Rural Transportation

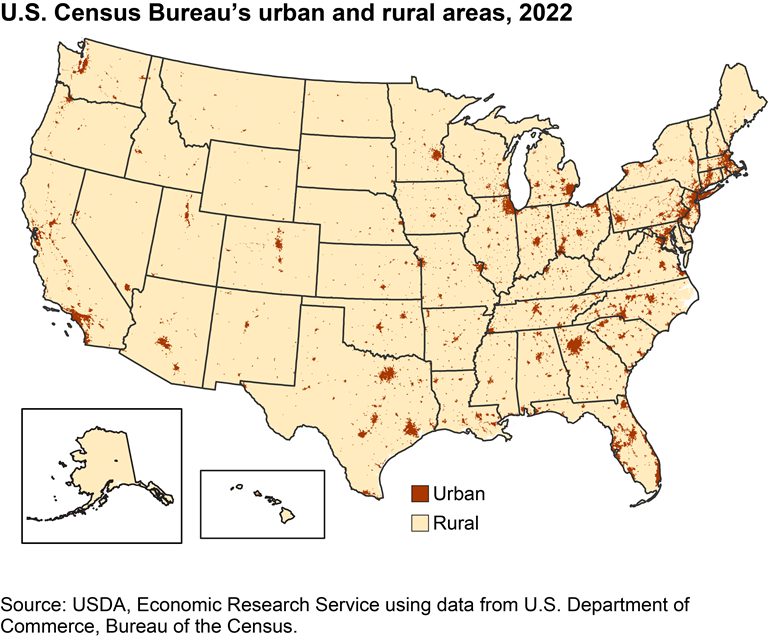

Rural communities make up roughly three quarters of the United States by area, and are characterized by low-density land use and car-oriented infrastructure. Homes, workplaces, schools, and other destinations are often spread across these wide geographic areas, resulting in long travel distances or limited access to public transportation. These conditions have real implications for rural residents: an older adult who no longer drives may face mobility limitations that restrict access to healthcare, grocery stores, and social connections; a middle-aged person with a family may face a “time poverty” effect by the significant amount of time spent driving children, older relatives, or both to various destinations; a teenager who is too young to get a driver’s license may lack the ability to independently travel altogether. The combination of dispersed destinations, car dependence, and limited transit options not only affects daily logistics but also contributes to social isolation, economic strain, and reduced opportunities for engagement in community life. Understanding these human impacts is essential for designing mobility solutions that truly address the needs of rural populations.

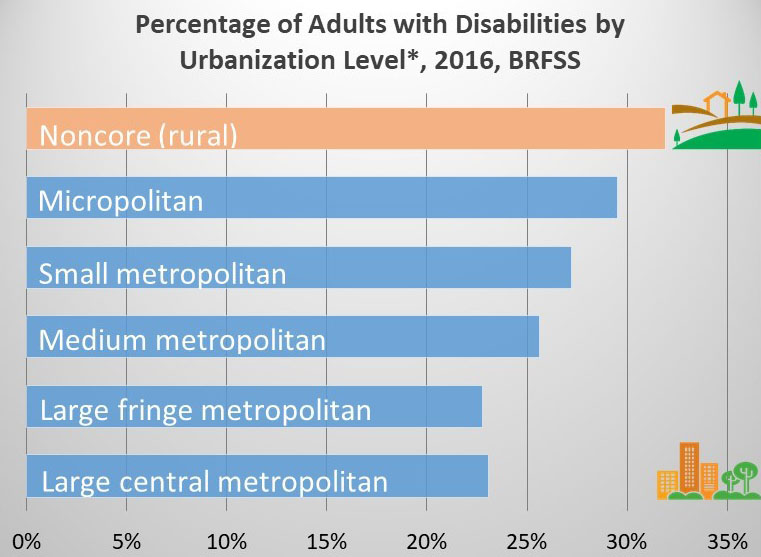

Private cars are often the most common mode of transportation in rural communities. Therefore, dependency on the personal vehicle can be a challenge for rural populations, as they often have a larger aging population than their urban counterparts with residents 65 and older making up 18% of adults in rural areas compared to 13% in urban areas. This is an important consideration for transportation planners, as older adults tend to have greater mobility limitations; for example, one third of 65+ year-olds have a disability that limits mobility. At the same time, rural areas tend to have fewer transportation alternatives: only about 60% of rural counties have any form of public transit service, and many offer limited hours or geographic coverage. As a result, older adults who no longer drive often face reduced access to medical care and greater risk of social isolation, underscoring the need for flexible and community-based mobility options.

