Types of Shared Mobility

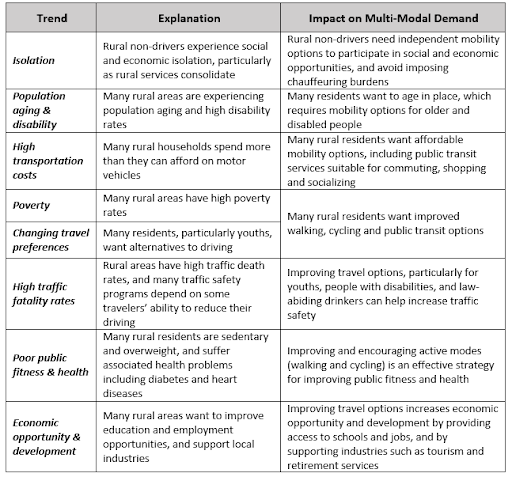

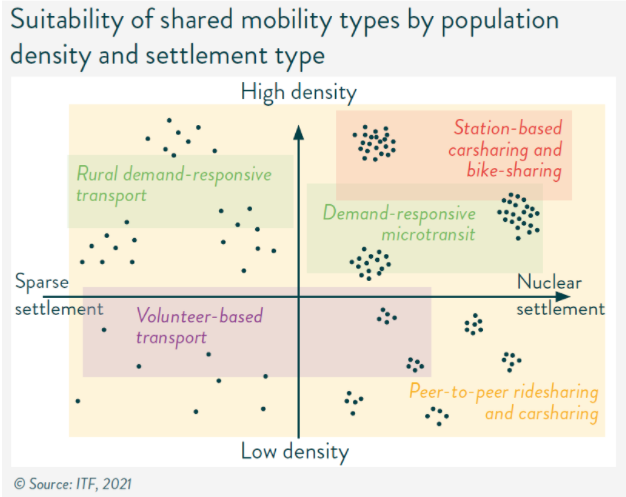

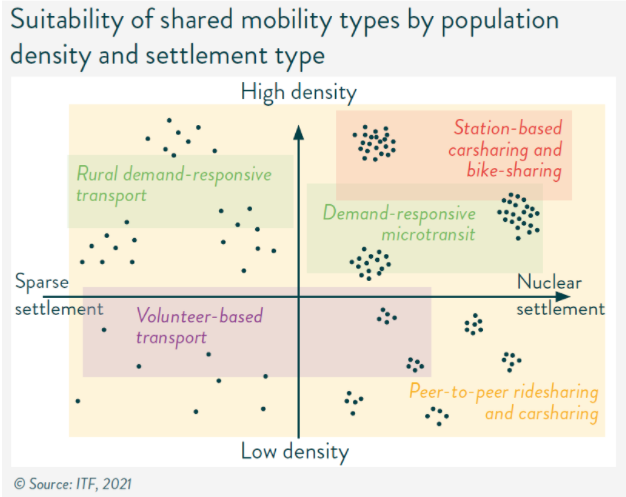

Descriptions of the different types of transportation services found in rural areas are located below. Population density and land-use can often provide an overview of the geographic contexts in which different types of services are best suited.

Microtransit: Microtransit can refer to on-demand transportation, demand-response transportation, flexible transit, or mobility on-demand. Recently, rural and small towns are utilizing microtransit to expand mobility options for their residents. In these less dense areas, microtransit on-demand zones offer a way to reach previously inaccessible residents in the transit system. Microtransit has replaced fixed-route service in rural areas, or traditional demand response services have transitioned to the use of microtransit applications.

Rideshare/TNCs: Ridesharing services can provide on-demand trips for the aging population, NEMT recipients, veterans, and the general public in rural or small towns. While Transportation Network Companies (TNCs) like Uber have brought services to some rural and small towns, independent launches of these ridesharing services are not sustainable because of limited riders or costly trips. Due to these challenges, successful integration of ridesharing in rural and small towns depends on partnerships between rural transit agencies and ridesharing providers.

Bikeshare: Bikesharing services are affordable options that can encourage active transportation in rural communities. However, there needs to be infrastructure, such as bike paths, routes, or signs, to achieve safe and successful bikeshare operations. If the necessary infrastructure is not in place, implementation of these facilities would need consideration ahead of planning for operations. In rural areas, bikeshare and scooter share programs are typically owned and operated by non-profit organizations or local jurisdictions. Low-cost bikesharing systems like the library model are best-case scenarios for rural communities as they do not have high start-up costs or require a set amount of ridership. In library model systems, bikes are made available for free checkout at places like the local library and effectively make use of already-existing institutions and resources. For example, the town of Montevallo, Alabama, uses a bike library model program called ValloCycle where residents ages 18 and older can rent bikes from city hall if they are registered members.

