersome that she risks missing her daughter’s doctor’s appointment.

This scenario highlights a broader issue: women face unique transportation challenges and often undertake more caregiving trips than men. However, transportation system designers have traditionally overlooked these concerns.

Women typically make shorter, more frequent trips and are more likely to juggle strollers, bags, and young children. Unfortunately, transit schedules, stations, and facilities that don’t account for these factors result in added costs and delays for women and their dependents (LADOT, 2021; Kauffman et al., 2018; Ceccato, V, 2017; Ortiz Escalante, S. et al., 2021).

A Need for Inclusive Design Frameworks

Recognizing these challenges, the Shared-Use Mobility Center (SUMC) and Living Cities and Communities (LCC) team are developing a Design Framework for Mobility Hubs centered on women and caregivers. This framework prioritizes these groups and introduces seven design principles designers can implement in their projects.

Mobility Hubs offer an innovative solution for creating a robust transportation system while providing users with a convenient place to connect. By shifting the transportation paradigm in these hubs away from the spoke model that caters to regular commuters (mostly men) who travel to their workplaces on a regular schedule during regular work hours, we can make them more inviting for women and foster a sense of community.

The design framework proposed by SUMC and LCC takes transportation access seriously as a critical means of women’s self-determination. It draws on significant studies and feminist geography, linking the concepts of gender, caregiving trips, and structural barriers in transportation (Massey, 1994; Sanchez de Madariaga, 2020; Sheller, 2022).

One of the main findings of this research shows how centering women’s and caregivers’ needs can help increase access to education, employment, healthcare, and other essential quality-of-life options (Berg et al., 2019; Jang et al., 2022) and create a more inclusive and efficient environment for all. This will benefit individuals like Clara and strengthen communities as a whole.

Transportation Challenges Faced by Women

Mobility justice means making transportation fair and equal for everyone. It highlights that mobility isn’t just about getting from one place to another but is tied to various social issues and inequalities. It aims to change the way different forms of transportation are distributed to ensure everyone has fair access.

Research shows that current transportation systems often fail women, especially Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) women. These failures are linked to income, race, ability, and gender.

In 2020, Professor Sánchez de Madariaga talked about the “mobility of care,” which refers to travel related to caregiving tasks. These tasks include activities adults do for children and other dependents, as well as home maintenance. In the U.S., these caregiving activities are mostly done by women, often without pay. For example, in 2016, women made up 75% of caregivers in the U.S., according to the Family and Caregiver Alliance. Globally, over 70% of caregiving work is done by women or girls.

The statistics for paid care workers are similar. Over 80% of paid care workers worldwide are women, but this sector is known for low wages, job vulnerability, and high job insecurity (Zhiyuan et al., 2024).

Despite the significant role of caregiving in society, the transportation needs related to these tasks are often overlooked in policies and research.

Our Research on Improving Mobility for Women and Caregivers

Our international research team from Sweden and the United States explored how cities can design better mobility hubs to serve women and caregivers. We aimed to promote shared mobility as an alternative to private car trips, contributing to sustainable development.

We used a four-step process for our project:

- A desk-based literature review.

- Dialogues with key stakeholders.

- An in-person co-work design workshop.

- The publication of findings is set for December 2024.

Our final goal was to create a set of design principles that would be widely shared through a strategic communication and outreach plan.

To better understand the needs of different groups, we developed personas representing various subgroups of women and caregivers. These personas helped guide our dialogues with stakeholders, including paid and unpaid caregivers, women with disabilities, older women, women of color, and young girls, hoping to create fairer and more inclusive transportation systems for everyone.

| Everyday or Occasional Unpaid Caregiver | Paid Care Worker | Older Woman | Woman with Disabilities | Woman Moving Free and Safe | Child and Young Girl |

| This persona takes on caregiving responsibilities for one or more people without financial compensation. | Professionals providing paid care services. Individuals whose workforce may be composed of young migrants who might not master wayfinding or language. |

Older women with reduced mobility. Women that consider technology doesn’t answer their needs. May have a slower navigation. |

A person with reduced mobility and with functional, sensory and cognitive diversity. | A persona whose use of mobility is a means of self-determination, yet it can be limited due to experienced or perceived gender violence, sexual harassment and other. | A persona that is underage but still needs to move from point A to point B in a small radius safely and feely. Ex. from home to school, a local shop, a mall or an after-school class. |

Dialogues with Key Stakeholders

We contacted community-based organizations (CBOs) that matched the profiles we were looking for. We held eight focus groups and conducted about 13 interviews with 66 women and people of non-conforming gender in Chicago, USA, and Gothenburg, Sweden. Participants’ ages ranged from 11 to 95.