While some shared mobility modes like microtransit can help address gaps in rural transit, they are not inherently more affordable operationally. They must be carefully matched to local needs, funding capacity, and operational context. Transportation planners must consider factors such as initial and maintenance costs, effective service model, and community needs or demand. For instance, dial-a-ride may be too costly for one rural community, but can appropriately fulfill the needs of a different rural community.

Next Subsection

Transportation Access

Access to transportation options is crucial for moving residents to, from, and around rural communities for many reasons. While a personal vehicle serves as a suitable option in many rural communities, many residents may not be mentally, physically, or financially able to own or operate one. Ensuring that these populations retain their mobility independence is important for not only the individual but also rural communities as a whole:

- Public transportation is closely linked to job creation, economic growth, and improved quality of life.

- In rural communities, individuals who don’t have access to or can’t operate a personal vehicle are often left with few alternative public transport modes and are isolated from essential services.

Mental health in rural communities is often worse than their urban counterparts, which can be attributed to isolation from activities, friends, and experiences.

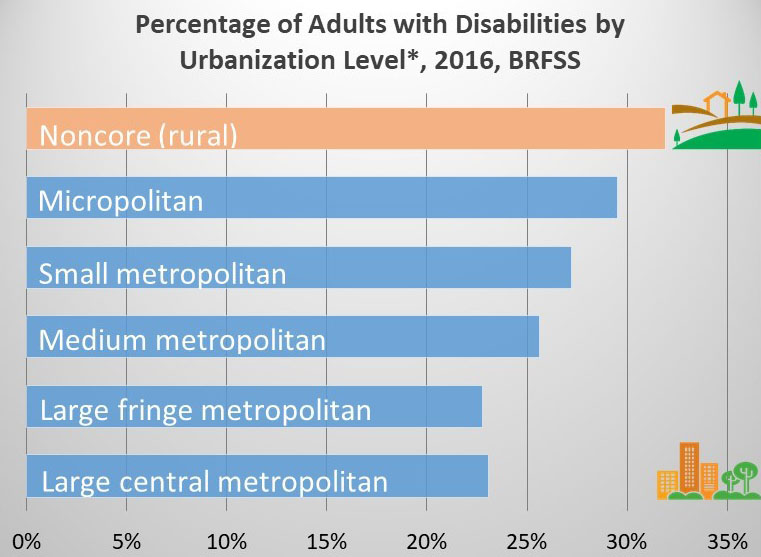

A graph from the Center for Disease Control using data from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS), showing that roughly 33% of adults with disabilities live in rural areas. Credit: CDC

A study of seniors in New Brunswick, Canada, highlights the impact of losing access to a personal vehicle in a rural community. Researchers studied older drivers in rural communities who lost access to a personal vehicle, and found that the group’s number of total trips decreased by 34% over the duration of the study’s time frame. The reduction in individual mobility affects the health and wellness of residents as a result of limited access to essential services, including healthcare, grocery stores, and community centers. Older adults in this study who were unable to drive took 15% fewer trips to the doctor, ultimately putting them at a greater risk of adverse health outcomes due to a lack of preventative or delayed medical care. Gaps in reliable transportation give residents no choice but to seek medical attention in an emergency setting, which can strain emergency services by imposing an over-reliance on emergency departments and ambulance services for non-emergency healthcare.

Previous Subsection Next Subsection

Types of Services

Characteristics of rural landscapes like population density, and land use can make providing reliable and accessible service challenging. Despite this, service providers are creating services tailored to the specific needs of their region and testing creative ways of overcoming these challenges. For example, a permanent fixture such as a bike dock or light rail stop may better fit a dense region, while a demand-responsive transit (DRT) service may be more fitting for a low-density region (for specific details on these services, please visit SUMC’s definitions page). Below are more examples of transportation services that have been used in rural communities.