Carpool/Vanpool: Vanpool is another rideshare model used by rural residents where a group of 5 to 15 passengers ride together to a common destination. Vanpools programs found in rural areas may be operated by a public entity, a public-private partnership, private companies, or an employer program. Most programs rely on passenger fares to fund operations but can operate publicly or privately. In rural Mason County, Washington, Mason Transit Authority (MTA), offers a vanpool program for rural residents where they provide the vans and ride-matching services, but rely on volunteer drivers for actual operation.

Carshare: Carsharing services can meet specific needs in rural communities because they offer the option to access goods or services for a short period of time. However, to be successful in rural and small towns, carsharing services must often be small-scale and subsidized. Victor Valley Transit Authority (VVTA) and Enterprise have shown that carsharing in rural areas is possible by integrating a program that offers micro-rentals (1-2 hours) for licensed drivers ages 21+. To keep the program affordable, VVTA offsets the usual membership fee and does not require users to fill up the gas tank before returning the vehicles.

Volunteer Transportation Organization: Volunteer Transportation Organizations (VTO) are organizations that manage and provide rides voluntarily. Traditionally, they are comprised of local drivers transporting local passengers, and predominantly serve populations with mobility challenges, such as the elderly, people with disabilities, and veterans. VTOs can range in size, with some requiring complex driver managing practices, specialized booking software, and 24-hour call-in centers. For example, the Volunteer Transportation Center in upstate New York, operates in three New York counties, has hundreds of volunteer drivers, and transports people millions of miles each year. It also serves both medical trips and other types of trips on a limited basis.

In most VTOs, volunteer drivers use their personal vehicles to drive people who have requested a ride to and from their destination; however, some VTOs own their vehicles, such as the Green Raiteros program in rural Huron, California. For generations, Huron, California had been home to several Raiteros (or individuals with cars who drive friends and neighbors to their needed destinations). However, thanks in part to the advocacy efforts of the local mayor and funding from the California Public Utilities Commission, the town was able to establish the Green Raiteros organization, purchase dedicated cars, and set up a booking management system. VTO drivers get reimbursed for their operational expenses on a per-mile basis.

VTOs differ from TNCs in several ways; first, the drivers are volunteering their time, unlike TNC drivers who are employed. Second, VTOs are typically non-profit organizations, rather than for-profit companies. Third, because VTOs often transport passengers to medical appointments, and because Medicaid has special provisions for non-emergency medical transportation, many VTOs rely heavily on Medicaid for mileage reimbursements. Other operational and organizational costs are often covered through other funding sources, such as grants. Finally, passengers requesting a VTO ride usually need to request the ride in advance to ensure the organization can coordinate with an available driver.

Paratransit: Paratransit is typically regarded as a transportation service for people who cannot use traditional fixed-route services. However, several types of transportation services fall under that umbrella. For example, in the 1990 Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), ADA paratransit service is required within 3/4 mile of any federally-funded public transit for no more than twice the regular fare, and this service must be available to people whose disabilities prevent them from using fixed-route service. Additionally, there are human services transportation, such as non-emergency medical transportation services and dial-a-ride services.

- Dial-a-ride: Dial-a-ride service is often viewed as a component of paratransit service, as it is a service offered to those who cannot use traditional fixed-route and timetable services like buses and trains. Traditionally, dial-a-ride has been a curb-to-curb service for those with mobility challenges, such as the elderly and people with disabilities. However, in some locations with limited mobility options, dial-a-ride service is open to anyone, including those without mobility challenges. In addition, dial-a-ride can be provided by different organizations, while paratransit is a transit agency service. The service functions much like a taxi, but reservations are needed in advance, and costs are lower. Many dial-a-ride vehicles are wheelchair accessible.

- Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Non-Emergency Medical Transportation (NEMT) is a specific category of human services transportation that provides patients trips to medical appointments, return trips from hospital emergency rooms, and transfers between hospitals. Medicaid has a provision for NEMT allowing those who are low income, older, or disabled to receive affordable access to appointments, though the service provision differs by state. The Government Accountability Office produced guidance in the report Non-Emergency Medical Transportation: Updated Medicaid Guidance Could Help States to help navigate variations in eligibility by state. Another useful source to learn more about the differing state-by-state policies is the TCRP Project B-44 report.

Rural Mobility as a Service (MaaS) can integrate existing rural transportations services with existing shared-mobility onto one app-or-web-based platform. Rural areas characterized by low population density, long travel distances, and low capacity utilization rates of transportation services could integrate different types of transportation to improve efficiency. Users can then access wayfinding and trip planning services (ex. receive ride alerts, trip payment, etc.) all in one place. Rural MaaS may focus more on the aggregation of demand due to factors such as population density, demographics, or transportation services available.

Previous Subsection Next Subsection