SUMC, with support from the Chicago Metropolitan Agency for Planning (CMAP), led the project in Chicago. In Gothenburg, team members from Living Cities and Communities took charge of the discussions. The community-based organizations we partnered with are:

- Chicago, USA

-

- Northwest Center Belmont Craig, Chicago (NWC)

- Access Living

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), Evanston Chapter

- Equiticity

- Gothenburg, Sweden

- Swedish Lutheran Church in the district of Tynnered, Västra Frölunda

- The district organization Tikitut

- Angered Lövgärdet, Gothenburg

Collaborating with these organizations we gathered valuable insights and perspectives from the community members.

Mobility Patterns and Challenges of Women and Caregivers

Our study looked at how women and caregivers get around, using both numbers and personal stories. We discovered some interesting trends in their transportation habits, popular words they use when talking about travel, and their feelings about their usual travel methods.

Transportation Modes

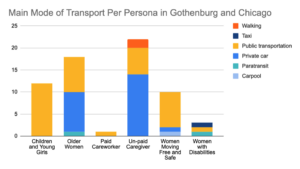

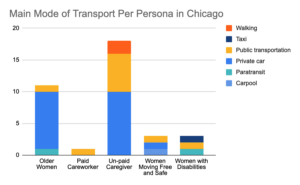

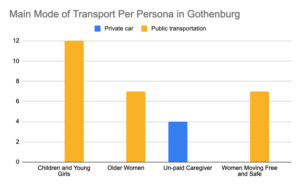

Women and caregivers choose their transportation based on their age and needs. For example, women in Chicago and Gothenburg who take care of children often use private cars more than other women. Younger girls, teenagers, and older women tend to rely on public transportation.

Geographic Differences

Swedish respondents use public transportation more often than those in the US. This might be due to Sweden’s policies that encourage public transit use.

Daily Travel Concerns

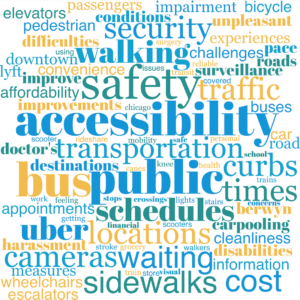

Participants in both Chicago and Gothenburg often think about their daily travel. Interview and focus group prompts fell under five broad themes: accessibility, care, safety, convenience, and costs. We created a word cloud from their responses, revealing that the main concerns revolved around:

- Safety

- Reliability (like waiting times and schedules)

- Traffic

- Accessibility

- Different modes of transportation (such as Uber, Lyft, walking, and biking)

Design Principles

Our interviews and focus groups helped us identify key themes to guide the design of the new mobility hubs. We grouped these findings into seven categories, providing an overview of the different needs and transportation challenges of women and caregivers.

- Personal Security: Many reported feeling unsafe on trains due to drug use, harassment, and lack of security across all types of transportation. Traveling in the evening and at night is particularly concerning, especially in poorly lit areas.

- Convenience: Reliable transportation is very important. In Chicago, unpredictable bus schedules often cause delays and overcrowding. Some noted that a bus trip taking up to 2 hours can be completed in just 50 minutes by car.

- Comfort: Travel comfort is affected by issues like traffic congestion, bad road conditions, and weather. Respondents suggested adding covered bus stops to protect against rain and storms and called for more considerate drivers. In Gothenburg, people desired free toilets, better seating, improved pedestrian crossings, and affordable cafes to make travel more pleasant.

- Care: We talked to 22 caregivers, primarily mothers. Twelve of them mainly use cars, followed by public transit. Many caregivers avoid using baby strollers due to bad street conditions, crowded buses, and a lack of respect for priority seating.

- Accessibility: Physical barriers like poor road and sidewalk conditions, broken escalators and elevators, and issues with Uber and cab services make travel difficult. Paratransit services were praised as a good option for women with limited mobility, but the high costs and delays were concerns.

- Traffic Safety: Participants suggested installing barriers between train platforms and tracks to prevent accidents. They also recommended better pedestrian crossings to improve safety.

- Costs (Affordability): Transportation costs and strategies to manage expenses were discussed. Some women opt for trains or carpooling to save on parking fees, while others find the safety of cars worth the higher gas and parking costs. Women with disabilities often rely on Uber for long distances, which can be expensive. In Sweden, many women use public transit cards provided by schools or the government, and mothers often take advantage of free travel during off-peak hours by car.

Conclusion

In conclusion, designing mobility hubs that prioritize the needs of women and caregivers can improve the hub’s services and increase (multimodal) transportation serving women, caregivers, and other more vulnerable users of transportation systems.

By recognizing women’s unique travel patterns and caregiving responsibilities, SUMC and LCC offer transportation professionals innovative solutions to mobility challenges. As the next step, the project will publish a framework that describes design principles and the potential application of these.

A mobility system that supports women in their daily caregiving tasks enhances access to essential services such as healthcare, education, and employment, ultimately fostering greater inclusivity. This shift in focus—from a one-size-fits-all approach to one that embraces diverse needs—ensures that transportation systems work for everyone.