Microtransit

This service type is being deployed in rural areas and often operates as flexible transit, or a Mobility on-Demand (MOD) service. For more in-depth information about microtransit services, visit SUMC’s Microtransit Learning Module. In rural communities where fixed-route transportation can be scarce, microtransit can be a cost-effective and efficient fit. Microtransit services can be scheduled to specific individual rider origins and destinations within a service zone – rather than designated stops like fixed routes – through mobile apps, online platforms, or a phone call to a call center. Microtransit services that are already implemented across the US have brought significant benefits to rural communities. Firstly, microtransit can reach residents who were previously difficult to serve with traditional fixed-route public transportation. As rural communities are often low-density areas, running fixed-route service can be inefficient and costly for transit agencies, leading to gaps in service and longer wait times for users. In addition, microtransit services in rural communities can have a profound impact. Many residents face barriers to transportation and cannot operate personal vehicles themselves. In rural communities especially, social isolation can be a major challenge due to the lack of nearby services or community hubs. Reliable transportation enables these individuals to reach essential services independently. Finally, microtransit can fill the gap in supporting local economies while reducing social isolation by making it easier for residents to travel to friends, family, religious services, or community events.

- Sussex County, Delaware: DART Connect is Delaware’s first on-demand microtransit service, designed to replace underperforming fixed routes in two rural towns. Launched in 2021, the program uses a mix of cutaway buses and contracted taxis to provide low-cost, app- or call-booked rides with short wait times and high coverage. Uniquely, this program utilizes partnerships with employers like Mountaire Farms to serve shift workers, flexible vehicle types to match demand, and data-informed adjustments to improve reliability in areas with limited broadband access.

- Cecil County, Maryland: Launched in April 2021 through a FTA Integrated Mobility Innovation grant, this targeted pilot by Cecil Transit provides on-demand mobility specifically for residents of addiction recovery houses offering rides to jobs, medical appointments, legal services, and more. This service operates across 71 sq mi area, and uses six minivans and part-time drivers dedicated solely to this service.

- The Grand Gateway Economic Development Association received a Federal Transit Administration Integrated Mobility Innovation grant to develop PICK Transportation, an on-demand microtransit service in the rural and tribal areas of eastern Oklahoma. A consortium of several rural transit agencies and tribal nations participate in the PICK program to provide after-hours on-demand public transportation to rural communities in eastern Oklahoma.

Credit: PICK Transportation

Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT)

NEMT is a specific category of human services transportation that provides patients with trips to medical appointments, return trips from hospital emergency rooms, and transfers between hospitals. These trips are usually not operated by a transit operator and typically leverage Medicaid as a provision, allowing eligible populations (low-income, older adults, or those living with a disability) to receive affordable access to appointments, though the service provision differs by state. These programs are largely supported through 5310 funding with a local match, which usually supports procurement and in some cases, operations. Rider costs are generally low or free depending on the program. The Government Accountability Office produced guidance in the report Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Updated Medicaid Guidance Could Help States to help navigate variations in eligibility by state. Another useful source to learn more about the differing state-by-state policies is the TCRP Project B-44 report.

Other potential partners, such as healthcare organizations and local employers, might be interested in collaboration. There is a growing need for collaboration between local healthcare providers, hospitals, and transportation services, due to the long travel distances to essential care facilities. Below are examples of how healthcare providers, human services agencies, and private and public transportation providers are working together to offer solutions to improve transportation access and mutually address each partner’s goals.

- Shawano and Menominee counties of Wisconsin led a NEMT service through collaboration with members of the Menominee Nation. The program addresses operational barriers and is now relied on by many residents for routine visits, and picking up prescriptions.

- The Bay Area Transportation Authority (BATA) in Traverse City, Michigan launched Link On-Demand, a pilot program combining MOD and NEMT service models to serve rural Tribal Communities. By 2030, these regions hope to hire more drivers and be able to provide service to more medical facilities outside of the current service boundary.

- Feonix Mobility Rising funded a study to develop and evaluate a shared mobility system to improve healthcare access in two underserved communities in Michigan and rural Indiana. The project addressed missed appointments at healthcare facilities in these communities and gained an understanding of effective design strategies for shared mobility systems in urban and rural settings.

- In Pierre, South Dakota, River Cities Public Transit and Avera St. Mary’s Hospital partnered to offer a NEMT service to help reduce missed medical appointments and increase ridership.

Avera and River Cities Public Transit partner to provide NEMT services. Credit: Avera

Rideshare/TNCs

Ridesharing services can provide on-demand trips for the aging population, NEMT riders, veterans, and the general public in these areas. While Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) like Uber or Lyft are available services in some rural communities, independent launches of these ridesharing services are often not economically sustainable because of a limited number of total riders and/or costly trips. Due to these challenges, the successful introduction of ridesharing in these areas often depends on strong partnerships between rural transit agencies and ridesharing providers.

- Non-profit organization UZURV partners with TNCs to help individuals, families, agencies, organizations, non-profits, and communities ensure that everyone in both rural and urban communities has access to reliable and affordable means of transportation. As of 2024, UZURV services more than twenty regions across the US, focusing specifically on paratransit services.

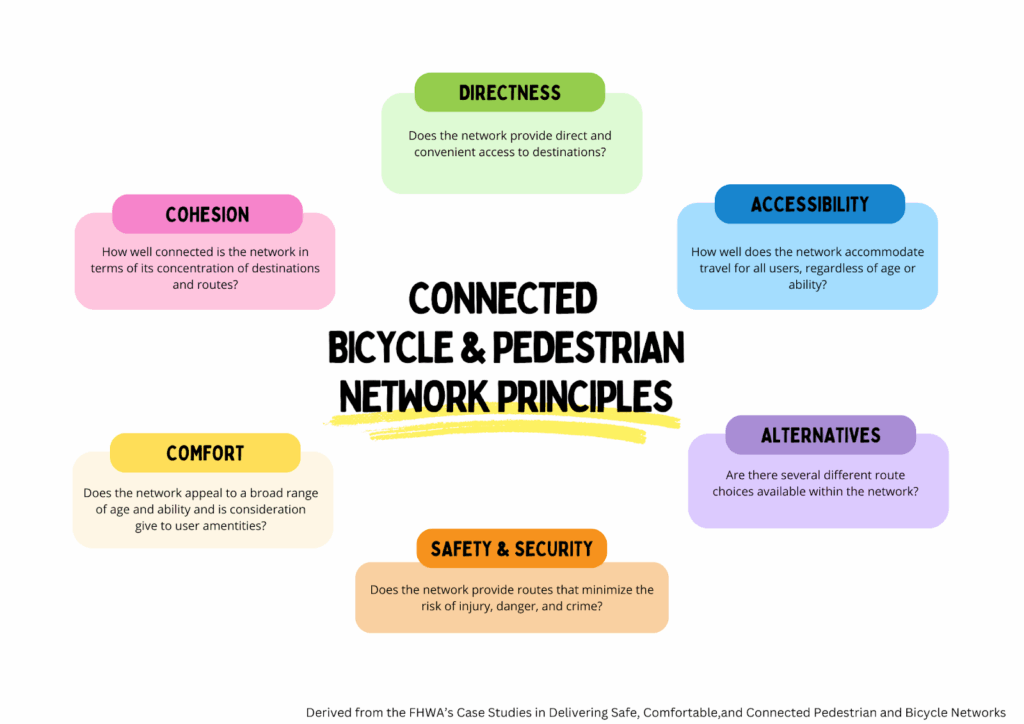

Bikeshare

Bikeshare can be an affordable option that can encourage active transportation in small towns or tribal communities. If it is not already in place, rural communities should plan the supporting infrastructure – bike paths, routes, or signage – vital to achieving safe and successful bikeshare operations. Examples of former and current bikeshare programs in rural and small urban settings include:

- In 2021, the Crawford Area Transportation Authority (CATA) in Meadville, Pennsylvania established a non-profit organization to enhance regional mobility and introduce a bikeshare program in Meadville, a rural community in Northwest Pennsylvania. Given the scarcity of bikeshare models in rural areas, CATA initially faced challenges in securing financial support for this relatively untested concept. However, leveraging its strong community presence, CATA successfully built partnerships to launch the Meadville Bike Share program. CATA adopted a grassroots approach to partnership building, funding, and marketing. The program is funded through sponsorships from various local businesses and marketed via community engagement efforts. Meadville Bikeshare has become a community staple since its 2021 launch, and CATA has expanded the program to other locations in the city, with additional plans to expand to area state parks and nearby Titusville.

- In 2022, the City of Kannapolis, North Carolina partnered with bikeshare operator Tandem mobility to launch KANCycle. KANCycle stands out for its adaptability and emphasis on affordability and access. The program is supported by city leadership and community engagement, and features several station locations across Kannapolis with pricing intentionally kept low to encourage widespread use. KANCycle has been embraced by the community as a tool for recreation as well as first and last-mile connectivity.

Bike Libraries

A bike library model presents an option for rural communities that may not be able to support a traditional docked or dockless bikeshare, as bike libraries do not usually have high start-up costs and are more easily scaled to ridership. In bike library systems, bikes are made available for checkout at places like a local library. In this way, these systems effectively make use of already existing institutions and resources. For example:

- ValloCycle, in Montevallo, Alabama, allows county residents ages 18 and older to rent bikes from city hall or the local university if they are registered members.

- With a grant from Blue Cross Blue Shield of Kansas, Thrive Allen County, a health advocacy organization in Allen County, Kansas, established a free bike library, available to Allen County residents and visitors at nine locations around the county.

Vanpool

Vanpool is a rideshare model where a group of 5 to 15 passengers ride together to a common destination. Vanpool programs may be operated by a public entity, a P3, a private company, or through an employer program. Vanpool programs can operate publicly or privately, but most rely on passenger fares to fund operations.

- Mason Transit Authority (MTA) offers a vanpool program in rural Mason County, Washington, for rural residents. The MTA provides vans and ride-matching services for volunteer drivers.

- California Vanpool Authority (CalVans) provides agricultural workers rides to rural farms. The program offers affordable vans farmworkers can use to drive themselves and others to work. Rides cost around $2, which covers the agency’s maintenance and insurance fees.

- The Florida Department of Transportation (FDOT) Rural Vanpool Program was created from a public-private partnership with COMMUTE with Enterprise, the largest vanpool company in North America. Through the Rural Vanpool Program, COMMUTE with Enterprise will supply up to 40 vehicles to provide vanpool services to counties of critical concern on a month-to-month contract basis. Similarly, the Nebraska Department of Transportation also partners with Enterprise to pilot the Go NEWhere vanpool program. While both transportation options provide vanpool services in rural areas, they have a different focus on who their target riders are. COMMUTE with Enterprise noticed a gap in transportation to employers and work-related trips, while Go NEWhere services riders traveling for personal reasons like healthcare and other social activities.

Carshare

Carsharing services can meet specific needs in rural communities because they offer the option to access goods or services that otherwise are only available for car owners. However, to be effective in rural and small towns, car-sharing services are often small in scale and sometimes subsidized.

- Victor Valley Transit Authority (VVTA) in Victorville, California and Enterprise have shown that carsharing in rural areas is possible by integrating micro-rentals (1-2 hours) for licensed drivers ages 21 and over through the Needles CarShare Program. To keep the program affordable, VVTA offset the usual membership fee and removed the requirement for users to fill the gas tank before returning the vehicles.

- The City of Aspen, Colorado’s Car To Go program demonstrates how municipally-run carsharing can support local mobility needs in small mountain communities, where a diverse fleet of vehicles is necessary to meet the needs of customers. Residents and visitors can rent hybrid or electric vehicles, with the fleet ranging from sedans to SUVs and Trucks.

Volunteer Transportation Organizations

Volunteer Transportation Organizations (VTOs) rely on local volunteer drivers — often seniors, retirees, or part-time workers — to provide rides for community members in need, especially the elderly, individuals with disabilities, and veterans.

While volunteers typically receive mileage reimbursement (often aligned with the IRS rate of 14¢ per mile), this often doesn’t truly cover their fuel, time, vehicle wear, or tax implications. Many VTOs are now advocating for better financial support, including state or federal-level interventions. For example, in Minnesota, the Volunteer Driver Coalition successfully lobbied for legislation that legally distinguishes volunteer drivers from commercial (e.g., Uber/Lyft) drivers, clarifying insurance coverage, and raises reimbursements to the standard business mileage rate, while creating tax breaks so drivers aren’t penalized for excess mileage reimbursement. This addresses a key operational challenge: recruiting and retaining drivers in the face of rising costs, liability concerns, and unsustainable reimbursement models.

VTOs differ from TNCs in several ways;

- Drivers volunteer their time, unlike TNC drivers who are employed by the transportation service.

- VTOs are typically non-profit organizations, rather than for-profit companies. Because VTOs often transport passengers to medical appointments, and because Medicaid has special provisions for NEMT, many VTOs rely heavily on Medicaid for mileage reimbursements. Other operational and organizational costs are often covered through other funding sources, such as grants.

- Passengers requesting a VTO ride usually need to request the ride in advance to ensure the organization can coordinate with an available driver.

For most VTOs, volunteer drivers use their personal vehicle. However, some VTOs have their own vehicle fleet, such as the Green Raiteros program in rural Huron, California. For generations, Huron, California had been home to several Raiteros (or individuals with cars who drive friends and neighbors to their needed destinations). Thanks in part to the advocacy efforts of the mayor and funding from the California Air Resources Board, the town was able to establish the Green Raiteros organization, purchase a dedicated fleet of electric cars, and set up a booking management system. VTO drivers get reimbursed for their expenses on a per-mile basis.

- The Volunteer Transportation Center (VTC) operating in three upstate New York counties has hundreds of volunteer drivers and transports people millions of miles every year. It also provides NEMT and other specialized trips on a limited basis. VTC also developed the data platform, referred to as “VTO in a Box” that streamlines scheduling, tracks ridership patterns, and improves the efficiency of service delivery. The “in the box” solution is a tool that other communities can use to implement their volunteer transportation program.

- The Arrowhead VTO Pilot program experimented with integrating volunteer drivers, traditional transit, and technology for demand-responsive mobility across its ten-county rural service area. The program highlighted challenges in ensuring accessibility that volunteer vehicles typically lacked, such as ease of use for people using wheelchairs. This further prompted efforts to secure funding for accessible supplemental bus service. This pilot operated with a blend of volunteer driver deployment, coordination with fixed-route and dial‑a‑ride services, and efforts to integrate on-demand technologies.

- ITN America’s Volunteer Driver Center (AVDC) is a national initiative to recruit volunteer drivers and connect them with local transportation programs serving older adults and people with mobility challenges. Backed by federal funding, the platform acts as a centralized hub to match volunteers with nearby nonprofits, addressing a key barrier to rural and aging mobility: driver shortages. ITN drivers rarely need to use all of the transportation credits they accrue, so their excess credits go toward ITN America’s Road Scholarship program, which helps low-income seniors access rides regardless of their ability to pay for the service. ITN America also offers a similar program, called the Community Road Scholarship, initiated by small towns and community organizations. When these entities volunteer, their transportation credits are allocated to an account for their residents or members to distribute to in-need populations.

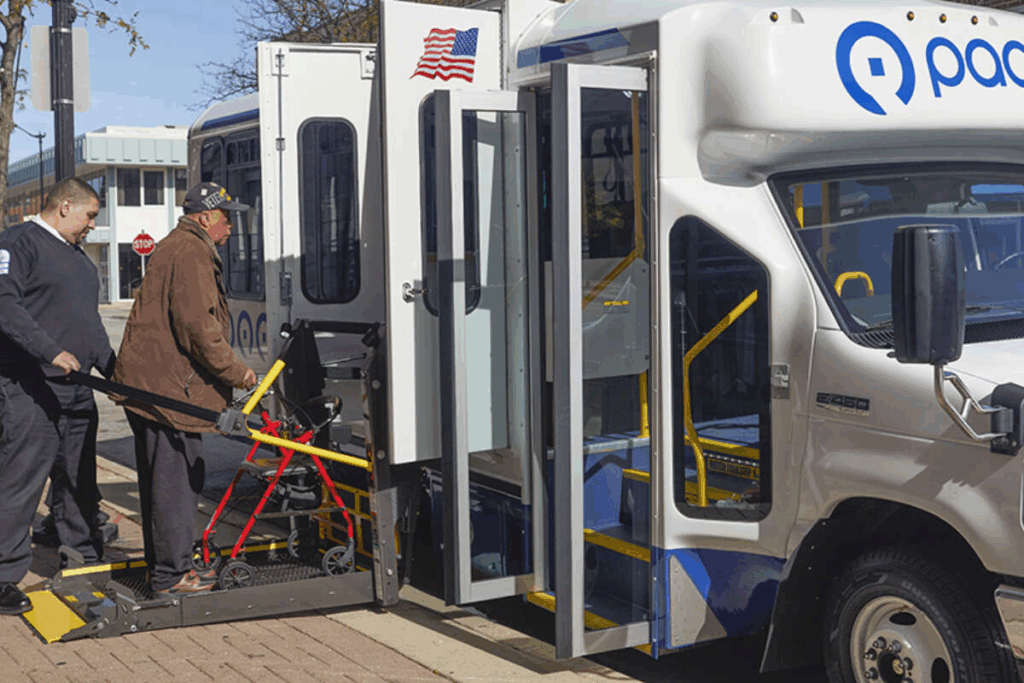

Paratransit

Paratransit is designed specifically for people who may find traditional fixed-route services challenging to navigate or board because of a disability. However, several types of transportation services may fall under that umbrella. In the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), ADA paratransit service is required within ¾-mile of any federally-funded public transit for no more than twice the regular fare, and this service must be available to people whose disabilities prevent them from using any type of public transportation (fixed-route, microtransit, etc.). This may be in addition to the various human services transportation options, such as NEMT services and dial-a-ride services.

Dial-a-ride

Dial-a-ride service is often viewed as a component of paratransit service, as it is a service offered to those who cannot use traditional fixed-route and timetable services like buses and trains. Traditionally, dial-a-ride has been a curb-to-curb service for those with mobility challenges, such as older adults and persons with a physical or cognitive disability. However, in select locations with limited mobility options, dial-a-ride service is open to anyone, including those without mobility challenges. In addition, dial-a-ride can be provided by different organizations, while paratransit is a transit agency-operated service. The service functions much like a taxi, but reservations are needed in advance as hours are limited, and overall operational costs are lower. Many dial-a-ride vehicles are wheelchair accessible.

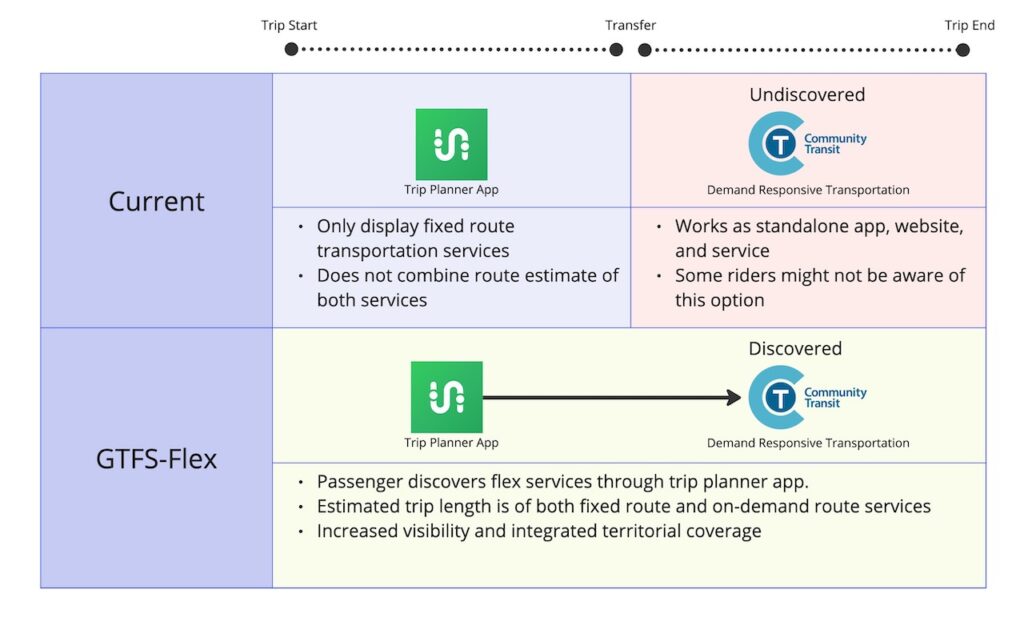

Mobility as a Service (MaaS)

MaaS can integrate multiple transportation services onto a single app or web-based platform. Rural areas characterized by low population density, long travel distances, and low capacity utilization rates of transportation services can use this technology to coordinate different types of transportation to improve efficiency and complete multimodal trips. Users can access wayfinding and trip planning services like ride alerts and trip payment options all in one place. Rural MaaS may focus more on the aggregation of demand due to factors such as population density, demographics, or transportation services available.

- Feonix-Mobility Rising, a non-profit focusing on improving mobility options for under-served and vulnerable populations, is working with the Coastal Bend Center for Independent Living and the Area Agency on Aging to provide mobility options to the elderly and those with disabilities in the Coastal Bend region of Texas.

- Led by the East Central Wisconsin Regional Planning Commission, several Winnebago County entities developed the Winnebago Catch-A-Ride Rural MaaS program through a collaboration with Feonix – Mobility Rising and QRyde. Through this program, all available transportation services in the region are integrated into a single platform.

Previous Subsection